Frederick Goddard Tuckerman, Sonnet V: XVI

Between March 15 and May 17, 1857, there were thirteen births recorded in Greenfield, Massachusetts. In the same two months, there were four maternal deaths from puerperal fever (or “childbed fever”), a highly contagious infection. Those were not good odds for a pregnant woman.¹

The third of those four deaths, on May 12, was that of Anna (formally Hannah) Tuckerman, beautiful and deeply beloved wife of poet Frederick Goddard Tuckerman (1821-1873). Anna was 29 and had already borne three children, one of whom had died shortly after birth, while the other two, Edward and Anna, were now, in 1857, children of 7 and 4 respectively. The fourth birth – that of her son Frederick – went well enough at first; that is, the child was born on May 7 and lived. But shortly after his birth, Anna began to suffer the effects of the infection. Letters in the archives from shocked relatives – her husband’s aunt, her sister- and brothers-in-law – reveal that she “suffered fifty convulsion fits & seemed to suffer intensely” and that her illness lasted five days. Her husband, who was probably with her all through the birth and subsequent illness, was “all but frantick [sic] with grief…” “What will poor Frederick do!” wrote his sister-in-law, Sarah Tuckerman, ” and those poor children too, left without a mother! How short is life, how near is death to us. I feel so sad that I can hardly write.”

Puerperal fever victims suffer from a bacterial infection “caused by organisms such as the Group A Streptococcus (GAS) bacteria which, if untreated, may lead to toxic shock syndrome, multi-organ failure and death.” The bacteria cause heavy fever as the infection spreads and the abdomen swells with peritonitis. There is usually intense pain: “the severity of the pain often increased to such intensity that there are many reports of patients who emitted a continuous cry of agony or alternatively were frozen in speechless terror by the severity of their pain.”² Occasionally the sufferer experienced a diminution of the pain that appeared to mean an improvement in the case, when in fact it meant that death was imminent.

I make these observations about Anna’s death because it was an event that affected her widower profoundly, and for the rest of his life. Of the poetry Frederick Tuckerman wrote after the event, much is suffused with his memory of Anna and his sense of loss.³ Her violent end haunted him, and it haunts those of his readers who know the story and can imagine that “one mild face, with suffering lined.” He came by his grief honestly.

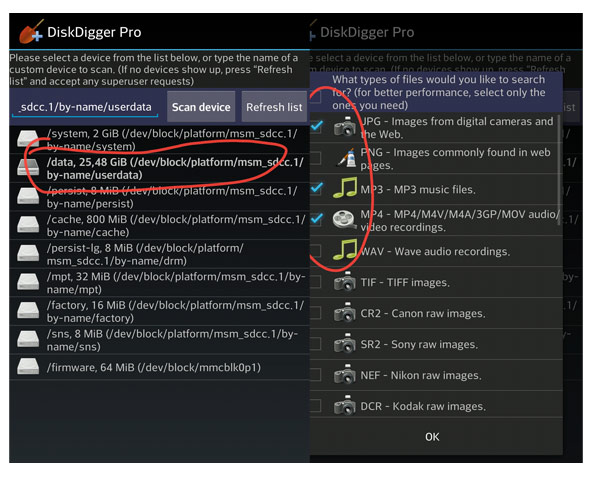

Anna and Frederick have been on my mind recently because in 2013 we received as gifts a small collection of images of the couple. A few of them have been published before, but in poor reproductions, and a few have never been published. Frederick’s birthday was in early February, so to mark the occasion here are the images. Click on any image for a larger gallery view.

![Frederick G. Tuckerman, ca. 1860. [Melainotype?]. Gift of Thomas Michie, 2013.](https://consecratedeminence.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/frederick-g-tuckerman-ca-1865.jpg?w=128&h=150)

Frederick Tuckerman has often been referred to as a “forgotten” or “neglected” poet, and yet his work has been published in several volumes (beginning with his own privately published volume in 1860, reprinted thereafter) and reviewed many times. He has been anthologized. There is a biography. Harvard owns most of his manuscripts. Behold — he has a Wikipedia page. He is not hard to find. Perhaps it is time, then, that we cease to refer to him as “neglected” or “forgotten” — those words have the ring of a self-fulfilling prophecy, and of pathos. The most recent publication of his work is in Ben Mazer’s wonderful volume “Selected Poems of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman” (2010), with its introduction by Professor Stephen Burt of Harvard. Because I could not possibly say it better, and because I’m happy to plug the book, here are several quotes from Burt’s introduction about Tuckerman, with page numbers in parentheses afterward:

Tuckerman had a superb ear, a sense of the music in a pentameter line, rare in any country or century. He had, too, a sensitive, and an unflinching attention to the psychology of mourning; and he made a strenuous and reflective attempt to reconcile his melancholy temperament with religious faith. (Introduction: x)

He showed his technique in a panoply of sonnets whose variety expanded the limits of the fourteen-line form. He did so as a poet of New England, of its landscapes, its local history (“Wassahoale” and “sagamore George”), and especially its plant life: he became an American poet of natural history, the American poet who best records the failure of the nineteenth-century enterprise called natural theology. The Tuckerman of the sonnet series looks into himself, looks at the mullein’s golden stalks and at the ocean’s crests and troughs, looks for evidence of a just God there, and discovers – perhaps without ever having read Darwin – that such evidence is not to be found. (x-xi)

Tuckerman became at once a student of grief and a student of botany, seeking at once leafy detail for its own sake (he always finds it) and evidence of God’s plan for us (which he does not find)… (xiii)

This poet of grief and of natural history is also our first dedicated American poet of the disenchanted, inhuman biosphere: as much as his rhetoric belongs to his era, as much as he does retain a Christian faith, he seems at times closer to Nature, the scientific journal, than to Wordsworth’s Nature (which ‘never did betray/The heart that loved her’)… (xiii)

In Tuckerman’s best poems natural theology, the claim that we can know God through an ordered nature, becomes inseparable from a mourner’s theodicy, the attempt to get past personal loss by proving that God’s ways are after all just. (xv; for an example of “a mourner’s theodicy,” see note 4 below.)

The sonnet sequences begin by asking – they never stop asking – how to connect flora and fauna to human loss and human truth, and whether that connection can even be made. (xvii)

The gallery of images below includes several selections from Tuckerman’s work. The poems are all from the Archives copy of his privately published edition of 1860.

Notes and selected links

(1) “Roughly speaking, there were, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, about 2-3 deaths and 6-9 cases in every 1,000 deliveries. In epidemics, of course, there were far more.” Loudon, Irvine. The tragedy of childbed fever. Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 6.

(2) Ibid, p. 7.

(3) In his biography of Frederick Tuckerman (“Beyond Romanticism,” 1990), Eugene England suggests that Frederick felt guilt over Anna’s death “perhaps for some failure to provide medical care” (p 120). I believe there is no evidence for this idea beyond the “guilt” in his poems. Anna would have had a midwife or doctor (either one probably the source of her infection) for a home birth, as was customary at the time. Furthermore, the nature of puerperal fever was that once it struck, nothing could be done — there was no other effective “medical care” to provide. Today a patient would get a course of antibiotics and most likely recover completely.

(4) As an example of “a mourner’s theodicy,” consider this excerpt from a letter about Anna’s death from Mary May, Frederick Tuckerman’s aunt, to Sarah Tuckerman, his sister-in-law: “These are sore trials. There is nothing for us to say, when such come – but that the Giver has exercised his right, & we must submit. –tis a hard lesson, & few attain it perfectly, few who sincerely say “thy will be done.” (Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Cushing-Tuckerman-Esty Papers, letter of May 24, 1857; letters quoted earlier also from this collection)

******************************************************************************

Tuckerman, Frederick Goddard. Poems (1864): http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011561943

Mazer, Ben. Selected Poems of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/456169890

Loudon, Irvine. The Tragedy of Childbed Fever: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/41419618

England, Eugene. Beyond Romanticism: Tuckerman’s Life and Poetry: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243706071

Hudgins, Andrew. “‘A Monument of labor Lost’: The Sonnets of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman”: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25305477

Groves, Jeffrey. “A Letter from Frederick Goddard Tuckerman to James T. Fields”: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3817219

Golden, Samuel. Frederick Goddard Tuckerman: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/711989

Wilson, Edmund. Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/207025

Bynner, Witter. The Sonnets of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1482436

Winters, Yvor. “A Discovery: The Cricket, by Frederick Goddard Tuckerman”: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3847469

Eaton, Walter Pritchard. “A Forgotten American Poet”: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/26405/26405-h/26405-h.htm

Tuckerman, Frederick Goddard. “The Cricket” (1950 Cummington Press version): http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/4289505

–”The Cricket,” Massachusetts Review, Autumn, 1960, vol. 2, issue 1: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25086599

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/frederick-goddard-tuckerman

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174269 (Rossetti’s “When I am dead, my dearest”)

![Frederick G. Tuckerman, ca. 1860. [Melainotype?]. Gift of Thomas Michie, 2013.](https://consecratedeminence.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/frederick-g-tuckerman-ca-1865.jpg?w=128&h=150)

![Frederick G. Tuckerman, ca. 1860. [Melainotype?]. Gift of Thomas Michie, 2013.](http://consecratedeminence.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/frederick-g-tuckerman-ca-1865.jpg?w=128&h=150)

Carmen, is turning a more friendly ear to a group of modern composers who are basking in the unaccustomed warmth of sympathy and appreciation. The exits are still in demand but at least there is no more rush.

Carmen, is turning a more friendly ear to a group of modern composers who are basking in the unaccustomed warmth of sympathy and appreciation. The exits are still in demand but at least there is no more rush.