In November of 1981, an item appeared in The New York Times -and it seemed all of us in New York (and elsewhere) who were interested in music, radio, and culture in general, saw it:

“Teresa Sterne,” it read, “who in 14 years helped build the Nonesuch Record label into one of the most distinguished and innovative in the recording industry, will be named Director of Music Programming at WNYC radio next month.” The piece went on to promise that Ms. Sterne, under WNYC’s management, would be creating “new kinds of programming -including some innovative approaches to new music and a series of live music programs.”

This was incredible news. Sterne, by this time, was a true cultural legend. She was known not only for those 14 years she’d spent building Nonesuch, a remarkably smart, serious, and daring record label —but also for how it had all ended, with her sudden dismissal from that label by Elektra, its parent company (whose own parent company was Warner Communications), two years earlier. The widely publicized outrage over her termination from Nonesuch included passionate letters of protest from the likes of Leonard Bernstein, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland —only the alphabetical beginning of a long list of notable musicians, critics and journalists who saw her firing as a sharp blow to excellence and diversity in music. But the dismissal stood.

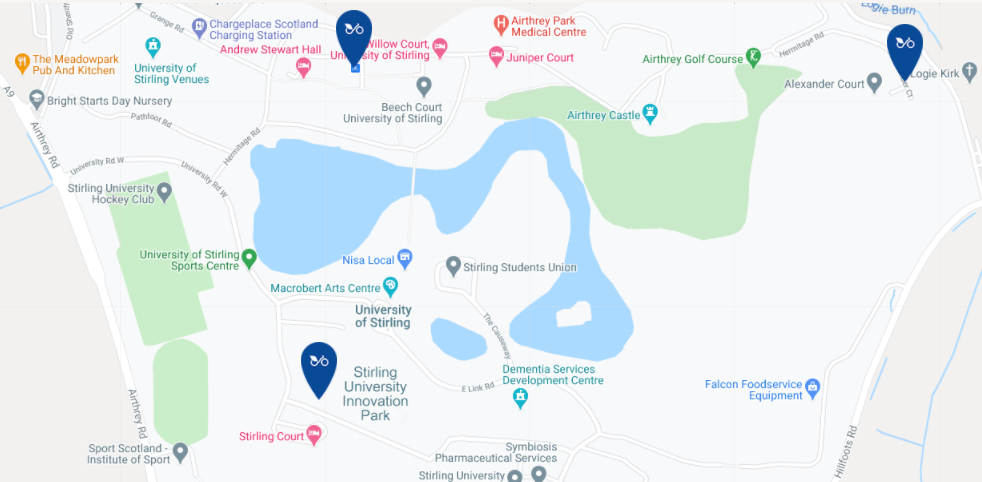

By coincidence, only three weeks before the news of her hiring broke, I had applied for a job as a part-time music-host at WNYC. Steve Post, a colleague whom I’d met while doing some producing and on-air work at New York’s decidedly non-profit Pacifica station, WBAI, had come over from there to WNYC, a year before, to do the weekday morning music and news program. “Fishko,” he said to me, “they need someone on the weekends -and I think they want a woman.” My day job of longstanding was as a freelance film editor, but I wanted to keep my hand in the radio world. Weekends would be perfect. In two interviews with executives at WNYC, I had failed to impress. But now I could feel hopeful about making a connection to Ms. Sterne, who was a music person, as was I.

Soon after her tenure began, I threw together a sample tape and got it to her through a contact on the inside. And she said, simply: Yeah, let’s give her a chance. And so it began.

Tracey—the name she was called by all friends and colleagues — seemed, immediately, to be a fascinating, controversial character: she was uniquely qualified to do the work at hand, but at the same time she was a fish out of water. She was un-corporate, not inclined to be polite to the young executives upstairs, and not at all enamored of current trends or audience research. For this we dearly loved her, those of us on the air. She cared how the station sounded, how the music connected, how the information about the music surrounded it. Her preoccupations seemed, even then, to be of the Old School. But she was also fiercely modern in her attitude toward the music, unafraid to mix styles and periods, admiring of new music, up on every instrumentalist and conductor and composer, young, old, avant-garde, traditional. And she had her own emphatic and impeccable taste. Always the best, that was her motto —whatever it is, if it’s great, or even just extremely good, it will distinguish itself and find its audience, she felt.

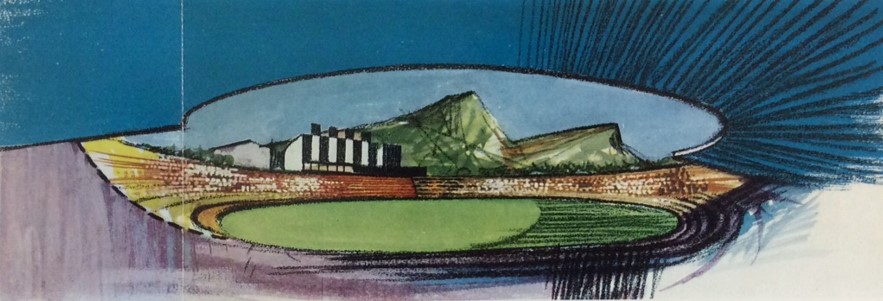

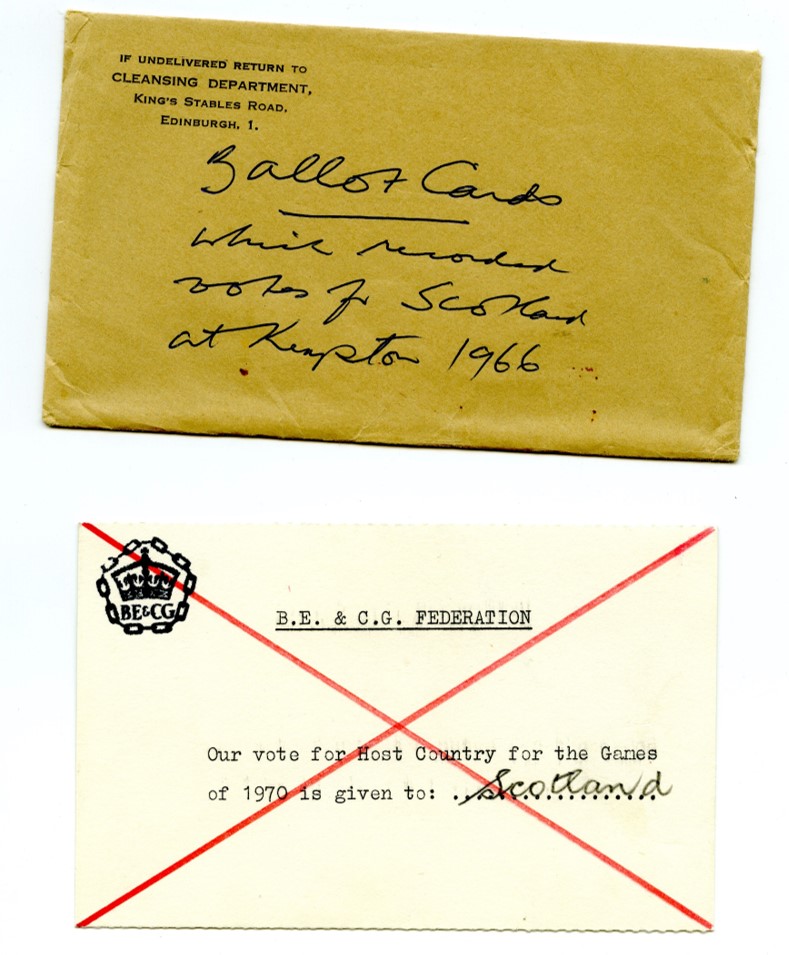

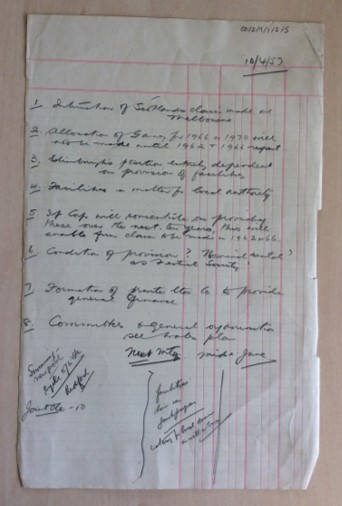

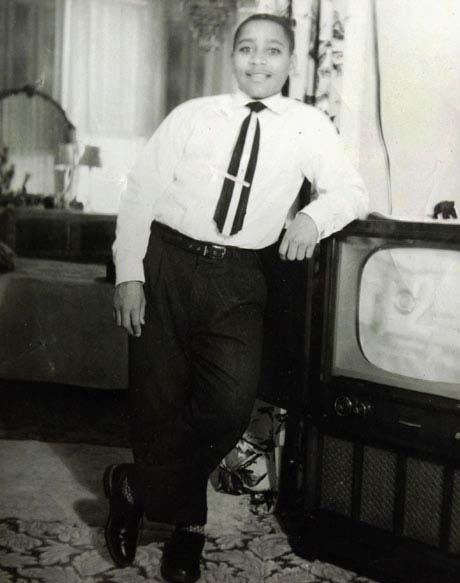

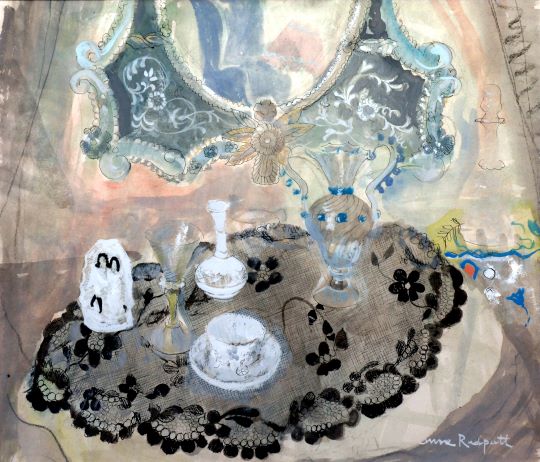

Tracey Sterne, age 13, rehearsing for a Tchaikovsky concerto performance at WNYC in March 1940.

(Finkelstein/WNYC Archive Collections)

She had developed her ear and her convictions, as it turned out, as a musician, having been a piano prodigy who performed at Madison Square Garden at age 12. She went on to a debut with the New York Philharmonic, gave concerts at Lewisohn Stadium and the Brooklyn Museum, and so on. I could relate. Though my gifts were not nearly at her level, I, too, had been a dedicated, early pianist and I, too, had looked later for other ways to use what I’d learned at the piano keyboard. And our birthdays were on the same date in March. So, despite being at least a couple of decades apart in age, we bonded.

Tracey’s tenure at WNYC was fruitful, though not long. As she had at Nonesuch, she embraced ambitious and adventurous music programming. She encouraged some of the on-air personalities to express themselves about the music, to “personalize” the air, to some degree. That was also happening in special programs launched shortly before she arrived as part of a New Music initiative, with John Schaefer and Tim Page presenting a range of music way beyond the standard classical fare. And because of Tracey’s deep history and contacts in the New York music business, she forged partnerships with music institutions and found ways to work live performances by individual musicians and chamber groups into the programming. She helped me carve out a segment on air for something we called Great Collaborations, a simple and very flexible idea of hers that spread out to every area of music and made a nice framework for some observations about musical style and history. She loved to talk (sometimes to a fault) and brainstorm about ways to enliven the idea of classical music on the radio, not something all that many people were thinking about, then.

But management found her difficult, slow and entirely too perfectionistic. She found management difficult, slow and entirely too superficial. And after a short time, maybe a year, she packed up her sneakers —essential for navigating the unforgiving marble floors in that old place— and left the long, dusty hallways of the Municipal Building.

After that, I occasionally visited Tracey’s house in Brooklyn for events which I can only refer to as “musicales.” Her residence was on the Upper West Side, but this family house was treated as a country place, she’d go on the weekends. She’d have people over, they’d play piano, and sing, and it might be William Bolcom and Joan Morris, or some other notables, spending a musical and social afternoon. Later, she and I produced a big, New York concert together for the 300th birthday of Domenico Scarlatti –which exact date fell on a Saturday in 1985. “Scarlatti Saturday,” we called it, with endless phone-calling, musician-wrangling and fundraising needed for months to get it off the ground. The concert itself, much of which was also broadcast on WNYC, went on for many hours, with appearances by some of the finest pianists and harpsichordists in town and out, lines all up and down Broadway to get into Symphony Space. Throughout, Tracey was her incorruptible self — and a brilliant organizer, writer, thinker, planner, and impossibly driven producing-partner.

I should make clear, however, that for all her knowledge and perfectionistic, obsessive behavior, she was never the cliche of the driven, lonely careerist -or whatever other cliche you might want to choose. She was a warm, haimish person with friends all over the world, friends made mostly through music. A case in point: the “Scarlatti Saturday” event was produced by the two of us on a shoestring. And Tracey, being Tracey, she insisted that we provide full musical and performance information in printed programs, offered free to all audience members, and of course accurate to the last comma. How to assure this? She quite naturally charmed and befriended the printer — who wound up practically donating the costly programs to the event. By the time we were finished she was making him batches of her famous rum balls and he was giving us additional, corrected pages —at no extra charge. It was not a calculated maneuver -it was just how she did things.

You just had to love and respect her for the life force, the intelligence, the excellence and even the temperament she displayed at every turn. Sometimes even now, after her death many years ago at 73 from ALS, I still feel Tracey Sterne’s high standards hanging over me —in the friendliest possible way.

___________________________________________

Sara Fishko hosts WNYC’s culture series, Fishko Files.