ANNOUNCER: Your city station presents Those Who Have Made Good…a series of programs organized by Clifford Burdette presenting famous Negro personalities to tell about their lives and entertain us with their talents. Each week we bring to this audience Negroes who have made a place for themselves in public life, who have risen from the most humble beginnings to attain a place of significance and consequence in the world of today. And here is Clifford Burdette, who will introduce today’s guest…[1]

Clifford Burdette’s weekly program Those Who Have Made Good premiered on WNYC on May 11, 1941, with actor Canada Lee as his first guest and musical back-up from the Juanita Hall Choir. Lee was then playing the lead in Orson Wells’ production of Native Son at Manhattan’s St. James Theatre. The actor, who had also worked with Wells in the ‘the Negro Macbeth,’ provided Burdette and WNYC listeners with a summary of his earlier career as a violinist, jockey, and prize fighter. He set the tone too for future shows by feeling at ease to discuss the need for black actors to break out of stereotypical roles and praising the work of writers Dorothy and DuBose Heyward, whose work gave African-American actors an opportunity to take on substantive roles. (Together the duo had turned DuBose’s book Porgy into the play Porgy and Bess). In reviewing the opening show Variety saw promise.

Obviously inclined to appeal to Negroes, it should nevertheless get a reasonable following from all groups on its own strength…Among the ten Negro subjects of the shows are genuinely impressive figures. If the scripts and production measure up, the program should prove inspiring.[2]

The year-long Sunday afternoon series became a veritable Who’s Who of accomplished African-Americans in 1941 and 1942. Along with Canada Lee, interviewees included: the poet Countee Cullen (audio above)[2]; the great performer and activist Paul Robeson; singer and actress Georgette Harvey; the Reverend Adam Clayton Powell; aviator James Peck; composer W.C. Handy (see photo below); folksinger, Josh White; tenor Horace R. Mann; actor and comedian Eddie Green; New York City police officer Samuel J. Battle; Bishop William J. Walls of A.M.E. Zion Church; composer, lyricist and playwright Noble Sissle; singer and actor Kenneth Lee Spencer and dancer Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson; activist Max Yergin; soprano Anne Wiggins Brown; conductor Dean Dixon; bandleader Count Basie; actors Musa Williams and Reginald Bean; and groups like The Charioteers and The Golden Gate Quartette.

Burdette’s fifth guest in June was NAACP head Walter White, who described the group as “a fighting organization” waging a long battle against lynching, with some nineteen Supreme Court victories for civil rights.[3] In August, the outspoken theater professor Owen Dodson called for a new approach to African-American drama saying, “We’ve got to choke that Mammy with her bandanna and take all those ribbons out of the pickaninnies’ hair.” Dodson also read two of his poems, The Lynching and After the Lynching, for which the progressive tabloid PM’s radio reviewer commented, “strong talk for any radio station except the uninhibited WNYC.”[4] In September, jazz singer and pianist Hazel Scott discussed her career and played an arrangement of George Gershwin’s “The Man I Love”. The New York Amsterdam News called it “the only program on the air which allows Negro artists and professional men to speak the truth about their views on conditions in America today.”[5]

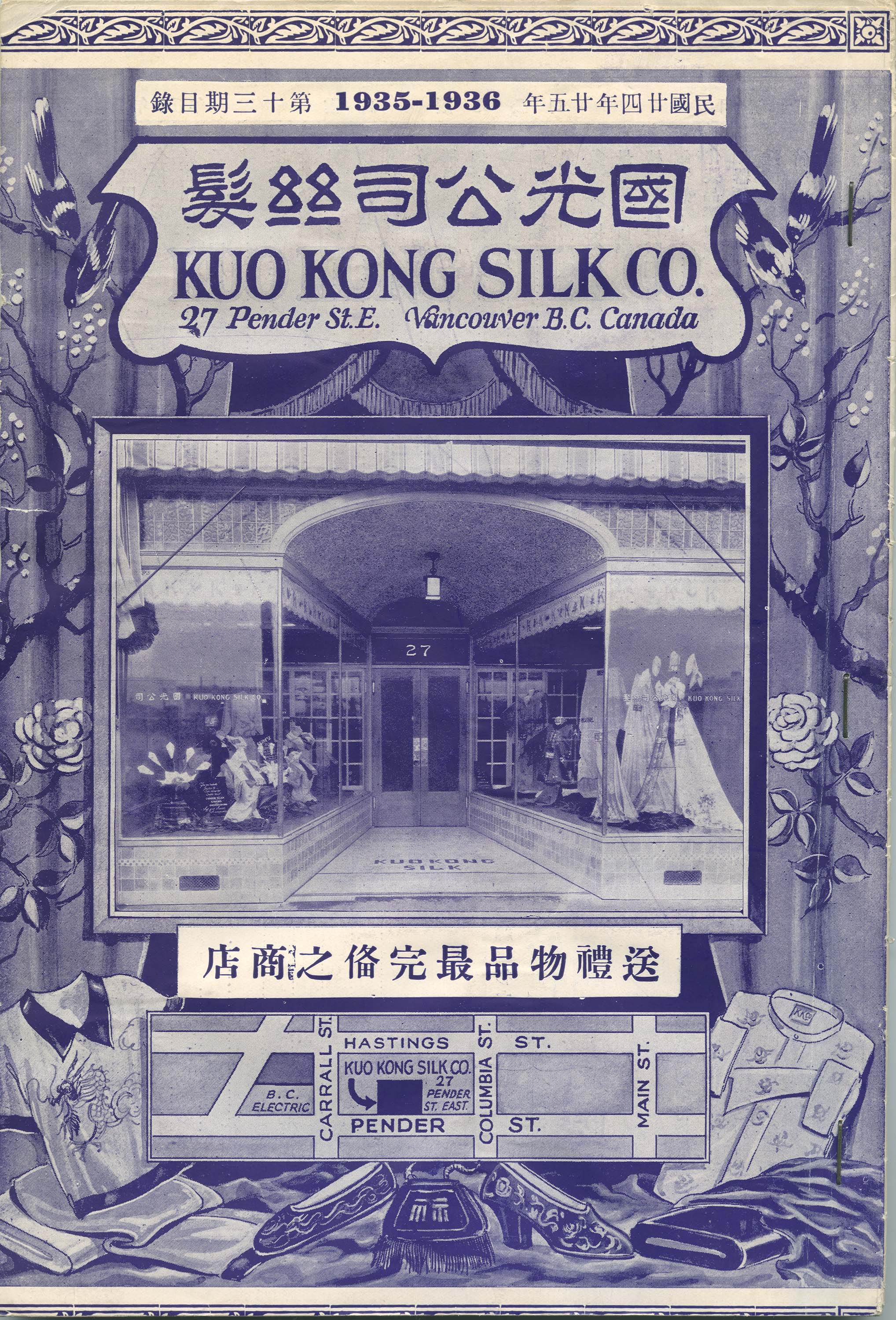

WNYC producer Clifford Burdette in Studio C with James H. Hubert, New York Secretary of the Urban League, and composer W.C. Handy (left) in 1941.

(Daily Worker/Daily World Photographs Collection, Tamiment Library, New York University)

The Sunday program, sponsored by the NAACP,[6] is among the earliest of African-American radio programs devoted to serious interview and discussion.[7] Burdette is certainly among the very earliest of black radio producers, although no studies or statistics were available until 1947, when the National Negro Congress released a damning report indicating that of the thirty thousand white collar radio jobs in the U.S., there were only two African-Americans in the position of radio director and producer. Those two, as it happens, were Bill Chase and Clifford Burdette, with WNYC’s program Freedom’s Ladder, a show focused on civil rights and race relations.[8] [9] [10]

Burdette was profiled in the January 1942 Daily Worker, the American Communist Party’s newspaper. The piece likens the 27-year-old’s story to a Horatio Alger transformation, although Burdette’s biography is more rags to respectability than rags to riches. Author James Morison quotes Burdette on radio’s early influence on his life.

During my school days in Georgia, I became the boy soprano of the school glee club, traveling over the state reciting poems based on the Negroes of the South. When I was only eight years old, I owned my own radio, buying it with the money I earned selling newspapers. It was a crystal set, but it was good enough for me to hear the voices of Paul Robeson, Roland Hayes, and other great Negro singers…

Hearing that Metropolitan Opera star Lawrence Tibbett was coming to Atlanta and wanted “a group of Negro boys to sing spirituals for him,” Burdette managed to get his glee club to sing for the renowned tenor. After high school, Burdette spent a year at Morehouse College and tried, unsuccessfully, to get a position with the WPA Theatre Project. He then worked digging ditches and selling Coca Cola to get by. Eventually, he made his way to New York and contacted Tibbett, who helped him with money and connections. He got a job as a stock clerk at a 14th Street silk store and as he tells it:

I induced WNYC to let me experiment with an interview program, and finally, the NAACP sponsored it. Today it is a popular feature with Negro and white listeners wherever WNYC is heard… My program is dedicated to the progress of the Negro people, to acquaint all of America with our achievements and to promote the cause of true democracy in the United States…[11]

By late May of 1942 Burdette had reached his fifty-fourth show at WNYC and was looking to spread his wings. He wanted to produce a radio salute to African-Americans in the armed forces using some of the celebrities he had interviewed on the station like Noble Sissle and Joe Louis. The Times wrote, “He thinks it ought to be on a national hook-up and is willing to talk it over with any interested party from a network.”[12] While it doesn’t appear he got any calls, he did start a new program on WNEW called All Men Are Created Equal. He described the thirteen-week series as ‘a powerful fight for equal rights for all people.’ Among those appearing were folksinger Josh White, band leader Cab Calloway, and the actors Canada Lee, Zero Mostel and Vincent Price. The program reportedly received a thumbs up First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt with the suggestion it be underwritten by the Office of War Information.[13] After its run at WNEW the show moved to WINS for an additional ten weeks and was sponsored by the National Negro Congress.[14] A year later, Burdette joined the production staff at WOR. That was followed by a brief stint in the Army, where he was stationed in Gulf Port, Mississippi. There he staged a production called Wings of Jive at the base camp.[15] Once he was out of the service, 1945 found him back at WNYC, where he teamed up with host Bill Chase to produce Freedom’s Ladder. In a 1946 newspaper interview Burdette described the show this way:

Our show aims to entertain and promote the idea that everyone has a chance to climb freedom’s ladder. You got to be good and you got to work at it. Canada Lee, Joe Louis and Marian Anderson did not get where they are today just because they had ability. They trained; they worked; they struggled and they got to the top.[16]

Beyond WNYC in 1947, Burdette’s life remains a mystery. If you have any information on him, please contact us.

_____________________________________________

[1] This appears to be the standard announcer introduction to the program after four months on the air. Earlier introductions spoke of the guests as overcoming “the restrictions imposed by race and environment.” Special thanks to the New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Radio Scripts Collection.

[2] Radio Reviews, Variety, May 14, 1941, pg. 32.

[3] Burdette, Clifford, Interview with Countee Cullen on Those Who Have Made Good, WNYC, June 22, 1941. A very special thanks to Brenda Flora, Archivist, and the Amistad Research Center, Tulane University for making this rare recording available to us.

[4] “Walter White Heard On Air,” The New York Amsterdam News, June 14, 1941, pg. 2.”

[5] “Strange Fruit,” PM, August 25, 1941, pg. 20.

[6] “Battle’s Story on Air Lanes,” The New York Amsterdam News, September 20, 1941, pg. 20.

[7] According to the New York daily PM, the program’s first ten weeks of expenses were paid for by the NAACP, with the following weeks covered by Burdette’s “own meager pocketbook” and many times leaving him “without food for the rest of the day.” PM, November 24, 1941.

[8] “The Negro’s Status in Radio,” 1947, papers of the National Negro Congress cited by Sonja D. Williams in Word Warrior: Richard Durham, Radio and Freedom.

[9] Those Who Have Made Good was not the NAACP’s first program on WNYC. Between November 20, 1929 and July 16, 1930 the civil rights organization had a weekly Wednesday segment of talks by prominent members. The first November program came just two and a half weeks after the premiere of WSBC Chicago’s The All-Negro Hour the first weekly radio variety show featuring African-American entertainers.

[10] On March 16, 1947, the Cultural Division of the National Negro Congress held a radio panel as part of a conference at the Murray Hill Hotel in New York to “survey the position of Negroes” in theatre, radio, screen, music, and advertising. The panel concluded, “Like many of the other institutions in America, radio takes on the segregation pattern of the community, varying from section to section, but never offering true equality of opportunity or of representation of the one-tenth of the population that the Negroes form. Actually radio fosters that pattern [and] is one of the most powerful instruments for doing so. In dramatizations and newscasts, Negroes are seldom mentioned except in the presentation of unfavorable facts out of context. Thus radio strengthens the force of those who prevent Negroes and other minority groups from getting their fair share of political, economic, and cultural equality.” Source: National Negro Congress papers, NYPL, The Negro’s Status in Radio, Summary of Radio Panel, March 1947.

[11] Morison, James,“Success and Clifford Burdette: Negro Radio Impresario at 27,” Daily Worker, January 20, 1942. Reproduced in the Encyclopedia of the Great Black Migration, edited by Steven A. Reich, Vol. 3.

[12] “One Thing and Another,” The New York Times, May 29, 1942, pg. X10.

[13] “Cliff Burdette Still Plugging,” The New York Age, October 17, 1942, pg. 5.

[14] “Clifford Burdette Gets WOR Spot,” The New York Amsterdam News, July 24, 1943, pg.20

[15] “Jottings,” The New York Amsterdam News, June 10, 1944, pg. 6B.

[16] “SCAD Official Heard on WNYC,” The Baltimore Afro-American, September 14, 1946, pg. 15.

_____________________

Thanks to WNYC Senior Archivist Marcos Sueiro Bal for his expert signal processing and production work.

![]()

On the other side of the card was a summons to a College meeting to discuss ‘the question of inoculation against influenza’:

On the other side of the card was a summons to a College meeting to discuss ‘the question of inoculation against influenza’: