The WNYC American Music Festival played a significant role in promoting American music of every genre and provided a forum for new American composers to get their works heard. Conceived in 1939, the festival began in 1940 and continued for nearly 50 years ending up as a day-long series of concerts called WNYC’s Americathon. Although it was no longer as many as 150 special broadcasts[1] during an eleven day period in February, the station continued to broadcast music by American composers and performers from Lincoln’s to Washington’s Birthday.

This celebration of American music and composers came about at a time of uncertainty at home when much of Europe had succumbed to the brutality of Nazi Germany. As a product of the then city-owned radio station, the American Music Festival was considered one of New York’s responses to “Hitlerian destructiveness and fanaticism.” It was meant to be seen “as an expression of a democracy in terms of human fellowship and [the] cultivation of beauty which constitute the final answer to the tyrannies and stupidity of fascism.”[2] The festival was also a response to an overwhelming cultural presence of European classical music on the airwaves at the time whenever classical music was broadcast. On the eve of the first series of forty concerts Station Director Morris Novik said, “American broadcasters have done a splendid job in developing an appreciation of classical music. Radio must do still another important job by focusing attention on American music, and by demonstrating that Americans have written good –even great—music.”[3]

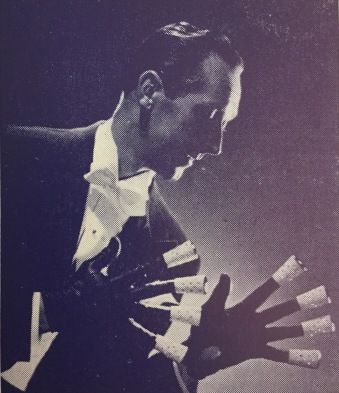

It was an auspicious beginning for the music festival that set the tone and style for many years to come. This first concert series in 1940 heard from the works of Deems Taylor, Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Oscar Levant, Morton Gould and Henry Brant. It included some broadcast premieres such as Brant’s Great American Goof suite and Robert Elmore’s tone poem, Valley Forge, 1777 as well as new compositions by Dante Fiorello, Randall Thompson, Wallingford Riegger and other composers. The audio at the head of this article is the only surviving recording from that first festival in February 1940. It features composer and comedian Oscar Levant at the concluding concert program. In a brief interview beforehand, he comments on the festival and WNYC.

This past week…thanks to the virtually humanitarian auspices of station WNYC, has been dedicated to the performances of contemporary American composers. Performances of modern American composers are about as frequent as social communion with a leper colony. These sparse performances are often accompanied by the same dread of contamination. So, beware!

There are often problems with any endeavor the first time around, and there no doubt was some need to ‘work out a few bugs’ before embarking on the next series of concerts.

The Lester Young Band at performing at Manhattan Center for the WNYC American Music Festival, February 15, 1941.

(Photo by Harry Rubinstein and courtesy of La Guardia-Wagner Archives CCNY)

Indeed, the WNYC producers returned in 1941 with a substantially larger schedule of concerts and, with added broadcast publicity as well as word of mouth, were instrumental in mobilizing some 5,000 people seeking tickets to the opening concert at Hunter College. Some 2,000 were reportedly turned away that Lincoln’s birthday because there was no room for them.[4] That first concert included Deems Taylor’s, The Highwayman in which Richard Hale sang the baritone role and the Manhattan Chorus, the choral part. Also performing folk songs were Pete Seeger, Lee Hayes and Andrew Rowen Summers, as well as jazz from the Benny Goodman Sextet and The Lester Young Band. At the intermission of the final concert for that second festival year composer Aaron Copland was quite pleased with the outcome.

…As a composer, I feel that the more American music is played, the sooner we will create an important music of our own in this country. This festival, it seems to me, demonstrates, at least two things. One- it shows our composers are writing more music than ever before; that they are more active, creatively, than ever before. And secondly, I think it shows that they are not being performed to the extent that they should be performed…Because the radio public, not having to pay anything for admission to a hall, being able to turn off the radio whenever whatever they hear doesn’t please them, that radio public holds for us, I think, our future American audiences. In closing all I can say is, I hope for bigger and better WNYC festivals in the future…

Third annual WNYC American Music Festival ticket from 1942.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

By February 1942, the United States was still reeling from the shock of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor two months earlier, so it is no surprise that evidence of the festival lacks for that year. Based on the paucity of available information one can only guess that WNYC management and staff were under a lot of pressure at that moment to deal with immediate issues concerning the war and to cut back on some of their festival plans despite its patriotic nature.[5] The following year, however, 97 live festival broadcasts were made.[6]

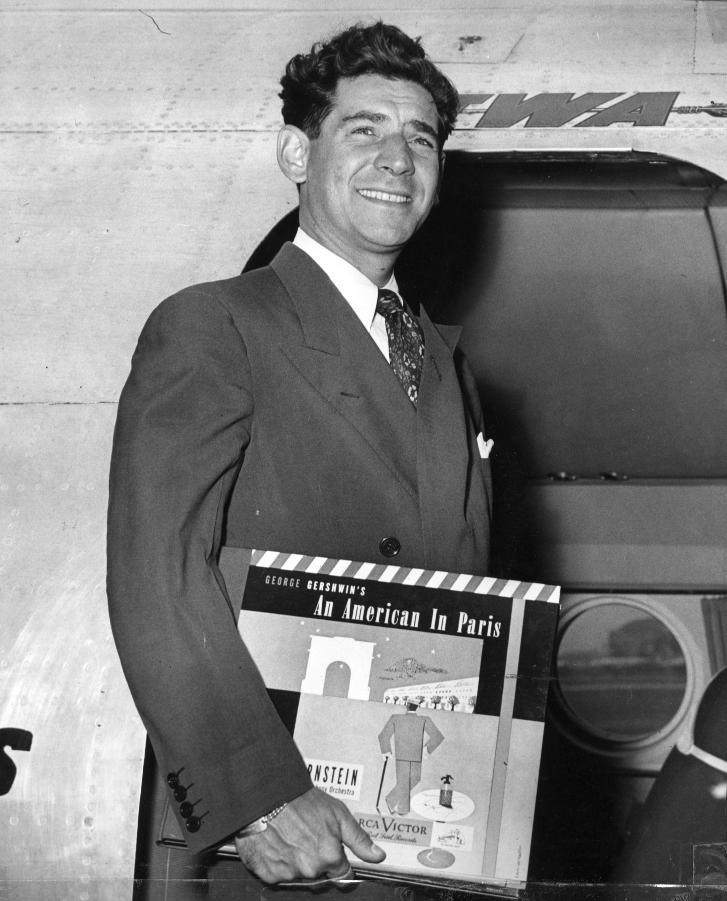

In reviewing the first five years of the festival in 1944, The New York Times reported that WNYC had accomplished one of its main goals with the festival since it was now “an established institution in the city’s musical life.”[7] ASCAP, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers got involved, and the festival program read like a Who’s Who of American symphony, opera, jazz and folk music. Included were Leonard Bernstein, Paul Bowles, Aaron Copland, Sidney Foster, Robert McBride, Paul Nordoff, Vera Brodsky, Virgil Thomson, Henry Cowell, Josh White, Leadbelly and Alan Lomax, Tony Kraber, Richard Dyer-Bennet, Burl Ives and “other exponents of folk and hill music.”[8] 1944 also brought an engineering advance for the festival since it was the first year the music was heard over the “noise-free” frequency modulation (FM) station W39NY. With the end of the war in Europe approaching, the 1945 festival featured a swing-classical combo with Tommy Dorsey teaming up with Maestro Leopold Stokowski making the jitterbugs go wild.

American Music Festival WNYC logo 1940s and 50s.

(WNYC Archives)

After World War II there was a change in management at WNYC as Director Morris Novik went out with Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia and Seymour N. Siegel came in with Mayor William O’Dwyer. Siegel had long been with the station, and no doubt wanted to continue with something that brought nothing but praise to the broadcaster. Indeed, the festival continued to give a hearing to new and old works by American composers of every genre including songs from Tin Pan Alley and balladeer Woody Guthrie. In 1947 the 8th festival concluded with jam session including Tony Parenti on clarinet, Clarence Williams on piano, Pops Foster on bass and Baby Dodds on drums. The following year saw the Thelonious Monk Quartet make an appearance. Now, a decade in there was a healthy dose of the blues with one of Leadbelly’s final performances followed by Ruby Smith ‘channeling’ Bessie Smith, and the versatile Brownie McGee and Sonny Terry. By 1950 Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, Morton Gould, Paul Creston and Deems Taylor all had first radio performances of their work aired on the American Music Festival. There was a significant jazz presence too highlighted with performances by Miles Davis performed and Stan Getz and an interview with Teddy Wilson.

In 1951 plans for the upcoming 12th WNYC American Music Festival had to be altered for Cold War concerns. The series was to have featured avant-garde composer Edgar Varese’s, “Ionization.” The work called for the use of a siren “as a singing voice among some forty percussion instruments.” But WNYC had to rule it out with regrets since the New York City Civil Defense Office banned all sirens except those used for air-raid warnings.

In 1952 the widow of conductor and composer Serge Koussevitzky awarded WNYC the Koussevitzky Music Foundation’s first award for public service because the festival had, “encouraged creative talent, sent joy and beauty in the form of fresh musical ideas into the homes of its citizens and brought honor to its name.”[9] 1952 also saw the first appearance of the composer John Cage at the American Music Festival. Cage was described as a “younger upstart” whose experiments in rhythm produce “a strange phantasmagoria characteristic of the nation whose music can no more be classified than its society.”[10] In 1953, Leopold Stokowski conducted the festival’s final concert at the Museum of Modern Art. The bill included Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question, and Letter from Morocco by Peggy Glanville-Hicks.[11] It was performed on Lincoln’s Birthday in 1960 at Town Hall in New York by the National Association of American Composers and Conductors Festival Orchestra under the direction of Alfredo Antonini.

It’s worth noting that in 1967 the folksinger Oscar Brand, a long-time station producer, arranged an American Music Festival folk concert at Carnegie Hall with Arlo Guthrie, John Hammond, Tom Paxton, Jean Richie and Len Chandler. Guthrie performed Alice’s Restaurant, described by The New York Times as “an amusing but pointed spoken monolog on the vagaries of law enforcement, the selective service draft and their relation to the war in Vietnam.”[12]

By its 30th year, in 1969, the number of live festival concerts had dropped off from a peak at the beginning of the decade. As the 1970s came in, so too did the city’s burgeoning fiscal problems that were well reflected in the declining American Music Festival programs.

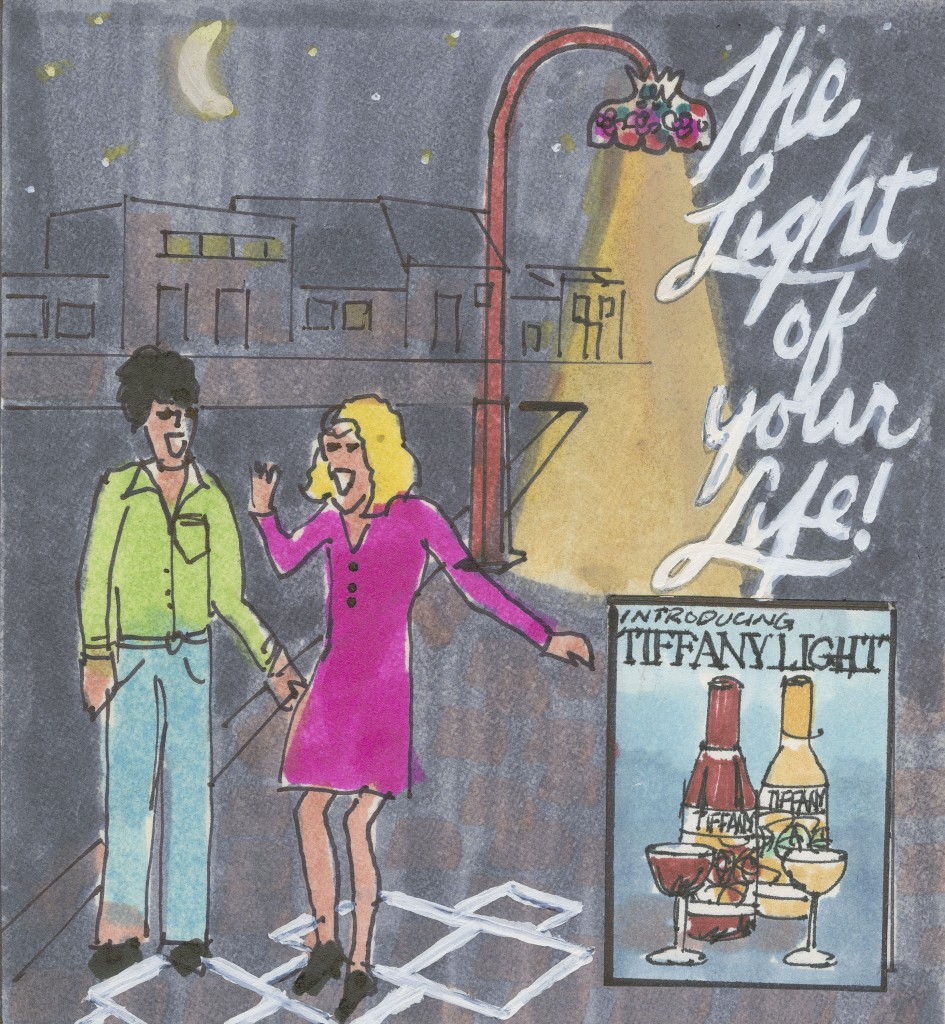

The festival as a vibrant venue for a series of live concerts was revived for a while in the 1980s and with it came not so much a festival but what was called an “Americathon” a daylong live performance that spanned the whole range of American music, from Pulitzer Prize winning composers like Ellen Taaffe Zwilich and David Del Tredici to folk musicians like John McCutcheon and alternative pop singers like the The Roaches to improvising musicians like Muhal Richard Abrams. The programs also included harder to classify ensembles like Butch Morris’ “Conditions” who conducted improvisations by with large-scale ensemble and Music For Homemade Instruments whose load-in of auto brake drums, refrigerator racks and similar “gear” made the backstage area look more like a landfill. These were performed before a live audience in places like the New School, the Juilliard School, and Symphony Space, and broadcast live throughout the day and the evening. Since then, however, the “festival” as such has been largely a designated time for playing pre-recorded American music with occasional live studio and/or concert performances.

The WNYC American Music Festival was extremely successful in achieving its goals for more than four decades. It was a pioneering effort that became a major New York cultural institution. It promoted the work of American composers, musicians, and conductors. It gave them a fair hearing. In the classical realm, it gave the WNYC listening audience a chance to reflect on American music long overshadowed by the European masters. Overall, it helped to move folk and traditional American music into the mainstream by giving equal weight to all genres of performance.

Finally, seldom mentioned but always present in its heyday and beyond for more than 40 years of festivals was WNYC’s Music Director, Dr. Herman Neuman. As a conductor and composer, he was also on the bill leading festival orchestras over the years. In 1966, some 50 works were performed for the first time at the festival. Perhaps he summed it up best saying, “Some of the music was good, some indifferent, some lousy, but now at least the composers have heard how their works sound in performance.”[13]

By the late 1980s, WNYC’s American Music Festival had run its course. The last few festivals were a shadow of their former glory as eleven days of live concerts were compacted into a day-long “Americathon”. This single day of performances was sandwiched between scheduled broadcasts of American music drawn largely from commercial recordings.

Click here to listen to archive copies of American Music Festival programs on the web.

Village Voice Ad for WNYC’s Americathon ’84.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

_________________________________________________

[1] Lohman, Sidney, “One Thing And Another WNYC Opens Annual Festival on Tuesday,” The New York Times, February 10, 1946, p.51.

[2] Downs, Olin, “Results of Five Radio Festivals,” The New York Times, February 20, 1944, p. x5.

[3] “40 WNYC Concerts to Give U.S. Music,” The New York Times, February 3, 1940, p.9.

[4] “U.S. Music Draws Audience of 3,000,” The New York Times, February 13, 1941. p.24.

[5] Sources indicate that the American Music Festival in 1942 did continue although its clear some momentum was lost. Another reason for the paucity of festival recordings during WWII is due to a change in media from aluminum to glass-based lacquer transcription discs.

[6] “100 Composers Set For WNYC Festival,” The New York Times, August 6, 1943. p.9

[7] Kennedy, T.R., “WNYC And A Musical Tradition,” The New York Times, February 13, 1944, p. x9.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “WNYC is Honored For Work in Music,” The New York Times, February 13, 1952, p. 35

[10] Downs, Olin, “Foster To Cage: WNYC American Music Festival Presents Native Music of All Characteristics,” The New York Times, February 17, 1952, p. 95

[11] Downs, Olin, “Stokowski Conducts Final Concert of WNYC’s Annual Music Festival,” The New York Times, February 23, 1953, p. 20.

[12] “WNYC Folk Concert Sung in 6 Segments,” The New York Times, February 19, 1967, p.71.

[13] “Army Band Concert Closes WNYC’s Fete,” The New York Times, February 23, 1966, p. 45.

![]()

Fiona Ross is a pioneer in the field, beginning with over a decade at the helm of Linotype’s non-Latin font division. She recently received the

Fiona Ross is a pioneer in the field, beginning with over a decade at the helm of Linotype’s non-Latin font division. She recently received the

![“The northern way is pleasanter than the southern in that one passes over mountains most of the way, and the khans are better on the whole…I was absent from Harpoot almost five weeks, and two days was the longest time I spent in any one place, so you may know life in one way did not become monotonous. Our principal topic of conversation between here and Sivas was our rascally arabdaji [guides]. This was my first experience of travelling in Turkey without a man, and I find a woman has to do a deal of fighting to get along alone.”](https://consecratedeminence.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/turkey-no596.jpg?w=500&h=286)