A recent trip along the byways of a new acquisition, the Daniel and Tammy Dickinson Family Papers, reminded me of the pleasure of new discoveries, especially unexpected ones. In this case, the discoveries came while processing an unassuming little collection about the family of Daniel Dickinson, a fourth cousin twice removed (I think…) of poet Emily Dickinson (although Daniel wouldn’t have understood this claim to fame), and his wife Tammy Eastman, member of another widespread local family. This branch of the Dickinsons lived in North Amherst, where Daniel farmed the land his father had farmed before him, raised a family, and helped start the North Amherst Congregational Church.

Daniel had several brothers, among them Baxter and Austin, who are more well known today, or at least more easily discovered, than Daniel. Both brothers were clergymen, and both helped found Amherst College – Baxter with some of his modest salary, and Austin with efforts to obtain a charter.

All three Dickinson brothers had Dickinson daughters – 10 daughters in total. 7 of the 10 lived to adulthood, including Daniel’s daughter Louisa, who attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary with Emily Dickinson in 1847-48 – her name appears immediately below the poet’s in the catalogue for the year. Louisa married John Morton Greene, a clergyman who is remembered for having advised Sophia Smith to start Smith College. There is evidence that Dickinson wrote to Louisa, although the letters do not seem to have survived. It’s a stretch to imagine Dickinson and Louisa being close, lasting friends, as the latter was very religious – she seems sure to have been a “hoper,” while we know Dickinson was a “no hoper” (“those who have a hope that they are Christians and those who have no hope” — see Foreshadowings, page 10).

Louisa Dickinson, from a daguerreotype reproduced in “Foreshadowings of Smith College”

But it was Baxter Dickinson’s four adult daughters — Harriet, Martha, Mary, and Isabella — who intrigued me the most, and it was the attempt to follow their lives through the evidence in this collection that led me again to Emily Dickinson.

It has long been known that the poet corresponded with the girls’ brother William Cowper Dickinson (AC 1848). We know he was a friend of Emily’s brother Austin and visited the Dickinson home often during his years at the College, and we know he wrote her a Valentine that provoked her to characterize it as ”sarcastic” and his tone as that of “an Eagle, stooping to salute a Wren” (one wonders whether he was also the intended recipient for the unsent, contemporaneous envelope labeled “With the sincere spite of a Woman”).

Ouch…: “A little condescending, and sarcastic, your Valentine to me…a little like an Eagle, stooping to salute a Wren, & I concluded once, I dared not answer it, for it seemed to me not quite becoming — in a bird so lowly as myself — to claim admittance to an Eyrie, & conversation with it’s King.” 14 February, 1849. AC Transcript 62/Johnson Letter 27; original last noted in possession of WC Dickinson’s son Clarence.

“With the sincere spite of a Woman.” (AC ED 886)

We know too that the poet also corresponded with at least three (Harriet, Martha, and Mary) of Baxter Dickinson’s daughters, whom she met in 1851 when she travelled to Boston to consult a physician. At the time, Baxter Dickinson was the Agent and Secretary of the American and Foreign Christian Union in Boston, and his daughters were probably with him and their mother in the city. Perhaps Emily Dickinson sought out the family because of her earlier acquaintance with their lofty brother. The correspondence that probably began there is now lost (although I hold out hope for attics yet unraided), and details about Dickinson’s correspondents seemed lost as well.

Happily, a dozen letters from Baxter Dickinson to brother Daniel in the Daniel and Tammy Dickinson Papers provide some details about his daughters, illustrating that the girls were cherished, well-educated, and important to the family’s well-being. While son William C. Dickinson grew up, moved away, and became a clergyman and educator himself, the adult daughters remained with their parents, moving among the handful of states where Baxter took up various posts and going to school at several different institutions (including the Auburn Female Seminary and the Lasell Female Seminary). The family moved to Lake Forest, Illinois in the second half of 1859 and promptly opened their own school, the Dickinson Seminary for Young Ladies. One of Baxter’s letters suggests that the parents worked for their daughters in the school, and not the other way around: “The four daughters (‘Miss Dickinson’ at the head) are carrying on with enthusiasm & energy the school enterprise, with such help as their Father & Mother render – which I believe they as well as we regard as very far from being unimportant.” (Baxter Dickinson to brother Daniel Dickinson, May 14, 1861.)

Dickinson Seminary for Young Ladies in Lake Forest, Illinois, ca. 1865

Through Baxter’s letters we learn that Emily Dickinson’s female cousins were teachers, and of many different subjects, and that they traveled far (including European trips) and were, like her, in no hurry to marry. One of them, Harriet Austin Dickinson, became a faculty member at the Packer Collegiate Institute, working there for decades. This photograph from her 1913 obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle is the only photograph of the sisters I’ve managed to find so far.

Speaking of marrying, only one of Baxter Dickinson’s daughters married – his daughter Isabella. And when I learned the names of her husband and children, another small piece of the sprawling puzzle that is Emily Dickinson fell into place.

Wallace and Austin Keep

Isabella Dickinson married John Haskell Keep, a member of the long-established Keep family of Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Two of Isabella’s sons were Wallace Huntington Keep and Austin Baxter Keep, both of whom went to Amherst College – Wallace was Class of 1894 and Austin, 1897. The sons are known to Dickinson scholars due to their involvement in the circa 1847 daguerreotype of the poet: in 1932 Austin provided Emily Dickinson’s editor Mabel Loomis Todd and scholar Millicent Todd Bingham with reproductions from his own cabinet card of the daguerreotype, and in 1945 Wallace sent Bingham the original daguerreotype. How did Wallace Keep come to possess this now priceless daguerreotype? For the full story, see Millicent Todd Bingham’s “Appendix 1” in Emily Dickinson’s Home, but for our purposes it’s useful to know that until Wallace’s gift in 1945 the only photographic images of Emily Dickinson were reproductions of two cabinet cards of the daguerreotype. Mabel Todd had used one in her possession for the 1931 edition of Letters of Emily Dickinson.

Reproduction used in the first and second printings of Mabel Loomis Todd’s 1931 edition of “Letters of Emily Dickinson”

Reproduction from Austin Keep’s cabinet card, in third printing of 1931 edition of “Letters”

The daguerreotype Wallace Keep sent to Millicent Todd Bingham in 1945, now at Amherst College

Once I understood that that Wallace and Austin Keep were sons of a woman who had known Emily and Lavinia Dickinson during their youths, I then understood something that seems to have perplexed Millicent Todd Bingham, who seemed almost suspicious (“what was my amazement…it seemed incredible”) of the Keep family’s possession of the daguerreotype: despite how it looked later, it was very logical (if still impetuous) for Lavinia Dickinson to have given her sister’s daguerreotype to Wallace during a visit he made to her home in early June, 1892, a visit perhaps in connection with a talk about Emily Dickinson that Mabel Todd had given at Amherst College on June 2. Perhaps Wallace attended the talk and had his Amherst cousins in mind and so paid a visit to Lavinia. He later remembered having visited the Homestead several times, the first time with his mother, probably when he arrived as a freshman at Amherst. To Lavinia, the youthful Wallace no doubt reminded her of better days before the “war between the houses” and the damage to relationships among the family. Lavinia would have viewed Wallace as “family,” but family without complications. The daguerreotype would be safe with him, as in fact it was. That she apparently claimed later that it belonged to Margaret (Maggie) Maher, the family’s employee, was perhaps a “misdirect” manufactured to prevent having to admit how she’d really disposed of it (why she may have correctly assumed no one would ask Maggie for it is another question). Or it may be that Maggie possessed a cabinet card of the daguerreotype and it was what was actually meant in early references to the “daguerreotype.” Whatever the details, all trace of the original daguerreotype disappeared after 1892, and when Wallace Keep sent it to Bingham in 1945, she was astonished at its reappearance. Because I hadn’t understood the relationship between the Keep brothers and the Amherst Dickinsons, I had shared her confusion, but the letters in the Daniel and Tammy Dickinson Family Papers removed the mystery.

This long, winding post is meant to remind readers who have gotten this far of the joys of research and unexpected discoveries, as well as the satisfaction in being able to make connections between subjects. What I knew of Emily Dickinson gave me insight into the Daniel Dickinson family, and what I learned from the latter added details to what I knew about the poet – and together they have a lot to teach about life in the 19th century. Admittedly, the information one finds is often of minor significance in the scheme of one’s own life, but the work takes us out of ourselves and into other worlds and times. More importantly, even little discoveries add something to the body of knowledge for a given subject.

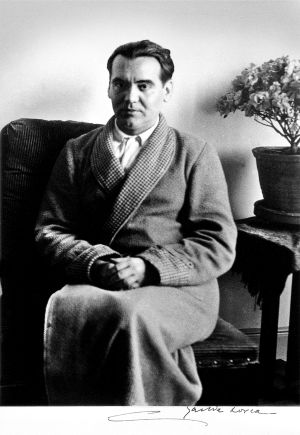

had been told to tell him how much he meant to us all here and how greatly his genius and musicianship had influenced our musical lives. The master listened in silence and then rose and delivered to me one of those magnificent and stirring speeches for which he was was famous. He completely turned the tables on me. How much had meant to us here? Nonsense! How much had we here meant to him and how deeply grateful he was to us for great love and appreciation for him, and would I please go back and tell that to New York? It was typical of the man. When I left him in the early morning I had a vision I shall never forget: the private car of the master silently pulling out of the station in the softly falling snow, bound for who knows what future triumphs.

had been told to tell him how much he meant to us all here and how greatly his genius and musicianship had influenced our musical lives. The master listened in silence and then rose and delivered to me one of those magnificent and stirring speeches for which he was was famous. He completely turned the tables on me. How much had meant to us here? Nonsense! How much had we here meant to him and how deeply grateful he was to us for great love and appreciation for him, and would I please go back and tell that to New York? It was typical of the man. When I left him in the early morning I had a vision I shall never forget: the private car of the master silently pulling out of the station in the softly falling snow, bound for who knows what future triumphs.