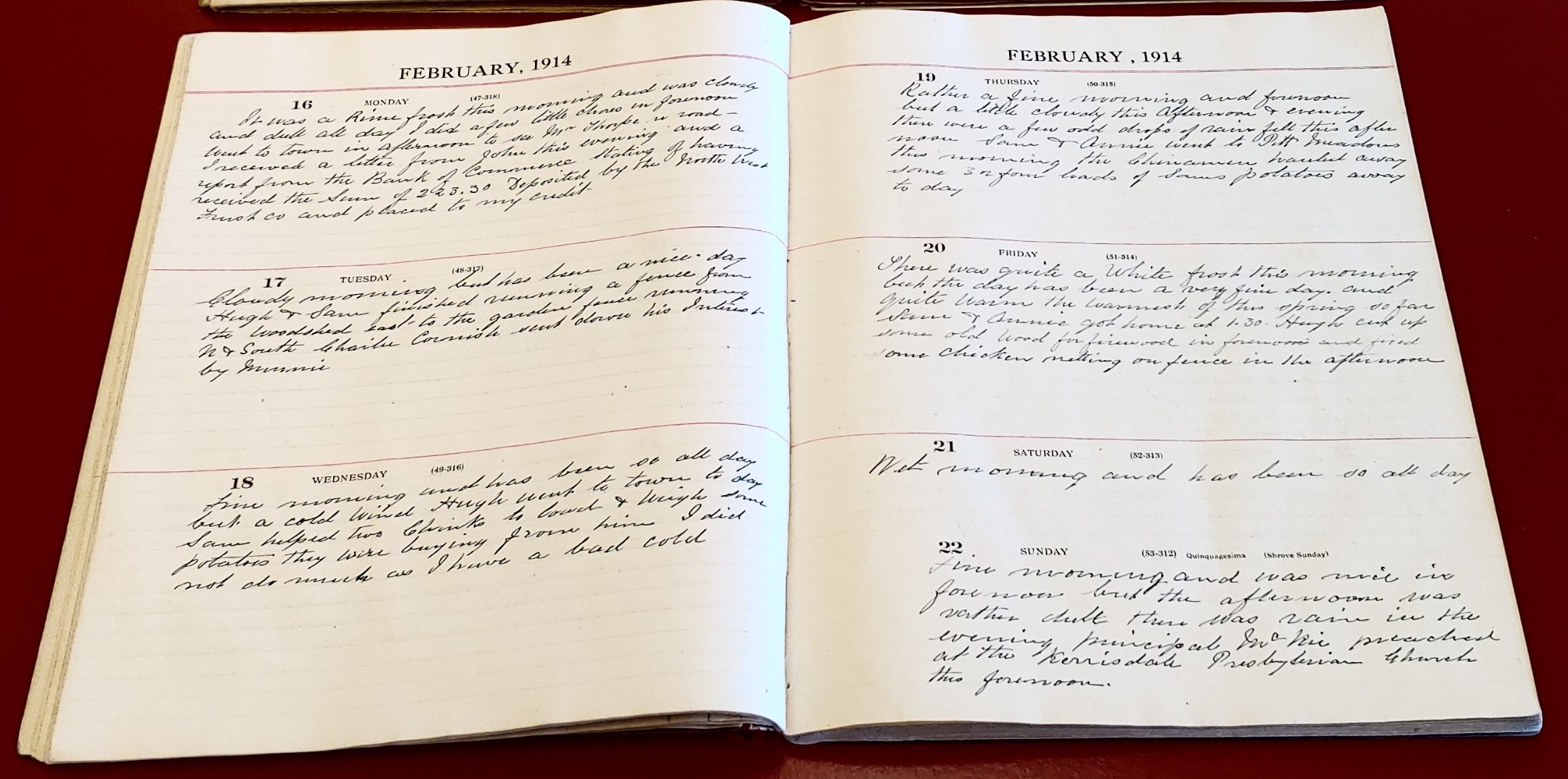

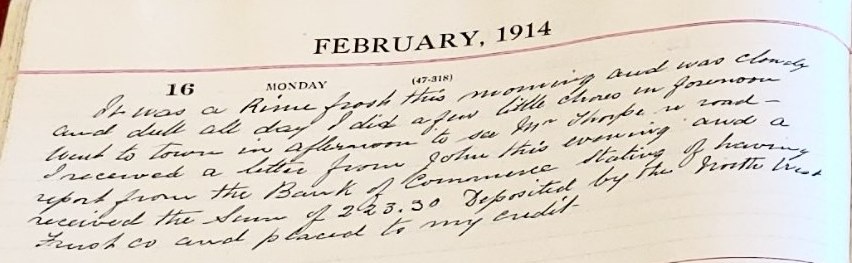

Marshall Curry’s recent documentary A Night at the Garden (produced by Field of Vision) about the German-American Bund rally in Madison Square Garden in February 1939 and The Radio Diaries piece When Nazis Took Manhattan remind us that the notion of a fascist America may not just be the stuff of fiction by Sinclair Lewis and Philip Roth, but a real possibility. Given the right social, political and economic conditions, a significant number of the voting public can indeed be persuaded by demagogues. When Radio Diaries asked the WNYC Archives if we could help with their piece, we were able to come up with two hours’ worth of the raw audio from the rally.

A poster used to promote the German-American Bund Rally at Madison Square Garden on February 20, 1939.

(Poster courtesy of Lorne Bair Books, Inc.)

Why then have we decided to make this hate-filled event available? Well, it wasn’t because it’s enjoyable listening or that we endorse any of the ideology, perceptions or language used by the speakers. To the contrary, the rally is a raw, unedited 1 hearing of an infamous event that takes place during a critical period in American history; just months away from the outbreak of World War II, when isolationist and ‘America First’ sentiment was gaining traction daily. The public rhetoric used by the German-American Bund played to the underlying assumptions of these movements by raising the fear-mongering specter of an internationalist ‘Jewish cabal’ 2 out to deprive America of its sovereignty and bring Soviet-style communism to our shores. Bund leader Fritz Kuhn put it this way:

We, the German-American Bund, organized as American citizens with American ideals and determined to protect ourselves, our homes, our wives and children against the slimy conspirators who would change this glorious republic into the inferno of a Bolshevik paradise.

Back then the ‘cabal’ was composed of FDR’s treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., the financier Bernard Baruch and the Rothschild banking family. Today, for those on the alt-right, the Jewish billionaire bogeyman is the progressive George Soros and his supporters.

Original program cover for the German-American Bund rally Madison Square Garden on February 20, 1939. Notice, the snake’s head has a hammer and sickle on it.

(U.S. Holocaust Museum via Wikimedia.)

The speakers relied on a white supremacist tautology with a bizarre American twist that employed George Washington, the nation’s founding father, as the patriotic foundation upon which to build their racist non-interventionist platform. The event, orchestrated to coincide with Washington’s birthday, (February 22nd), featured a thirty-foot image of the first President flanked by red, white and blue bunting and swastikas as the visual backdrop to a succession of uniformed Bund speakers who drew on Washington’s inaugural admonition about avoiding ‘foreign entanglements.’ One speaker even argued that if Washington was alive today, he would be a ‘staunch friend’ of Adolph Hitler. To this they added time-worn tropes, stereotypes and falsehoods about criminal Jewish refugees taking American jobs, Jews creating degenerate art and music, and Jewish teachers corrupting Aryan children.

America’s home-grown legacy of slavery, the Klan, Jim Crow laws, and, nativism fed into this anti-Semitic Nazi ideology of racial purity, making it easy for speakers to talk about Jewish carpetbaggers during Reconstruction along with miscegenation or ‘race mixing’ and ‘lustful Negroes’ who only wanted to rape white women. After all, one speaker noted, intermarriage is already illegal in more than half the nation, implying that lawmakers should just finish the job.

Father Charles E. Coughlin broadcasts in Royal Oak, Michigan, Oct. 26, 1936.

(AP Photo)

But perhaps no better domestic factor was utilized by the Bund than that of America as a Christian nation with Christian values. Here, the notoriously anti-Semitic Father Charles Coughlin, the outspoken radio evangelist, was held high as a martyr and victim of the ‘Jewish-controlled’ media. No doubt rally goers were disappointed the controversial preacher was a no-show since Kuhn had repeatedly promised a “prominent Catholic” would attend to discuss “the Jewish question” in the days leading up to the event.

This certainly didn’t dampen the address by Bund publicity director Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze, who harped on the Jewish domination of American culture and called for news and culture without “a Jewish accent.” Kunze, who fancied himself an American Joseph Goebbels, complained there is “no free speech for white men” in the United States and condemned ‘parasites’ like Walter Winchell, George Burns, Leonard Bernstein, and Eddie Cantor, for polluting the ether and taking the rightful places of Aryan Americans in the cultural milieu. In brief, he called for an ethnic cleansing of the airwaves. It’s not too much of a stretch to go from the Christian Nationalist rhetoric of 80 years ago to current alt-right allusions to Jewish control of Hollywood studios and other media outlets.

The Protests

Towards the end of Kuhn’s speech (beginning 1:57:00) you will note there’s a disruption of some kind. While we can’t see it, Kuhn asks people to remain seated and says, “one fanatic doesn’t make any difference, ladies and gentlemen…see, that’s the way we never do it.” This is the moment when protester Isadore Greenbaum mounts the stage and attempts to reach the podium but is grabbed, beaten, and, stripped by uniformed Bund members. It is Greenbaum’s story that is the focus of the Radio Diaries production. The savage assault on him is clearly shown in Marshall Curry’s documentary film produced by the short documentary unit Field of Vision.

Isadore Greenbaum being beaten and subdued by Nazi storm troopers at Madison Square Garden, February 20, 1939.

(Photo courtesy of The New York Times)

The number of protesters on the streets of New York that cold evening depended in large part on your source, with police estimates ranging anywhere from 10,000 to 100,000.3 Nevertheless, the anti-fascists were hemmed in by at least 1,700 policemen, many mounted on horses, outside of the Garden and at various points on 8th Avenue. (In 1939 the Garden was located at 8th Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets in Manhattan). The New York Times described the police cordon the following day as “a fortress almost impregnable to anti-Nazis.”

New York City’s mounted police forming a line outside Madison Square Garden to hold in check a crowd that packed the streets where the German American Bund was holding a rally.

(AP Photo/Murray Becker)

A mounted police officer attempts to take flag away from anti-Nazi demonstrator outside of Madison Square Garden, February 20, 1939.

(AP Photo courtesy of The New York Times)

The event received broad national coverage that reflected these divergent takes on what happened. The Brooklyn Eagle reported thirteen people were arrested and eight received medical attention, including four police officers in street skirmishes between Nazis, anti-Nazis and police. Yet overall, “Despite the scattered fighting in the streets, no serious trouble resulted, and the rally failed to produce the bombing and rioting predicted.”4

Socialist Workers Party protest poster against German-American Bund Rally

(Poster courtesy of Field of Vision/Marshall Curry Productions.)

People from a wide range of political and Jewish organizations protested, although only the Socialist Workers Party (whose poster is pictured here) was actually noted by the city’s paper of record.5 The communist Daily Worker, of course, avoided mentioning the Trotskyist SWP, and pulled no punches in its lead:

“The fetid stench of Hitler Fascism billowed and eddied through Madison Square’s vastness last night. Nazidom’s outpost in America, the German-American Bund, carried its war on democracy into the Garden with shouts, heils, a band of uniformed storm troopers — all the made-in-Berlin trappings, including a thin ‘Americanism’ veneer craftily plotted by German propaganda headquarters.”6

My guess is the paper would not have been as damning six months later (August 23, 1939) in the wake of the signing of the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact. Still, the Daily Worker that February remained the only newspaper to mention a simultaneous counter-rally “for true Americanism through brotherhood, through democracy,” that was held at Julia Richmond High School in Queens. Speakers there included, Acting Mayor Newbold Morris (La Guardia was out of town), Judge Anna M. Kross, Professor David Efron of Sarah Lawrence College, and WHN News Commentator George Hamilton Combs. 7

With a pair of Bund “storm troopers” beside her, columnist Dorothy Thompson is pictured still seated, just before being escorted out after laughing and heckling a Nazi speaker. Police later allowed her to return.

(AP Photo.)

It Can Happen Here 8

Columnist Dorothy Thompson of The New York Herald Tribune (and wife of novelist Sinclair Lewis, the author of It Can’t Happen Here), was escorted out of the rally by two New York City police officers and a Bund storm trooper after she laughed mockingly when Kunze said the Aryan race follows the Golden Rule while Jews only follow the ‘rule of gold’ (approx 1:16:50). Thompson was allowed to return after it became clear she was there as a member of the press. Nevertheless, Thompson called Americans ‘saps’ for allowing such rallies and wrote:

I saw an exact duplicate of it in the Berlin Sports Palast in 1931. That meeting was also ‘protected’ by the police of the German Republic. Three years later the people who had been in charge of that meeting were in charge of the Government of Germany, and the German citizens against whom, in 1931, exactly the same statements had been made as were made by Mr. Kunze, were being beaten, expropriated and murdered… Whenever he made one of his blanket indictments against all Americans not purely Aryan, the audience applauded and howled with joy. Between Mr. Kunze’s speech and a wholesale pogrom is a very short step…I laughed because I wanted to demonstrate how perfectly absurd all this defense of ‘free speech’ is, in connection with movements and organizations like this one.9

Religious and other groups had, in fact, petitioned New York Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, an outspoken anti-fascist, to ban the rally. A few days before the scheduled event the Mayor suggested featuring Hitler in a chamber of horrors at the World’s Fair but said that he wouldn’t stop the gathering. He told reporters, “I would then be doing exactly what Hitler is doing in carrying on his abhorrent form of government.”10

German-American Bund leader Fritz Kuhn at the Madison Square Garden rally in 1939.

(National Archives/Wikimedia Commons)

The Banality of Evil 11

With the U.S. entry into World War II the German-American Bund was disbanded and the leaders who spoke at the rally did not fare well. The German-born Fritz Kuhn (the last speaker) was found guilty of tax evasion and embezzling more than $14,000 from the Bund. He was sent to Sing Sing prison for two-and-a-half years. While there his citizenship was revoked on the grounds it had been obtained falsely. He was then rearrested for being an enemy agent and interned at a camp in Texas until the end of World War II when he was deported to Germany. He died in obscurity in 1951.

Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze at the Madison Square Garden Rally in 1939.

(National Archives/Wikimedia Commons)

Bund publicity director Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze succeeded Fritz Kuhn as head of the organization. He reportedly provided the New York District Attorney with the financial documents needed to prosecute Kuhn. After the U.S. entry into World War II, Kunze fled to Mexico with the intention of making his way to Germany but was arrested and extradited to the United States, where he was prosecuted and sent to prison for espionage and violating the Selective Service Act.

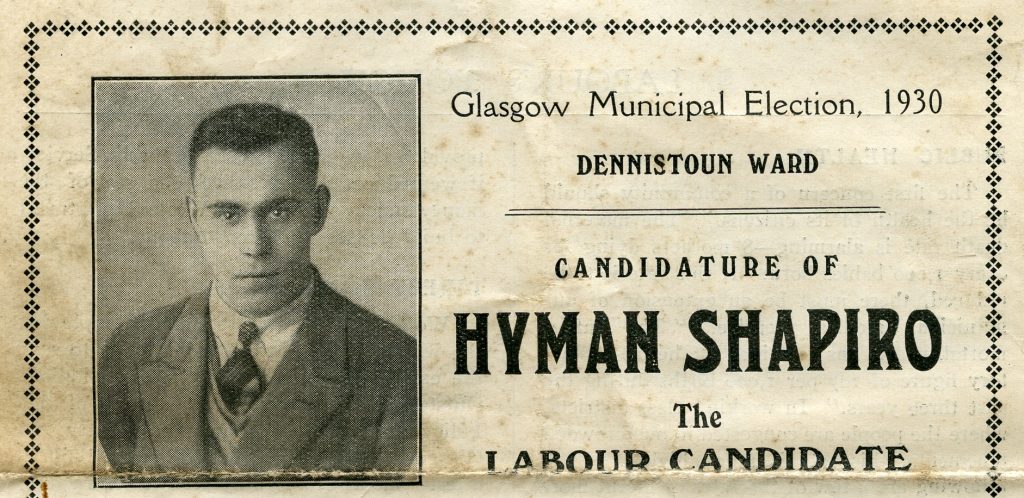

James Wheeler-Hill, National Secretary for the Bund.

(Daily News clipping)

Bund national secretary James Wheeler-Hill was described by the Daily News as “the boy orator of the Bund.” He opened the rally and acted as emcee. Wheeler-Hill resigned his post in January 1940 following his arrest for falsely claiming he was an American citizen. A Russian-born (Latvian) national, Wheeler-Hill was convicted and went to prison for a year on Welfare Island. In March 1942 he was interned as an enemy alien by the FBI and may have been deported after the war. This is unconfirmed. His brother Axel was sentenced to 16 years in prison for being a Nazi spy.

Isolationist Pastor Sigmund G. Von Bosse was the rally’s second speaker. Described by the Daily Worker as “a frequent headliner at Philadelphia Nazi rallies,” Von Bosse was, in fact, a clergyman, heading up the Bethanien Lutheran Church of Roxborough, Pennsylvania from 1934-1941. According to an obituary in The Morning News of Wilmington, Delaware, Von Bosse then went into seclusion. It reported his death in Miami Beach, Florida on November 29, 1958.

Russell J. Dunn was the third speaker. Dunn was a founder of the Catholic Common Cause League and was involved with the founding of the Flatbush Anti-Communist League. He spoke often for the Bund and the Christian Front and had ties to the American Nationalist Party. No other information is available at this time.

The German-born Rudolph Markmann was the fourth speaker. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1933. He led the Atlantic Coast District of the Bund. He was one of eight Bund leaders whose citizenship was revoked in June 1944 on the grounds he violated his citizenship oath by joining the Bund. The Brooklyn Eagle reported (March 21, 1944) that Markmann testified in Brooklyn Federal Court that he eventually quit the Bund’s many activities because it interfered with his family life and made him “tired and sleepy.” It’s not clear if Markmann was ever deported.

A Bund color guard as it marched in Madison Square Garden are saluted by followers on February 20, 1939.

(AP Photo courtesy of The New York Times)

Closing Thoughts

After listening to two hours of raw audio and then watching Marshall Curry’s six minutes of archive footage, it’s almost as if there were two different rallies. Missing from the audio is all of the pageantry and choreography that went into making it a spectacle. Add to that, the earnest looks, the storm trooper uniforms, and the Nazi salutes. Sure, we hear the crowd roar its approval at what is said, but seeing it, even for a moment, is so much more powerful. Perhaps, this is because it now seems so bizarre, I can’t begin to imagine it in my mind’s eye.

From a strictly audio perspective, as rallies go, this one had some pretty boring stretches. Kunze was the most dynamic if not rabid of the speakers while Kuhn’s revisionist history, though ponderous and tedious, made him, perhaps, the most dangerous. Still, what is remarkable is that their organization was able to muster 20,000 like-minded true believers to fill Madison Square Garden in the name of George Washington and white Christian nationalism. Add to that those around the country who agreed with them but couldn’t make the trip and we’re talking about a significant number. As filmmaker Curry says:

It’s scary and embarrassing. It tells a story about our country that we’d prefer to forget. We’d like to think that when Nazism rose up, all Americans were instantly appalled. But while the vast majority of Americans were appalled by the Nazis, there was also a significant group of Americans who were sympathetic to their white supremacist, anti-Semitic message.

Eighty years have passed. For some, however, the language and attitudes of that time and place have not faded. Indeed, the ideas and beliefs never really left. It’s as if they were a person that went into hiding, kept below the radar and out of sight, waiting patiently for an opportunity to come out into the open. It seems that opportunity has arrived. Some of the persons and groups attacked have changed along with the circumstances, but contemporary discourse and events, sadly, have some eerie echoes from that night at the Garden.

____________________________________

[1] There are a few gaps in the original recording, not necessarily due to an effort to censor or omit material, but simply because that material was missing from the original recordings done on a series of instantaneous lacquer coated aluminum discs. Based on the original event program, what appears to be missing here is the music and singing.

[2] The notion of a global conspiracy by rich and powerful Jews is hardly new. Members of the German-American Bund were no doubt inspired, at least in part, by The Elders of the Protocols of Zion a late 19th century anti-Semitic tract published in Russia that purports to be the minutes of meetings held by Jews plotting to take control the world. Although a proven forgery, it was published and widely distributed in the United States in the 1920s by auto magnate Henry Ford through his weekly newspaper, The Dearborn Independent.

[3] 22,000 Nazis Hold Rally in Garden; Police Check Foes, The New York Times, February, 21, 1939, pg.1. This contrasts with The Albany Times Union front page headline the next day proclaiming: “RIOTS AT N.Y. BUND MEETING 100,000 Jam Area as Army of Police Quells Outbreaks.”

[4] “Army of Police Cuts Bund Rally Casulties to Only a Few Injured,” The Brooklyn Eagle, February 21, 1939, pg.3. But did any of the injured include the 13 Nazis who attacked Joseph L. Greenstein, a.k.a. The Mighty Atom, who ripped down a Nazi banner outside the Garden? It may never be known, but you can listen to Greenstein’s story by Nate DiMeo following the Radio Diaries piece at: When Nazis Took Manhattan or go directly to: The Year Hank Greenberg Hit 58 Home Runs.

[5] Ibid., The New York Times.

[6] “Nazi Rally Hails Hoover’s Foreign Policy,” Daily Worker, February 21, 1939, pg. 1

[7] Ibid, pg. 4.

[8] This refers to the Sinclair Lewis’ novel It Can’t Happen Here, a political satire describing the election of ‘patriotic’ demagogue to presidency and his Nazi-like take over of the country. This is also the same pitch line filmmaker Marshall Curry used to advertise his documentary on Fox News. The network, however, refused to air the ad as written, calling it “inappropriate.” See: Hollywood Reporter.

[9] Thompson, Dorothy, “Miss Thompson Issues Statement on Bund Rally,” The New York Herald Tribune, February 21, 1939, pg. 3.

[10] “La Guardia Lets Bund Hold Rally,” The Daily News, February 18, 1939, pg. 3.

[11] This phrase refers to Hannah Arendt’s description of Adolph Eichmann at his 1962 trial in Israel. Eichmann was the Nazis’ chief architect of the genocidal ‘final solution’ for the Jews of Europe. In Arendt’s 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, she writes about the ‘normalization of wickedness’. In this regard, I highly recommend reading a piece by writer Maria Popova.

Special thanks to Andrew Golis, Jim Schachter, Joe Richman, Sarah Kramer, Marshall Curry, Ben Goldberg and Lorne Bair.

Wearing the shirt which storm troopers ripped when he interrupted a speech given by Bund leader Fritz Kuhn, anti-Nazi protester Isadore Greenbaum is reunited with his wife and son after his ordeal, February 20, 1939.

(AP Photo courtesy of The New York Times)