“…concerning Bill’s College. I believe I could study better at home, than here. Your son, E. S. Snell.”

In this post – part three of the Snell family on the installment plan (parts one and two here and here) – two letters from Ebenezer Strong Snell, Amherst College’s first student, give us a personal account of key moments in Amherst’s early history: President Zephaniah Swift Moore’s move to Amherst in 1821, and the obtaining of the charter in 1825.

The first letter, dated June 1821, is from the end of Snell’s junior year at Williams College. Written a few days after Moore announced his intention to leave Williams, Snell describes the turmoil that ensued. Even before Moore’s departure, Williams had been unsettled over the question of whether, primarily because of its remote location, it should move to Hampshire County. In fact, Moore is said to have assumed Williams would move before he accepted the presidency there and then announced his support in his inauguration speech in 1815 — what an uproar that must’ve caused. But while no one should’ve been too surprised when Moore announced shortly before the 1821 commencement that he would leave Williams for Amherst, it was still a traumatic event for those tied to the institution.¹ To some it seemed that with Moore’s exit the college might fail. What then would Williams College degrees be worth, the students wondered.

The first letter, dated June 1821, is from the end of Snell’s junior year at Williams College. Written a few days after Moore announced his intention to leave Williams, Snell describes the turmoil that ensued. Even before Moore’s departure, Williams had been unsettled over the question of whether, primarily because of its remote location, it should move to Hampshire County. In fact, Moore is said to have assumed Williams would move before he accepted the presidency there and then announced his support in his inauguration speech in 1815 — what an uproar that must’ve caused. But while no one should’ve been too surprised when Moore announced shortly before the 1821 commencement that he would leave Williams for Amherst, it was still a traumatic event for those tied to the institution.¹ To some it seemed that with Moore’s exit the college might fail. What then would Williams College degrees be worth, the students wondered.

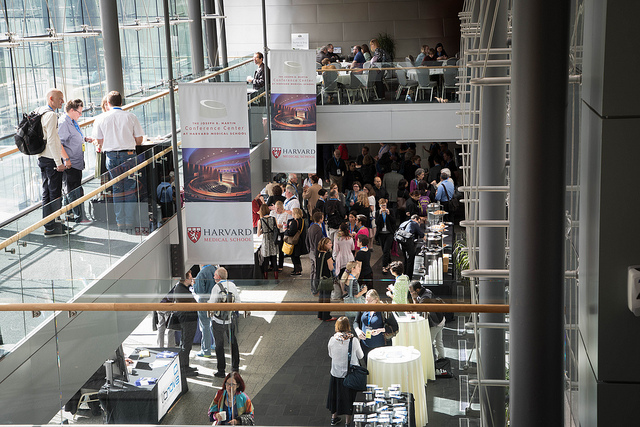

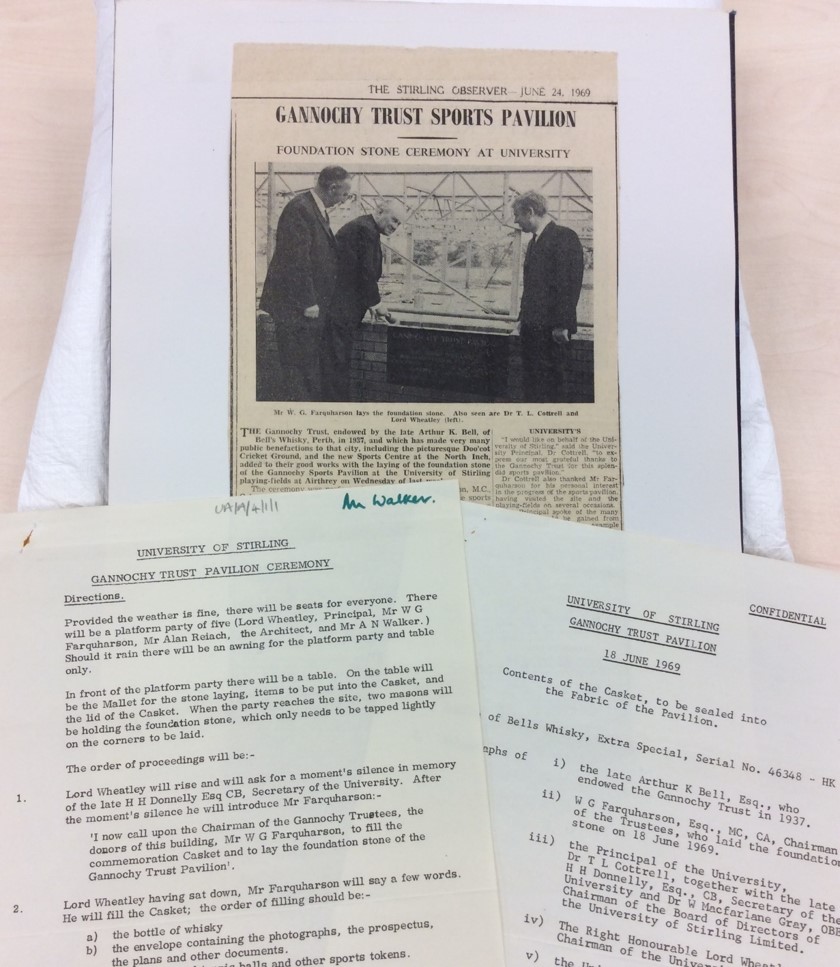

North Brookfield (bottom right), Amherst (center), and Williamstown (top left). Snell’s route between home and college probably took him through Plainfield. “Map of Massachusetts,” by H.C. Carey (1822). From the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

From a geographical perspective, moving Williams to Hampshire County (whether to Northampton or Amherst) would’ve brought Strong Snell quite a bit closer to his family in North Brookfield. More importantly, Snell’s family had longstanding ties with Moore, so their allegiance probably lay entirely with the president and his stated desire to move the college. When Moore actually left Williams, Snell was one of the 15 students who accompanied him.

Strong Snell’s 1821 letter is addressed on the outside to his father and folded like a puzzle so that it opens to one letter containing a second folded and sealed page. The first letter, addressed to “Dear Friends” is carefree and casual–actually, it’s boring. It assumes that Rev. Thomas Snell, as addressee, would open the letter and read it aloud, for on the side it has a single line that names its intended audience: “You must consider this as addressed to the whole family.” Think of the Snells gathered in the parlor to hear Rev. Snell read this letter. The family must’ve thought everything was just fine way up there at Bill’s College. Transcription below images.

Rev.d Thomas Snell., North Brookfield, Mass.

Williams College June 21 1821

Dear Friends,

I expect an opportunity to send to Brookfield tomorrow, though I know not, by whom. Some one passed College this afternoon, and left word with a student, that if I wished to send home, he would oblige me within one or two days. I have not been able to conjecture, who it was; and am very sorry that I could not be called soon enough to see the person. I was before expecting to write in a short time, and to give you an account of my journey, which was too agreeable not to be mentioned. The pleasantness of the season, and of those days in particular, with other circumstances, rendered my ride most delightful. Not perplexed with the usual cares of travelling, I could enjoy the whole scenery, that might come into view, or, by interesting conversation, forget my situation, and imagine myself in the south-west chamber; so that the stage seemed to me, as to [Prince] lee-Boo, a little house, drawn off by horses.² I arrived [in] Northampton about [8?] o’clock in the evening, and started for Wmstown at 4 in the morning; the fields of waving grain looked more beautiful than I can express; the air was fresh and cool; and the early songsters of the grove almost charmed me, as I was hurried over the level shore of the Connecticut. The huge mountains, that fill up the road towards the end of my tour, appeared far less tedious than usual. In short, I never enjoyed a journey as I did this. Esq. Noble’s daughters, returning from Boston, were my company from Northampton to Wmstown. I was but little fatigued, and was able to commence study within two hours after my arrival. I hope to hear soon, that the family are better, than when I left home. Please to remember me with esteem to the Miss Bigelows and Mercy [T.]—-. From your son and Brother, E.S. Snell.

[sideways:] You must consider this as addressed to the whole family.

The second page, intended only for his dad, is where the truth comes out:

This part of the letter I fold and seal by itself, that if you wish you may cut it out and let the other part be seen.

Williams College. June 21

Two or three days ago, the President announced to the students that he had received and accepted an appointment at Amherst; that he should resign his office in College after the next commencement; that as long as he staid here, he should feel the same interest in us, as students, that he always had done, and hoped that none would be so troubled about these circumstances, as to cause any interruption of the usual order. But his wishes & expectations, I fear, will all be scattered to the winds, if I should judge from the present movements within these brick walls.

The Class meetings of the Seniors, I would presume, would average one per day for a week past. And most of their consultations appear to be upon the subject of graduating, &c &c. of the like kind. Ten of the class have bound themselves, that on no condition whatever will they ever graduate in [W.] College. Six more have also bound themselves (before they knew the determination of the ten) that, if the ten came to the conclusion above-mentioned, they would never graduate here. As things now stand, I have no doubt that the Commencement is entirely broken up. Every thing is hilter-kilter; reports fly about the town, to & fro, quicker, as I should think, than the birds could carry them. Every body is full of suspicions. The black wood-cutters and ragged strawberry-pedlars, as they fear the loss of the grand source of their revenue, appear to take as great an interest in the matter as any one. Dr. Moore and the Students are the common subjects of talk in College or town. Destruction, ruin, death and oblivion are the predictions of most of the students concerning Bill’s College.

I believe I could study better at home, than here. Your son, E.S. Snell.

Things got better for Williams College after the arrival of the new president, Edward Dorr Griffin (the third person to be offered the position), who slid into place at noon during Commencement. Williams had endured years of uncertainty and come through it in one piece, and it would remain “in the valley of the Hoosac, one of the handsomest valleys in the world.” And Amherst College was open and operating. But Williams could give degrees – Amherst couldn’t. It didn’t have a charter from the state legislature allowing it to do so, and that was to remain a sticking point for several years. In the meantime, Amherst gave certificates. Rain checks. IOUs. A graduate was “deserving of the title and degree of Bachelor of Arts,”³ but he wasn’t getting either one. Now it was Amherst’s turn to worry about the value of its degrees, or non-degrees.

The town, the students, and the faculty had invested a lot in the promise of Amherst College, emotionally, physically, and financially. Regional newspapers followed the struggle with the state legislature for the charter, and it wasn’t at all clear to readers that Amherst would triumph. There were enough powerful opposing interests to make it a hard contest. In the end, the vote in the House was 114 to 95.4

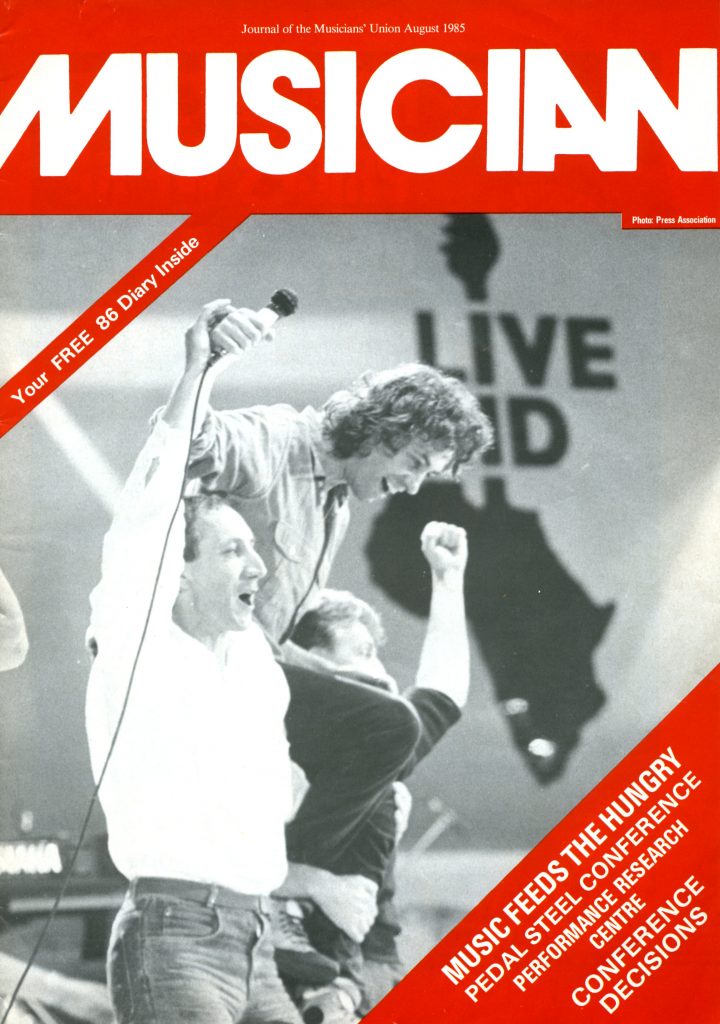

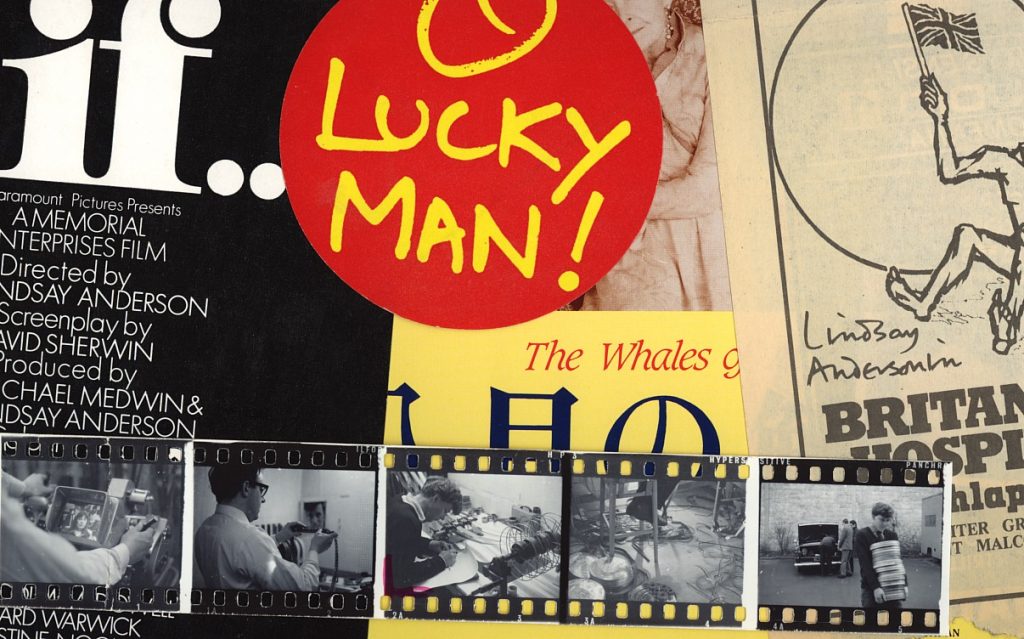

There are of course no photographs from this period, but there are photographs from the 1946 Amherst College Masquers production of Curtis Canfield’s play, “the Seed and the Sowers,” and one scene examines the fight in the legislature (click on image for gallery):

By the time the charter was finally granted in 1825, people who had sweated through the ordeal were ready to celebrate. Strong’s letter of February 23rd captures the moment of Humphrey’s return from Boston with the charter the day before, when a crowd turned out to greet him and see the document. Strong happened to have caught the stage home with Humphrey and others, so he had a first-person view of the event.

People familiar with the history of Amherst College will note that Strong misdated his letter by two years — he wrote “1823” — but there is no doubt that the charter was granted in 1825, and that Humphrey, whom Snell refers to as President (“Prest“), didn’t assume that position until later in 1823, after the death of President Moore in June of that year. It’s bizarre that Snell misdated the letter in this way — one can only speculate about how it happened — but there seems no doubt. In the transcription that follows the images of the original, I kept his date but noted that it was in error.

Amherst. Feby. 23—1823– [sic]

Dear Mother,

I stopped into the stage at N. Braintree about half past one with very agreeable company. In the first place, there were Prest Humphrey and Mr. Austin Dickinson, who came and took dinner at Mr. Fiske’s while the stages were changing and other passengers taken in. Then Miss Mary Jocelyn (if I have spelled it right) and her Brother going to Enfield. Mr. Barr, the singer, going to Greenwich, three students, coming here to the Academy; and one man unknown to me. As you see I met a larger party of acquaintance than I often do in Brookfield or Amherst. The President seemed to be in very good spirits, and very soon after he had come into Mr. Fiske’s informed us that he had the charter in [his] pocket, and that it might be seen in the next [Recorder]. But he regretted that the house thought fit to sacrifice two of the most active Trustees as a peace-offering to the opposition. Mr. [Nathan] Fiske and Esq. [John] Smith were removed from the board.5 The President told Mrs. Fiske to congratulate her husband on being dismissed in so good company and on receiving what might be esteemed so signal an honor, since all would understand that they were removed on account of having so faithfully served the interests of the Institution. The inhabitants of the village here were on the “tiptoe of expectancy” when the stage-horn sounded. The front of Mr. Boltwood’s tavern was blackened with the crowd of anxious spectators, waiting to see who had come and what news the passengers had brought. The horses had not stopped before Edward and James were thrusting in their heads and shaking hands with their father. Edward asks “have you got the Charter?” The Pres. answered in the affirmative. James, half way between laughing and crying, says “O-h-h-h! you wouldn’t come without that.” The joyful report flew quick through the throng, and when I alighted one broad smile was resting on all their countenances. Soon I felt them pressing by me into the house, to hear the charter read by Mr. [Austin] Dickinson, who had a copy of it with him. But I felt not at all inclined to follow. More than half sick with riding, I thought a feather bed would do me more good than all the chartered colleges in the union.

President Heman Humphrey brings the charter home: “Men of Amherst! We are at long last a chartered college.” (From the 1946 production of “the Seed and the Sowers”).

We have not made out much today. Every body’s attention is taken up with the celebration of the afternoon and evening. I have come near jumping out of my seat repeatedly in the school-room at the report of the cannon. And now (8 o’clock in the evening) the people are expressing their joy by firing cannon, ringing bells, and illuminating College[s] and Academy. A committee was sent by the townsmen to the President this morning to consult him respecting the expediency of doing all this. He said he should not advise it, but would not object, if the people were desirous of making a celebration. If I had been consulted, I should have expressed the same sentiment—at least the former part of it. Now it seems rather strange to me, that the populace are not willing to concur in the opinion of the two principal men in town. At 9 o’clock, subscribers from the neighborhood (I know not who,) will take supper at the Mansion House, when 17 reports will be heard from the cannon, in honor (I suppose) of the 17 Trustees. Many respectable gentlemen in town are helping on this business, but it looks to me too much like boys’ play. I cannot relish it in the connection in which I must view it – if it were on some military occasion, I should enjoy the roar of the field-piece, & the brilliancy of the illumination, but I can now express my joy better by writing home.

I have been in to see Mrs. Moore [Phebe Moore, widow of Pres. Moore]—find her nearly as well as before she was taken sick. She and Miss Cary send much love. Dr. Humphrey’s youngest children are considerably unwell; their hired girl very sick. Illness is quite prevalent in town.

24—I find I received a wrong impression respecting the supper last night. I supposed it would be attended only by part of the College students and some young towns-people who wished to have a high. But I afterward heard that it was attended by a regular and respectable, as well as numerous collection. About 100 were present, consisting of the Prest. and all the other faculty of college, college students, and inhabitants of both east and west streets. Mr. Heath had previously asked me and Mr. Paine [Elijah Paine, Class of 1823] to attend but could not tell us who would be present. We laughed at the idea of being at the tavern with a toasting company at [9] or 10 at night, and receiving no further invitation, we staid at home about our business. It is possible we may be thought rather odd, but that will never trouble us.

Professor Estabrook returned last evening. He is about to take his wife and child and remove 700 miles to the south, into Virginia, the name of the town I have not heard. He has engaged a private school and is expecting to superintend an Academy for a very handsome salary. We have 40 students in today. I feel rather more “like work” than I did yesterday, or when I left home. I am called away to school and must put what I have written into the office.

Let the first one who can spend time return a letter as good, at least, as this, and as much longer as is convenient.

Your oldest boy—

Please to remember me to all the gentlemen—Father, Doctor, Brothers Thomas and William. Likewise to all the ladies—Sisters Martha, Sarah, Tirzah and Abigail, and every body else.

Newspapers all over the region echoed Snell’s description of the celebration and described the toasts he missed by being such a stickler for propriety and choosing a feather bed over the charter celebration:

How amazing is it that we have letters from the first student to enter Amherst College, and (all the more amazing) that he writes about these important early events in Amherst’s history? There are more letters in the Snell Family Papers, many of which refer to other events in Amherst College history, and all of which shed light on this large, vibrant family of Western Massachusetts.

******************************************************************

Footnotes:

1. Read more about this period at Williams College here: a_history_of_williams_college-excerpt-re-moore

2. For “Prince Lee Boo,” see “The History of Prince Lee Boo.”

3. In the entertaining little volume of chapel talks about Amherst College history called “the Seed and the Sowers,” Curtis Canfield writes about the charter problem and includes the text of one of the graduation certificates: seed and the sowers-excerpt-sm

4. See William S. Tyler’s “A History of Amherst College,” p. 151.

5. Tyler explains that these two trustees were probably removed because they were “among the active agents in the founding of the College, and as such, particularly obnoxious to its enemies.” Snell doesn’t mention the third trustee who merited removal, Rev. Experience Porter. Ibid, 153.