If you follow this blog –and you should– then you know that Amherst has a lot of collections from missionary families. Because I work with these collections a lot, especially in arranging and describing new ones, I’ve settled into a comfortable theory about how the work of missionaries changed over the decades and generations. I notice a first generation of “strict missionaries” whose goal is first and foremost to spread the gospel. Their children, often born and raised abroad, speak two or three languages, and they know their parents’ work and where it succeeded and where it failed. They’re still usually missionaries working for the American Board, but their work often branches into teaching at primary and middle-school levels, or working in a medical clinic. A third generation is even more removed from the original mission work and its members become professors or doctors. Fourth and fifth generations might see some diplomats, government professionals, and journalists. The shift feels linear. But I always knew this way of thinking was a broad generalization, and too comfortable. I knew there would be someone to rock the boat, to mess with my theory — to zig where so many seemed to zag.

The Williams-Chambers-Seelye-Franck Family Papers (the “Franck Papers,” to be succinct but less accurate) contain an unexpected and substantial section of papers from Kate and Laurens Seelye’s daughter Mary-Averett Seelye, a professional dancer whose particular interest was what she termed “poetry in dance.” Seelye was careful to explain that she didn’t dance to poetry, she danced poetry – she danced a poem. It wasn’t an easy concept for some audiences to understand – reviews and articles show repeated explanation.

Seelye seems to have had an eye to her archives fairly early on: her papers make it possible to follow her career from start to finish, and include over 65 years of documentation illustrating the determination and hard work she put into that career. It contains correspondence, photographs, publicity materials, reviews, interviews, an audio recording of a performance, and one film.

Mary-Averett Seelye was born in New Jersey but her family moved to Beirut (then in Syria) when she was only a few months old. For one of the many résumés in the collection, Seelye made notes describing her childhood in a way that captures the years that formed her character and provided inspiration for her work:

Mary-Averett Seelye grew up in Beirut, Lebanon, where father taught; mother was active in voluntary women’s organizations. Grandparents occupied a top floor apartment. Turkish, French, Arabic filled the air. She attended an American school, summered under olive trees overlooking the Mediterranean; mosquito netting; jackal howls. Community-all-ages-baseball every Saturday afternoon provided public measure of the youngsters’ developing prowess to catch a fly and hit a homer. Parents loved to dance. Father taught daughters. Daughters taught brother. Easter holidays took the family to Palmyra, Jerusalem, Cairo, Damascus. Part of an ethnic minority–yes–but a privileged one in which occupations were to learn and discover, educate, provide medical, spiritual, and economic help and “live in international brotherhood.”*

The Chambers-Seelye clan in Adana, Turkey, about 1922. Back row: Laurens H. Seelye (AC 1911); Kate Chambers Seelye; Dorothea Chambers holding her niece Dorothea Seelye; William Nesbitt Chambers. Seated: Cornelia Williams Chambers and her granddaughter Mary-Averett Seelye.

Seelye’s notes go on to record the family’s furlough in the United States that became permanent for Mary-Averett. New England replaced the Middle East as home. Seelye attended Bennington College in Vermont, where she studied drama. In the winter of 1940, she formed the “Trio Theatre” with Carolyn Gerber and Molly Howe, two fellow graduates from Bennington. The group performed”pieces incorporating movement and words,” including their version of Abel Meeropol’s “Strange Fruit.” Seelye then went to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for her M.A., which she received in 1944.

Mary-Averett Seelye (at left), ca. 1943, with an unspecified member of the Trio Theatre at the Forest Theatre, located on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In 1949 she formed the Theatre Lobby with Mary Goldwater and worked as its production director for nine years. The Theatre Lobby was a “pocket theatre” located in an old carriage house in the mews behind St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington, D.C. The cast performed classic and modern works and was interracial at a time when other Washington theatres weren’t. Seelye’s last work as director for the theater was Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” in 1959. The collection contains a note from Beckett to Seelye congratulating her on her work. (Click on images for gallery.)

By the 1960s Seelye’s interest had turned increasingly to solo performances, specifically the concept of poetry-in-dance. It was work that had grown out of her studies in drama and dance at Bennington College and that she had performed early on, then intermittently during the Theatre Lobby years, and then again — under the title of “Poetry-in-Dance”– beginning in 1957. She would perform “Poetry-in-Dance” regularly through the 1960s and 70s. Georgetown University’s Donn B. Murphy wrote a short memoir about Seelye in which he described the work that gathered momentum in this period:

Although American choreographers worked with words as early as Martha Graham’s American Document in 1938, Ms. Seelye was virtually alone in the continuity of her work in this mode, and in the individuality of her performances, presented over a period of more than thirty years. She was noted for choosing exceptionally challenging literature and joining it with a movement idiom which is more often abstract than illustrative…

Extremely tall and thin, Ms. Seelye’s striking physical presence onstage was enhanced by minimal sculptural forms, carefully imagined costumes, and arresting lighting effects. Though her works sometimes used music composed by Stephen Bates and Jutta Eigen, they were more characteristically performed to the sound of her voice alone. She moved around, on top of, and through the sculptural pieces…

Investigating several cultures through personally devised visions in motion, Seelye was an actress-choreographer-dancer linked both with the earliest performers of antiquity, and the latest creators of avant-garde.”*

(Click for gallery.)

In 1972 she formed Kinesis, a logical extension of Poetry-in-Dance. She continued to dance into her late 70s. (Click for gallery.)

Of course, Seelye never forgot her youth in the Middle East. Her way of remaining connected to the family’s roots there included a trip in the 1980s to perform in Beirut and Istanbul. She also used Turkish and Arabic poetry in her repertoire in the United States.

Seelye’s papers indicate that she had some concern that her particular brand of dance might die with her if she didn’t take care to document her work. Toward the end of her career she began to work with videographer Vin Grabill to film some of her performances. The result was a three-DVD collection of Seelye’s work, as well as a smaller film, “Poetry Moves,” featuring Seelye’s work with poet Josephine Jacobsen. Seelye and Jacobsen collaborated for many years, and some of their correspondence is in the collection. Clips of Seelye’s later performances may be seen at Vin Grabill’s Vimeo site, here.

***************************************************************

Franck Papers, Box 14, Folder 1: Resumes and other biographical documents.

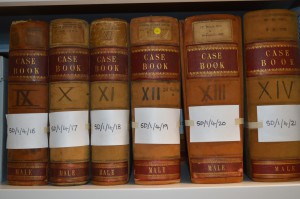

Kenneth Brown’s daughter Edith turned 15 in 1876 and a “Miss Brown” is recorded in the Occurrence Book as visiting with Kenneth’s mother “Mrs Brown” on 6 March. On 1 April it states “visited by Miss E Brown (private) Sheriff’s order”, so she visited alone. Again she is listed as visiting with “Master C Brown” on 15 May. On several other occasions relatives and friends are recorded as visiting with “2 children”. The day before Kenneth Brown is executed, “Mr M Brown and 4 children” visit the condemned cell at 4.15pm. Kenneth Brown had four surviving children with his first wife Mary Eliza Dircksey nee Wittenoom (a daughter of WA’s first colonial chaplain Rev. J.B. Wittenoom). It was a busy afternoon as Mr Parker had visited at 3.20pm, and the Dean visited at 5.10pm. Maitland Brown visited again at 8pm followed by the Dean again at 8.15pm. This flurry of activity conveys the sense of an impending event. We can only imagine what these visits were like.

Kenneth Brown’s daughter Edith turned 15 in 1876 and a “Miss Brown” is recorded in the Occurrence Book as visiting with Kenneth’s mother “Mrs Brown” on 6 March. On 1 April it states “visited by Miss E Brown (private) Sheriff’s order”, so she visited alone. Again she is listed as visiting with “Master C Brown” on 15 May. On several other occasions relatives and friends are recorded as visiting with “2 children”. The day before Kenneth Brown is executed, “Mr M Brown and 4 children” visit the condemned cell at 4.15pm. Kenneth Brown had four surviving children with his first wife Mary Eliza Dircksey nee Wittenoom (a daughter of WA’s first colonial chaplain Rev. J.B. Wittenoom). It was a busy afternoon as Mr Parker had visited at 3.20pm, and the Dean visited at 5.10pm. Maitland Brown visited again at 8pm followed by the Dean again at 8.15pm. This flurry of activity conveys the sense of an impending event. We can only imagine what these visits were like.