It is April 19th, 1944. Thousands of mourners silently march from a service at the Warsaw synagogue on Rivington Street to City Hall. A few carry signs: “Save Those Jews in Poland Who Can Yet Be Saved!” and, “Three Million Polish Jews Have Been Murdered By the Nazis!” When they arrive at the steps of City Hall, Cantor Moishe Oysher sings El Mole Rachamim, a funeral prayer for the the 40,000 Jews who died a year earlier in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

The Chief Rabbi of Vilna and former Polish Senator, Isaac Rubinstein tells the crowd of mourners and those listening over WNYC, “A year ago, the remnant of what had been the greatest Jewish community in Europe decided to offer armed resistance to the brutal German murderers.”

Warsaw, the capitol of Poland, had been the home of nearly half a million Jews, about one third of its residents. When the Germans invaded Poland in September, 1939 and occupied Warsaw, they forced all Jews into a crowded ghetto. Eight-foot-high walls topped with broken glass and barbed wire closed off the inhabitants. Within a few years, starvation and deportations to slave labor and concentration camps reduced the number of Jews in Warsaw by more than ninety percent. After meeting with unexpected resistance from ghetto fighters, on the eve of Passover 1943, the Nazis attacked. Rabbi Rubinstein said, “Against heavy odds, they resolved to fight. Not in defense of their lives, for there was no chance to win the battle. It was harder to save the dignity of their people and to wake the conscience of humanity.”

Jews in the Ghetto fought the Nazis with home-made bombs made with broken light bulbs and nails. In a 1993 interview partisan and survivor Vladka Mead said, “My assignment was to try to obtain, in any possible way, arms for the fighters’ organizations… buying dynamite.. smuggling out all kinds of jewelry and selling it to buy the things that were necessary for the primitive factories making Molotov cocktails.”[1] Senator Rubenstein put it this way, “For 42 days and nights, all the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto — men, women and children, old and young, fought almost with naked fists.”The Nazis systematically burned or blew up the ghetto block by block, building by building. Within a month and a half the entire ghetto was razed to the ground.

The 1944 gathering at City Hall Park was not only a memorial for the dead but also a call to action for those still alive. The war was not over and the death camps were still in full operation. Dr. Joseph Thon, head of the General Zionist Organization of Poland and former Editor of the Polish daily Chwila of Lwow, pleaded for support. “Mr. Mayor, at this moment we stand before you as mourners and with hearts full of pain. In our desperation we ask your voice to be heard…Mr. Mayor, help us bring our message to places where the fate of our surviving brothers and sisters may be decided. Help us save them! Chaim Yisrael Chai! The folk of Israel will live forever!”

From his chair on the podium, Mayor La Guardia may have heard these cries for help more acutely than the crowd knew. Mayor La Guardia’s mother was Jewish, and his biographer Thomas Kessner writes that, “although La Guardia did not think of himself as a Jew, his estranged sister was in Europe and he was aware that she had been taken away by the Nazis.”[2] The Mayor calls the event “one of the most impressive ceremonies that has ever taken place at this historic spot…”Every man and woman here assembled is mourning the death of some dear one who was brutally and cruelly murdered by the armed forces of the Nazi government.”

Warsaw Ghetto photo from Jürgen Stroop Report to Heinrich Himmler, May 1943. The original German caption reads: “Forcibly pulled out of dug-outs”. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum via Wikimedia Commons)

Confirmed reports about the extermination camps had reached the public as early as November 1942. CBS correspondent Edward R. Murrow read this copy over the air only a month later. “What is happening is this: Millions of human beings, most of them Jews, are being gathered up with ruthless efficiency and murdered… Since the middle of July, these deportations from the Warsaw ghetto have been going on. Those who survived the journey were dumped out at one of three camps, where they were killed. The Jews are being systematically exterminated throughout all Poland… The phrase ‘concentration camps’ is obsolete, as out of date as ‘economic sanctions’ or ‘non-recognition.’ It is now possible to speak only of extermination camps.”[3]

Mayor La Guardia told his audience of survivors and mourners their voices would be heard. “The American people understand the plight of the people of Jewish faith in Europe. The need to go to their rescue is high on the list of the military actions that are to take place before long.”

Although the Mayor was optimistic, little changed. On the home front, U.S. immigration laws were so zealously enforced that even official quotas for Jews were not filled. Many who were turned away were sent to concentration camps. Long after the war ended, crowds continued to attend memorials in the hopes of finding friends and family they had lost.

It was a day of tributes and remembrance in New York City. In addition to City Hall, the Jewish partisans of Warsaw were also celebrated at a mass meeting at Carnegie Hall, and around the city (except war plants) by Jewish workers who stopped what they there doing for a two-minute silent prayer at 11 a.m. followed by eight minutes recalling the actions of those resisting the Nazis.[4]

[5]

From the Perspective of the Forverts

by Chana Pollack

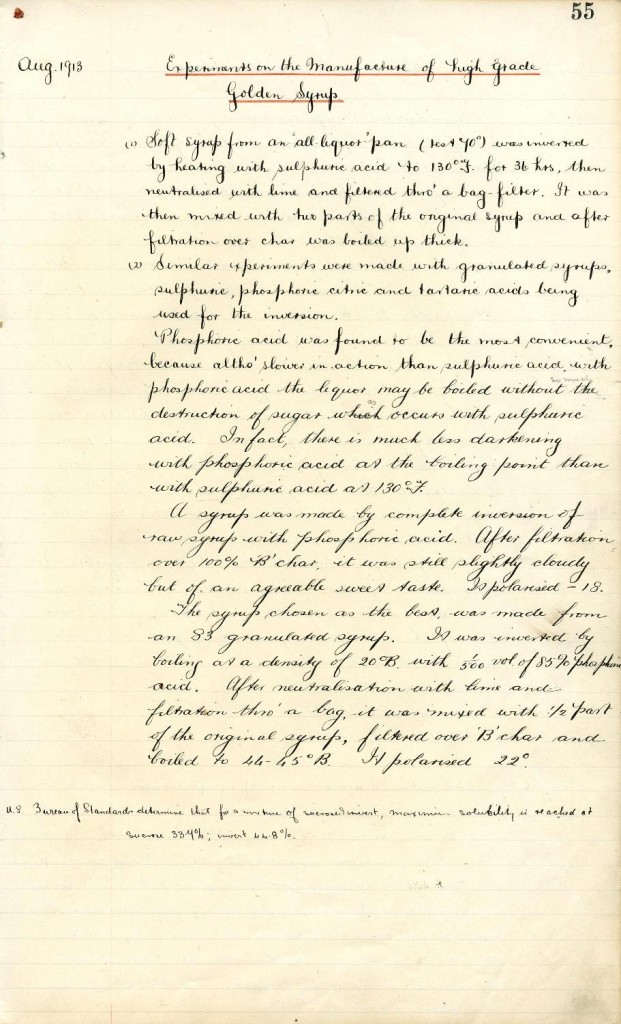

On April 20, 1944 the Forverts edition ran 8 pages for your four cents. As might be expected, headlines followed the war abroad —6,500 airplanes were having an acute effect—Sebastopol was burning and there were counterattacks in Galicia.

Beneath the banner headline, in smaller print, but still bolded, was news from closer to home—hundreds of thousands of New York’s Jews honored Polish Jewish heroes and martyrs—keening in the Warsaw Synagogue and on the streets.

Though aimed at describing the scene on New York’s Rivington Street where the memorial demonstration began at the Warsaw Synagogue, the Forverts delivered uplifting news of spontaneous uprisings in ghettos of leading Eastern European cities such as Vilnius, Bialystok, Lodz, Lemberg/Lwow and additional sites throughout Poland, doubtless inspired by the Warsaw ghetto uprising one year prior.

The Forverts remarked that folks had already gathered hours before this image featuring prominent figures addressing the memorial on a WNYC mic was even taken. The synagogue, they reported, was beyond capacity with over 2,500 people. 10,000 more were estimated to be standing out there attempting to gain access to the synagogue’s interior, in order to honor the Warsaw ghetto heroes.

Far from detailing the celebrated camera ready folks seen alongside his honor, Mayor La Guardia, Forverts reporters wrote viscerally of the neighborhood chronicling scenes inside the synagogue—on the street before it and in shops and factories across the city. The energy of which propelled the historic march to City Hall.

Inside the Warsaw Synagogue the Watenberg family sat with their two recently rescued daughters having had the fortune to arrive to New York City on the ‘Gripsholm’ ship straight from Nazi occupied Europe. The significance of the occasion wasn’t lost on the working folk gathered on the sidewalks of the Lower East Side pressing to be a part of it. From beyond the barricades, the Forverts recalled the sounds of unrestrained weeping never before heard both inside and outside the locale.

At 11 a.m. when the speeches ceased the entire gathering bowed their heads for two minutes of silence, and the Forverts recorded faces inscribed with a deep grief. And those were the faces chosen for the front page diptych to underscore the headlines. New York’s finest (Gentile) policemen were said to have been similarly affected and stood wiping their tear filled eyes.

Acclaimed Yiddish theatre composer Joseph Rumshinsky accompanied everyone’s darling Cantor Moyshe Osher on a pump organ as the El Mole Rakhomim [Lord Full Of Mercy] prayer was intoned for the dead. A member of the crowd rose up and spontaneously recited the Kadish [Mourner’s Prayer]—and again, the entire crowd irrupted in tears.

Before leaving Rivington Street a slight challenge could be heard from the crowd, when controversial Yiddish writer Sholem Asch attempted to speak of faith. Known for his Christological novels, and a rumored conversion, those gathered were seemingly unsettled by Asch’s declaration that God will avenge the Jewish blood spilt. Individuals in the crowd challenged Asch demanding he tell them where god’s son was currently? Was he also going to help them? Who invited him here?— was heard from the audience. Though immortalized in the event’s official photographs, standing next to Julian Tuwim, Poland’s Jewish poet of great renown, organizers later clarified to the Forverts that nobody had in fact invited him.

The entire gathering then formed a long impressive entourage making its way to City Hall. Thousands of Jews en masse walked the streets silently with heads cast down in anguish. At the head of the demonstration was the Watenberg family carrying an American flag.

Placards were carried saying The Ghetto Heroes Blood Cries Out For Revenge! and Three Million Jews Murdered By Nazis—Help Save The Surviving Ones! Thousands stood on the sidewalks watching the Jewish demonstration pass. They could be seen, the Forverts wrote, asking each other about it and listening to explanations.

Despite being unable to attend the march due to work constraints, 4000 shops participated in a work stoppage that day, and an estimated half a million workers honored the memory of their fallen brethren. The Forverts reported that cloakmakers and dressmakers, furriers and tailors, grocery clerks and painters, pocketbook makers, millinery workers and workers in dozens of other fields stopped the wheels of production for 10 minutes as a memorial to those heroic individuals who with their bare hands, led an uprising against the Nazi murder machine.

By evening, thousands attended a concluding memorial event at Carnegie Hall People in the trades, and shops came straight from work to honor the martyrs of the Polish ghetto expressing their desperation at saving what remained of European Jewry. Also not seen in the officially recorded image at City Hall, was Yiddish poet H. Leyvik who that night, read a piece created especially in memory of the heroic uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto.

When listening to the WNYC recording of the day’s events, one easily absorbs the depth of New York’s willingness to acknowledge the unique historic significance of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Reading the Forverts’s accounts of the crowd’s participation helps turn the camera around to observe the people participating in history as they created it. By 1947, only three years after the war, their unflagging energy led to the formation of a memorial plaque at Riverside Drive and 83rd Street.

On October 19th of that year, the Forverts was still 8 pages but had gone up a penny in price and cost you five cents. More than 15,000 people attended the unveiling lasting over three hours in the pouring rain. The Forverts reported it as one of the most extraordinary Jewish ceremonies New York had ever witnessed.

Mayor O’Dwyer was in attendance as were Senator Robert Wagner and several European ambassadors. Cardinal Spellman sent a representative and Manhattan’s Borough President was there too. Cantor Moyshe Osher sang the national anthem while Cantor Moshe Koussevitzky, himself a recent refugee from Warsaw, sang the El Mole Rakhomim prayer. No photos accompany the reporting of that day.

____

[1] Mead, Vladka interview conducted by Andy Lanset, March 15, 1993.

[2] Kessner, Thomas, Fiorello H. La Guardia and the Making of Modern New York, McGraw-Hill, 1989, pg. 525.

[3] Murrow, Edward R., In Search of Light: The Broadcasts of Edward R. Murrow, 1938-1961, Knopf, 1967, pg. 56.

[4] “Jews Here Acclaim Heroes of Warsaw,” The New York Times, April 20, 1944, pg. 10.

[5] This feature piece was originally broadcast on WNYC, April 19, 2001.