THE ORIGINS OF THIS COLLECTION

A Childhood Spent Preparing

I think it was actually a confluence of four factors that led me, enabled me, to conduct The Distinguished Contemporaries Collection of Interviews.

First, I am a lifetime insomniac. Beginning at age six, I never missed Barry Gray, “The Father of Talk Radio” from 11PM—1AM on WMCA, New York, and the over-nighters like Long John Nebel and Barry Farber. They kept me company. I could see them, the guests, and their studios in my mind’s eye.

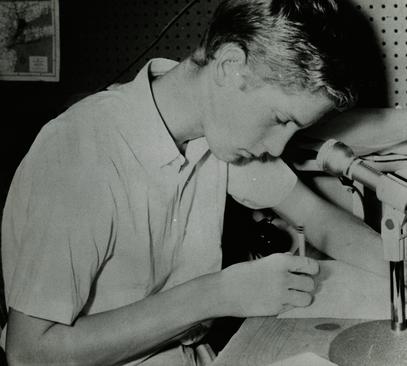

Second, my environment as a kid was not typical. I can’t ever remember playing ball. But I’m full of memories of acting as DJ with my neighbor Mike Hayes as engineer in our basement studio, where we had a low-power, FCC-approved, neighborhood radio station. Just down the hall, Mike’s parents, Peter Lind Hayes and Mary Healy, earlier of theater, film, Vegas, and television notoriety, played hosts to well-known guests on WOR radio every morning. At times they would call on me to report the weather (my other avocation). Sometimes I’d chat with a guest like Pat Boone or watch Peter upstairs in the “Red Room” recording telephone interviews with Richard Nixon or Bob Hope. I later used this forum when a distant guest had minimal availability, recording telephone conversations with Arthur Hailey, Milton Friedman, Wernher Von Braun, Ann Landers and others.

Access to the airwaves and to celebrities came early for me. I clearly remember when Walter Cronkite guested on the Hayes’ program; he popped his head into our studio, sat down and took questions “on air,” though we didn’t have the good sense to record it as teenagers.

While at The Lawrenceville School, in New Jersey, I got my on-air fixes only on holidays (though I hid a radio inside my pillow to take in WOR’s Jean Shepherd at night). As a senior, I was in the Radio Club, and we started an FM station run from my dorm room. Soon after, the school designated the rather ancient Bath House as our new headquarters for WLSR. As a news fanatic, my journalistic coup was to scoop the weekly student paper by interviewing the head master or coaches before their stories appeared in print.

In late December 1967, my best friend, Sherwin Harris, and I were home from our respective schools. My parents held a small, black-tie party for their anniversary. It was just after Christmas, and the gift given me that holiday was the latest in home entertainment, a black-and-white, reel-to-reel video recorder. When I learned that Walter Cronkite would be a guest at the party, Sherwin and I yanked out the Who’s Who in America and made notes on his biggest stories and also the issues of that day, such as Vietnam. At 11 PM, toward the end of the party, Cronkite sat down and gave us a twenty minutes that you’d never hear on TV. And, although that early video tape didn’t survive, still thanks to my dear friend’s foresight, a photo and the audio recording remain for you to see and hear.

The Cadence of a Weekly Program

In the fall of 1968, I entered Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, and quickly located the basement offices and studios of WRTC, an FM station with a broadcast radius of about thirty miles. The campus was as consumed with the issues of the day—war, race, feminism—as with coursework. In light of the school’s heavily male vs. female ratio, a lot of guys were focused on weekend road trips to the closest all-night party. For me, however, the lure was going to New York or to the celebrity homes where I’d made interview appointments with the likes of Salvador Dalí at the St. Regis Hotel in the City, where he wintered, or with Norman Rockwell in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

I encountered excellent cooperation from the campus weekly, The Trinity Tripod. The editor gave me good space, and often a photo for the program, which they dubbed, “Cooper’s Show.” The paper did not see us as a competitor, but as a collaborator in education and public service. This homage to “the public good” a few years later became crucial in my successes lining up a syndicate of commercial radio stations.

At my graduation in 1972, I received a B.A. in English, with Spanish as a minor, de rigueur in the era of the “well-rounded” liberal arts major. I was flanked by two honorary degree recipients at polar extremes of the arts vs. sciences: Edward Albee, who’d been dismissed years earlier from Lawrenceville AND Trinity for failure to attend classes, and my Dad, Dr. Irving S. Cooper, for his pioneering discoveries as a neurosurgeon (although he was a liberal arts man too, writing an M.S. thesis, Medical Aspects of the Death of Desdemona).

Having honed my research and articulation skills, the former deep in the remote shelves of the Watkinson Library, the latter conducting and editing my weekly show and reading news copy live on the air, I shortly landed a weekly slot on a powerful FM station, WKSS, serving Hartford, New Britain, and Middletown, Connecticut, with a broadcast radius of 75 miles.

I fell back on a few reliable guests and then switched to local elites. I taped a broadcast with Dick Newfield, President of Hartman Tobacco. Who knew Connecticut grew superlative cigar tobacco leaf? My interview with outspoken Hartford Mayor George Athanson, though, ended my run at the station. The mayor was witty and charming but also expressed arch liberal views on getting out of Vietnam. The station manager refused to air the program in its regularly scheduled Sunday half hour. I said nothing, walked down the spiral stairway and out WKSS’ glass doors for the last time.

Public Interest vs Commerce in 1970s Broadcasting

Thomas Wolfe wrote that, “You can’t go home again,” but I must’ve missed that class: I drove straight home to Pelham in the Westchester County suburbs of New York City, and signed up for graduate business courses that fall at Iona College, a commuter school about seven miles away in New Rochelle. There I found that George O’Brien, in retirement from WQXR, had carved out an arm of the School’s development office, and called it “Radio Activities.” In his office and studio in an upstairs corner of the Ryan Library, he created interviews to run as “soft marketing” for Iona on an undefined schedule at a hundred stations across the country.

His shows, hosting faculty members and occasional outside guests, were in the mold of the FCC’s public service and education model: it was cost efficient for the stations, met the regulations on delivering public affairs to their audiences, and could be isolated outside valuable commercial prime time.

But George was not averse to my vision for “Radio,” as we shorthanded it. Why not assemble a collection of Metropolitan-area stations and feature eminent guests, to conjoin the name Iona College with respected thinkers across all the humanities, and presented exclusively in the region from which the student body was drawn?

This brings me to the vital third and fourth ingredients in my interview show’s genesis. The late 1960s and early 1970s were the last days of public service radio on commercial outlets before de-regulation began apace. It was an open door for my style of program to fill that need.

The fourth important feature of what I’ll call the opportunity terrain, was access to prominent guests. By that I mean, locate/contact/convince each prospect, a triad which, I contend, was more easily accomplished then than it would be today.

Having been salaried as assistant director with a budget, a staff of three, and the ability to dictate letters or play tapes for transcription by a large secretarial pool, I initiated the process of meeting with station managers, editing my existing tape collection to begin regular broadcasts, and arranging with the local newspaper to run transcripts, with a photo, as a weekly feature.

A syndicate of 30 stations, including the non-commercial WNYC, came together quickly. The quid pro quo was simple: give me a fixed broadcast time which I could promote, and I’d provide impressive content, reliably, and at no cost. They “bought in.”

As for on-going access to top-notch guests, presented exclusively, I had three things going for me: I could write or call targeted personalities with a good story as to who’d been recent guests, and offer a mass audience. I knew how to research out the man or woman’s street address to write to them. I could also ask the operator to connect me with “information” for their particular town (celebrities were shielded, hidden, back then, from today’s nation-wide 411 and the web, which has pushed them to be unlisted and “underground”). I could make it nearly impossible for my prospective celebrity guests to say “no,” by requesting, “You name the time, and you name the place.”

Only three people turned me down between 1967 and 1974: Nobel Prize-winning writer Pearl Buck (The Good Earth). Her personal assistant asked for a fee. Author John Updike, wrote that he’d done enough interviews for a lifetime. And science fiction great Isaac Asimov called me on the telephone and said, “But I just did an interview for TV, and they paid me $500.”

I had another asset when I arrived for the interviews. I was in my early twenties at the time. My guests were mostly at the end of their careers and I was “a kid.” The artist Thomas Hart Benton, comparing me to himself, called me a “baby.” James Michener asked why I hadn’t stayed at his house instead of a motel, then took me to town for lunch as did former Kansas Governor Alf Landon. No matter how foolish my questions, each guest responded as though I’d had an insightful epiphany that demanded an unabridged and serious response.

George O’Brien ultimately stood down, making me Iona’s Director of Radio. But I kept him engaged as he was still commuting from New Jersey three days a week. One day we invited Charlie O’Donnell, Dean of the Business School, to take the Eastern Shuttle to Boston, for a morning session with psychologist B. F. Skinner, at his Cambridge home, and an afternoon meeting in O’Donnell’s “bailiwick”: the office of Nobel economist Paul Samuelson at M.I.T.

About that time, I got a call from the President of Educational Dimensions in Connecticut. They were selling cassette tapes with slides to schools around the country. In the 1970s, before the internet became commonplace, this was a very popular format. I did a set of career interviews for them: beauty operator, plumber, etc. But more importantly, it triggered the idea of founding my own company, Sound Perspectives. My girlfriend’s art-director father put together a great mailing piece on my theme: In-depth Interviews with people who don’t give interviews. It included a flexible plastic record, our announcer identifying the purposes of the recordings, interspersed with clips from W. H. Auden in his dank St. Marks apartment, Walter Cronkite at CBS, James (Michener at his Pennsylvania home, Norman Rockwell at his Stockbridge, Massachusetts, studio, and B.F. Skinner in his basement office near Harvard.

(insert Sound perspectives sampler here)

Iona College drafted a document by which I was salaried and given a budget to produce the interviews as radio PR for them. But I would remain the permanent owner. This gave me the opportunity to make of the collection an irrevocable gift to the Public Radio archives of WNYC and WQXR, a representative composite of which we invite you to hear:

James A. Michener, Author

Charles M. Schulz, Cartoonist “Peanuts” (by telephone)

Sammy Cahn, Songwriter (1913-1993)

Roy Wilkins, Executive Director, NAACP

John Chancellor, Broadcast Journalist

Andy Warhol, Artist

Harry Reasoner, Broadcast Journalist

Salvador Dalí, Surrealist Artist

Richard Rodgers, Composer

Norman Rockwell, Artist

Ann Landers, Advice Columnist (by telephone)

Mickey Rooney, Actor