Sidney Brooks letter to his sister Tamesin Brooks, October 18, 1837, second page top: “The room which I occupy in College is rather a dismal looking place, as the freshmen are put into the poorest rooms. It made me think of the rooms in Barnstable jail, but this is College Style.”

Born in Harwich, in Barnstable County on Cape Cod, Sidney Brooks attended Amherst College after preparation at Chatham Academy and at Phillips Academy in Andover. After graduating and teaching for a few years at Chatham, he went on to build Pine Grove Seminary, the first secondary school in Harwich. The building was the future site of Harwich High School, and today it houses the Harwich Historical Society.

The Sidney Brooks (AC 1841) Papers, comprised largely of correspondence and other writing from his school days, provides an intimate portrait of a middling student from the nation’s nascent middle class. Sidney wrote to his siblings of his daily routines and to his father about money, and he kept a detailed ledger of his expenses in Amherst. Financially dependent on his father, the merchant Obed Brooks of Harwich, Sidney wrote home in a tone perhaps recognizable to indigent college students throughout the ages.

In a painstaking account in a letter to his father of June 28, 1838, Sidney writes of his expenses at Philips Academy and Amherst College, underlined section page 2 bottom: “if I had, of my own, money or property enough to give me a liberal education and no more, I should not hesitate at all to spend it in this way.”

The letter above was likely compiled from a detailed ledger kept by Brooks during his time at Andover and Amherst. In the ledger, he records his expenses for each term. Tuition, boarding and school related fees make up the bulk of his expenses.

Sidney Brooks’ school expenses ledger, 1837-1841.

A member of the Athenian Society, one of Amherst’s rival literary clubs, Sidney records the group’s initiation fee in 1838 as $3.00, with subsequent taxes ranging from $1.00 to $3.00 every term or so. Sidney was not the only member for whom the literary society fees might have posed some challenge, in this last decade before their dissolution and waning in the face of new campus societies and fraternities. In Student Life at Amherst College: Its Organizations, their Membership and History (1871), page 29, we find that,

As early as August, 1838, the societies began to be embarrassed financially, so that the members could with difficulty meet the current expenses and pay existing debts. Moneys received from initiation fees, which heretofore had been annually appropriated for libraries, were used to liquidate standing debts. Extensive repairs, etc., upon their Athenaeums increased their liabilities.

In addition to Sidney’s expense ledger and correspondence, the collection includes several prepared speeches on diverse subjects, presumably conducted for the various societies of which he was a part. During the reign of the Alexandrian and Athenian Societies at Amherst, weekly sessions were held for declamation and debate.

Twenty-eight years old when he graduated Amherst, Sidney arrived at the College already practiced in these activities from his time at Phillips Academy in Andover. Sidney was an enthusiastic participant in the Rhetorical Society at the Andover Theological Seminary. In 1834, at the same time Henry Ward Beecher was busy making phrenology the hot topic of Amherst’s Natural History Society, Sidney argued his case for the “science” in the less welcoming atmosphere of the Theological Seminary. (There is no evidence that Sidney was ever invited to become a member of the Natural History Society, or any secret societies, while at Amherst.)

Phrenology, a pseudoscience concerned with measurements of the surface of the head to diagnose traits of character and personality, was hugely popular in the nineteenth century and persisted through the beginning of the twentieth. In 1847, it was popular enough that Edward Hitchcock got his head examined by the professional phrenologists and Amherst alumni, brothers Orson Squire Fowler and Lorenzo Niles Fowler. In 1834, however, Orson Squire Fowler was still a senior at Amherst, along with Henry Ward Beecher, then president of the Natural History Society in its third year of operation.

Perhaps the word hadn’t yet spread to Andover: the impression given by Sidney’s speech is not one of faddish acceptance on the part of his audience. Over several drafts on the subject, Sidney hones his argument, which amounts to a plea for reasoned debate based on empirical facts over the inclination to reject the field on moralistic grounds as a danger to religion. From a rough draft of his speech at Andover:

How much the decisions of this society above mentioned have influenced your minds – or the minds of this community – I cannot tell, but certain it is all investigation and enquiry upon the subject seem to be put to sleep for the present, and ma[n]y no doubt think that it has received its death blow. But I have not introduced the subject to lament its downfall or to sing its requiem nor to renounce the belief which I have so long entertained – nor shall I until I have more efficient arguments to prove that it is dangerous to religion or it is not true.

Sidney’s writing ranges widely across subjects, but always returns to the glory of God the Creator. He records subscription fees to missionary and Bible societies, including an initiation fee and tax (only $0.37) for the Society of Inquiry, the religious society at Amherst. In one speech, his theme is, “Can a Christian consistently accept an appointment at Amherst College?” At the same time, he expounds on such subjects as the astrophysical causes of the aurora borealis and of meteors with apparent enthusiasm, if not expertise. Sidney records $1.56 as the cost of going on a geological excursion with Professor Hitchcock, and $2.00 for subscription to the student literary periodical, Horae Colleginae – the short run of which coincided with his enrollment.

If Sidney’s account ledger provides a glimpse into the spending habits of one among the “indigent young men of piety and talent” educated in the early years of Amherst College, his letters are likewise a window on the melancholic mind of a student far from home. In the spring term of 1838 Sidney switched rooms, a decision he defended in a letter to his brother of July 19:

My reasons for making this moove are several. First I believe I can study more rooming alone. Again I wanted to enjoy the sweets of solitude and I enjoy it much. I know I hurt myself rooming alone at Andover when in that state of mind I was then, but I have not been troubled at all with the melancholia since I have been alone this term. Another consideration of some importance induced me to come down into a lower room — I have always been given somewhat to somnambulism. It has grown upon me much of late, for several weekes, nearly every night, I find myself in the middle of the night, in some part of my bedroom. Sometimes in bed + sometimes out of it pawing around to find out where I was. I thought I might find myself sometime in the act of jumping out of the window–

Rooming alone may have hurt Sidney at Amherst as much as it did at Andover, as he fell ill in the fall of his sophomore year. In a letter to his father of December 20, 1838, Sidney writes of his recovery from illness, “I ought to be very thankful and trust I am that I am restored to health again at any cost. (It would become me better perhaps to say this though if the money which is to defray this cost were my own.)” His sister Harriet visited and tended to him, inflating his bills for room and board considerably. Writing to his father the next spring (April 23, 1839), Sidney reports that Squire Dickinson has declined to deduct any of his college bill for the period of his illness. “If this is the custom,” he writes, “I suppose there is no getting off from it though like many other customs it seems rather hard.”

Sidney Brooks to his father Obed Brooks, April 23, 1839, first page middle: “If this is the custom I suppose there is no getting off from it though like many other customs it seems rather hard.”

In the recessed economic climate of New England following the Panic of 1837, it is little wonder Sidney found himself justifying his various expenses to his father. In a letter to his father of March 21, 1840, he grapples with trying to live frugally while taking advantage of the social opportunities of the college. After acknowledging the forty dollars he has received from home, Sidney implores his father to understand the necessity, for a young man of reputation, of indulging in a certain amount of “liberality,” a concept his father does not seem readily to understand. Describing his own place in the campus society, Sidney writes,

By no means do I rank myself among the highest class here, that class called the aristocracy. If I did I should have to do far different than I do – to carry an ivory or a silver headed cane, never to soil my hands with labor, ride about etc, etc, though among them are some no better able to do it than myself. This class is pretty numerous and popular in College, though I do not know as anyone thinks any the less of me for the plain manner in which I generally go.

Sidney Brooks letter to his father Obed Brooks, March 21, 1840, fourth page top: “It is another kind of liberality that I had principally in view- liberal towards ourselves.”

On leaving Amherst, Sidney taught for three years at Chatham Academy before returning home to Harwich and founding Pine Grove Seminary. Pine Grove, a one room schoolhouse whose columned Doric façade seems to suggest that Amherst left its mark, was notable for its nautical as well as classical curriculum. Navigation and surveying were included in its advanced mathematics class.

Sidney became an enlisting officer in 1863 for the towns of Harwich, Chatham, and Orleans, and served as a delegate of the Christian Commission during the war. While ministering to wounded Union soldiers in this role, Sidney wrote a series of letters to his sisters and his wife Susan about his experiences at military hospitals and battlegrounds. These were later edited and marked up considerably, presumably on Sidney’s suggestion to his correspondents that they get his accounts published in the local paper. In one letter dated July 21, 1864, Sidney describes to his sister Sarah the arrival of a delegation from Amherst College: one student, Professor Seelye, Professor Hitchcock (“son of my old Professor”), and Professor Tyler’s son.

Sidney Brooks to his sister Sarah, July 21, 1864, second page middle: “Among our members are three who came last night from Amherst College — one student, Prof. Selee and Prof. Hitchcock (son of my old Professor), also Prof. Tyler’s son. Prof. H. is not to commence hospital work to-day and, wanting something to do, he is now nailing up boxes of papers to go to the Front.”

After the war, Sidney sold his school to the town of Harwich in 1869, and in 1880 it became Harwich High School, the first public secondary educational facility there. Later it was called Brooks Academy, and today it houses the Harwich Historical Society. Sidney went on to work for the state, teaching aboard the ship George M Barnard in the short-lived Nautical Branch of the Massachusetts Reform School. Afterwards, he became Shipping Commissioner in Boston, where he lived until his death in 1887.

The Sidney Brooks (AC 1841) Papers are available to researchers in the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

![]()

Well, it’s been busy round here. The new rolling stacks have made a big difference to life in the archive. At last the archives are beginning to be more accessible. Thank you, School of Archaeology!

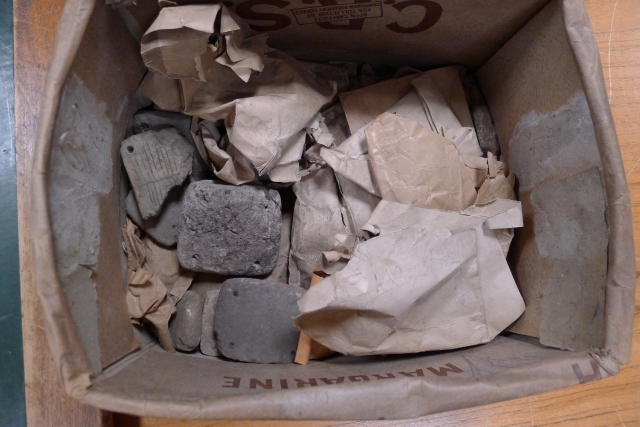

Well, it’s been busy round here. The new rolling stacks have made a big difference to life in the archive. At last the archives are beginning to be more accessible. Thank you, School of Archaeology! It isn’t too attractive at first sight, but someone had written ‘Jacquetta Hawkes? Portugal?’ on the side, so we started taking everything out of the box and found some treasures, including:

It isn’t too attractive at first sight, but someone had written ‘Jacquetta Hawkes? Portugal?’ on the side, so we started taking everything out of the box and found some treasures, including:

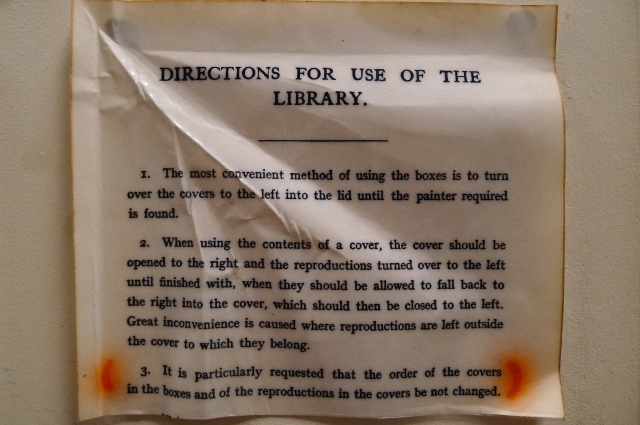

Useful advice on how to handle albums. On the subject of albums, new acquisitions include a set of books and papers..

Useful advice on how to handle albums. On the subject of albums, new acquisitions include a set of books and papers..

It’s going to be interesting researching the collection: we’ll be adding the photographs to the

It’s going to be interesting researching the collection: we’ll be adding the photographs to the

Many scholars have written about this book, a recent piece that specifically addresses Morton’s use of illustrations appeared in 2014 in the journal American Studies:

Many scholars have written about this book, a recent piece that specifically addresses Morton’s use of illustrations appeared in 2014 in the journal American Studies: