The George Foster Peabody Awards are among the most prestigious awards in broadcasting. The awards “recognize distinguished achievement and meritorious public service by radio and television stations, networks, producing organizations and individuals. They perpetuate the memory of the banker-philanthropist whose name they bear. The awards program is administered by the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication of the University of Georgia, as it has been since the award’s inception in 1939. Selections are made by the Peabody Awards Board a committee of experts in media, culture, journalism, and the arts following review by special screening committees of the faculty, staff and students.”

WNYC has a proud tradition of Peabody-award winning programs dating back to 1944. WQXR’s recognition goes back to the first year the awards were given in 1940 with an Honorable Mention. Below, read the Peabody Committee’s award citations and listen to the original audio submitted for consideration. (Special thanks to Archives Director Ruta Abolins and Archivists Mary Miller and Margie Compton at the J. Walter Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection at the University of Georgia for their assistance with this page which was produced by the New York Public Radio Archives).

2015: WQXR Radio/Q2 Music

Meet the Composer

Meet the Composer is the Q2 Music podcast that takes listeners into the minds and creative processes of the composers making some of the most innovative, compelling and breathtakingly beautiful music today. The Peabody Awards committee called the series, “Fascinating, intelligent, enlightening podcasts devoted to the work of current classical composers. The show integrates music with thoughtful conversation about it without distracting from either.”

Launched in 2014, the show is hosted by critically acclaimed violist Nadia Sirota, and has delved into the minds of composers such as John Luther Adams, Caroline Shaw, Meredith Monk and Nico Muhly. Both seasons were funded in part by a successful Kickstarter campaigns. Part of WQXR, Q2 Music is a New York-based online station devoted to the music of living composers.

The Meet The Composer team: Hannis Brown, Curtis MacDonald, Alex Ambrose, Alex Overington, Carol Ann Cheung and Nadia Sirota. This is WQXR’s first Peabody Award since 1962.

Meet The Composer staff: Hannis Brown, Curtis MacDonald, Alex Ambrose, Alex Overington, Carol Ann Cheung, Nadia Sirota and Graham Parker

(WQXR Selfie Collection)

2014: WNYC Radio

Radiolab

RADIOLAB’S “60 WORDS” has garnered a second Peabody Award for Radiolab, WNYC’s popular podcast and radio program — created and produced by Jad Abumrad, co-hosted by Robert Krulwich — which first won in 2011. Produced by Radiolab’s Kelsey Padgett and Matt Kielty and reported by BuzzFeed’s Gregory Johnson, this episode pulls apart a single sentence that has led to the longest war in U.S. history. These 60 words of legal language, drafted in the hours following the September 11 attacks, continue to blur the line between war and peace. Said the Peabody Awards judges: A “Radiolab” collaboration with Buzzfeed reporter Gregory Johnsen, it takes a hard, disturbing look at the broad, malleable wording of the Authorization of Use of Military Force Act, approved by near-unanimous Congressional vote shortly after the 9/11 attacks, and how its interpretation has expanded military power and secrecy.

Radiolab’s Matt Kielty and Kelsey Padgett pose with award during The 74th Annual Peabody Awards Ceremony at Cipriani Wall Street on May 31, 2015 in New York City.

(Jemal Countess/Getty Images)

WNYC News

“CHRIS CHRISTIE, WHITE HOUSE AMBITIONS AND THE ABUSE OF POWER” has also earned WNYC a Peabody Award, its first specifically for news coverage since 1944, when WNYC won for Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s weekly addresses to the City. This series of reports, which examines the exercise of power by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie and his administration, was the work of a team of WNYC and New Jersey Public Radio reporters, producers and engineers, including Andrea Bernstein and Matt Katz. The effort was led by Nancy Solomon, managing editor of New Jersey Public Radio, and overseen by Jim Schachter, WNYC’s Vice President for News. WNYC’s sustained investigation helped establish the narrative for the local and national media’s reporting on the Christie administration’s politicization of traffic control at the busiest bridge in the world, of operations at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and of federal Sandy aid in Hoboken. These reports prompted state and federal investigations and spurred legislative reform efforts.

Said the Peabody Awards judges: “In a series of pithy news reports about the “Bridgegate” scandal, WNYC helped to link a disruptive bridge closure to a broader pattern of questionable political operations by New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie’s office. Its coverage sparked national news coverage, high-profile resignations in the Christie administration, and criminal investigations into the Port Authority.”

NJPR Reporter Scott Gurian, NJPR Managing Editor Nancy Solomon, NJPR Reporter Matt Katz, WNYC News Senior Editor for Politics and Policy Andrea Bernstein and NYPR Data News Producer Jenny Ye

( Mike Coppola/Getty Images for Peabody Awards)

2012: WNYC Radio

The Leonard Lopate Show

“For more than two decades, Leonard Lopate has quizzed and bantered live on the radio with architects and assemblymen, chefs and climatologists. With his guests he has knowledgeably and enthusiastically monitored the vital signs of New York City’s cultural and civic life. But the thing that truly sets his daily shows apart is Lopate and his producers’ knack for recognizing and explicating issues and activities that are being neglected by other media outlets despite their potential impact on the residents’ lives. In 2012, he engaged in spirited conversations about what a proposed multi-million dollar renovation and reorganization at the main branch of the New York Public Library would truly mean to its users. He analyzed the potential impact on Greenwich Village of New York University’s plans for a two-and-a-half million square foot expansion. And no one, before or after Hurricane Sandy swamped the city, did a more thorough, creative job of brainstorming how to waterproof Gotham. For considering all things New York in lively broadcasts that, like the host, value light more than heat, The Leonard Lopate Show receives a Peabody Award.”

Controversy at the New York Public Library

Debate Over New York University’s Expansion

The Future of New York’s Waterfront

Lopate show staff l to r: Executive Producer, Melissa Eagan; Associate Producer, L. Blakeney Schick; Assistant Producer, Steven Valentino; Assistant Producer, Julia Corcoran; and Host, Leonard Lopate at the Podium. (Photo by and courtesy of Daniel Eagan)

2012: WNYC Radio, Public Radio International

Studio 360 – Inside the National Recording Registry

“Each year, the Library of Congress chooses 25 recordings to be preserved as part of its National Recording Registry, ranging from obscure cult albums (Love’s psychedelic pop opus Forever Changes) to inescapable musical gems (Vince Guaraldi’s soundtrack to A Charlie Brown Christmas) to seminal historical artifacts (Eduoard Léon-Scott’s phonautograms from the 1850s). Aired nationally on Studio 360, Inside the National Recording Registry is a series of short documentaries that celebrates these historically significant works through interviews with creators, scholars, and notable fans. Hearing songwriter Giorgio Moroder break down the electronic musical roots of Donna Summer’s” 1 Feel Love” or actor Hugh Laurie rhapsodize about the mysterious lyrics of Professor Longhair’s “Tipitina” gives the listener a sense both of what inspired these recordings and what it’s like to be inspired by them. Producer Ben Manilla and his crew create an engaging listening experience that, in each installment, makes a strong case for the importance of the record in question, whether it’s freak folk, college rock, or cowboy music. Inside the National Recording Registry earns a Peabody Award for its commitment to the preservation of American audio culture”

The Winners: Studio 360 Senior Editor, David Krasnow; Studio 360 Host, Kurt Andersen; Producers Ben Manilla, Erik Beith and Devon Strolovitch. (Photo: Studio 360)

2010: WNYC Radio

Radiolab

“As that rare program that probes the nature of human experience, WNYC’s Radiolab would function well enough. But it’s the marriage of topic (each more thought-provoking than the last) and design (amazingly robust soundscapes and perfect pacing) that makes Radiolab a true work of art. Hosts Jad Abrumad and Robert Krulwich address scientific questions in almost impossibly abstract terms, letting guests and their stories fill in the blanks. Through an exploration of a chimpanzee raised in a human household in “Lucy,” Krulwich and Abrumad seek out the essential qualities that separate animal and human (with surprising results), while “Words” questions the function of language in human development, turning its gaze to such wide-ranging sources as Shakespeare and a Nicaraguan school for the deaf. The beauty is all in the telling. True to its name, Radiolab functions experimentally, constantly testing out new ways to unveil its stories through seamlessly edited interviews, classic “theater of the mind” sound effects, and the well-timed banter of its hosts. Each episode is by turns witty and poignant, and, always, completely engrossing. For providing weekly updates on the human condition with an unending yen for philosophical exploration, Radiolab receives a Peabody Award.”

<h4>Radiolab’s “Lucy,” from February 20, 2010</h4>

<h4>Radiolab’s “Words,” from August 9, 2010</h4>

Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich express their disbelief at winning a Peabody Award…at the Peabody Awards.

2007: WNYC Radio

The Brian Lehrer Show

“Talk radio these days is so overwhelmingly polarized — or polarizing — that ‘The Brian Lehrer Show‘ can seem more like an artifact than an anomaly. But it’s very much in the present, reuniting the estranged terms ‘civil’ and ‘discourse’ five mornings a week like no other show on the air. Lehrer makes the most of New York’s enormous, sometimes fractious diversity. He takes on the most nettlesome issues of the day, from immigration to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to cops-and-minorities, and deftly keeps his studio guests and his call-in contributors both on point and respectful. On his show, New Yorkers of vastly different backgrounds and circumstances get to know each other. In 2007, Lehrer and his production team experimented with new features such as ‘Follow-Up Friday,’ in which an issue from earlier in the week was reconsidered, and ‘Democracy’s Living Room,’ a two-day event during which listeners of all political stripes took turns explaining their stances. Another feature, dubbed ‘Crowdsourcing,’ included such practical applications as using listeners’ reports to expose wild disparities in the price of milk, lettuce and beer from neighborhood to neighborhood. For facilitating reasoned conversation about critical issues and opening it up to everyone within earshot, a Peabody Award goes to ‘The Brian Lehrer Show’.”

<h4>”Gentrification and the Black middle class,” April 25, 2007</h4>

<h4>”Baghdad: View from the ground,” May 24, 2007</h4>

<h4>”Democracy’s living room,” July 5, 2007</h4>

<h4>”From Baghdad to New York,” July 6, 2007</h4>

<h4>”Follow-up Friday,” September 7, 2007</h4>

<h4>”Are you being gouged? The results,” October 11, 2007</h4>

<h4>”The middle ground on the Middle East,” November 28, 2007</h4>

<h4>”Out of Africa,” December 12, 2007</h4>

Executive producers: Brian Lehrer (Host), Nuala McGovern, Chris Bannon (Program Director). Producers: Jim Colgan, Lisa Allison, Priya George, Kate Hinds. Web designer: Amy Pearl.

Left to right: Lisa Allison, Ilya Maritz, Jim Colgan and Kate Hinds, Brian Lehrer, Debbie Fountain, Amy Pearl, Priya George, Chris Bannon, Nuala McGovern and Jody Avrigan.

2005: WNYC Radio

Radio Rookies

“Radio Rookies is ingenious. In the short term, the six-year-old WNYC project generates illuminating feature article/essays by, for, and about teenagers, a radio audience rarely catered to by anyone but music programmers and advertisers. Long term, it may produce a multicultural new generation of audio journalists. New York City teens trained in WNYC workshops take home tape recorders and microphones with which to record interviews with family and friends, ambient sound, and their own ideas and thoughts. With guidance from executive producer Czerina Patel, associate producer Miguel Macias, consultant editor Karen Michel, and mix engineer Wayne Shulmister, they assemble highly personal, 12-15 minute reports characterized by startling candor. The 2005 broadcasts included 16-year-old Catalina Puente’s tale of her obsession with a female classmate she nicknamed “K-licious.” Her account includes her coming out as bisexual to her parents, whose reactions she records as well. Sierra Leone-born Veralyn Williams, 19, reports on her illegal-immigrant status and frustrating quest for a green card, which initially angers her nervous, secretive parents but ultimately prompts them to take action themselves. Derrick Hewitt, 14, captures an instance of his own bad temper on tape and ends up reporting about his feelings of alienation and anger and how he deals with them. For teaching teens the fundamentals of radio reporting and giving listeners unvarnished insights into worlds ignored and disregarded, Radio Rookies is awarded a Peabody.”

<h4>Radio Rookies’ “Moshulu series” from 2005</h4>

Rookies Carlos “Chico” Gonzalez, Veralyn Williams, Derrick “Honeybun” Hewitt and Catalina “Cat” Puente

2004: WNYC Radio, National Public Radio

On The Media

“For one hour each Saturday, On the Media hosts Bob Garfield and Brooke Gladstone take listeners of 185 National Public Radio stations on an insightful journey into the inner workings and outer effects of the media. In a world where a handful of corporations own all of the major media outlets and the need for media literacy is ever increasing, this show provides candid and straightforward examinations of those whose job is to provide the facts of the day. On the Media deconstructs the often black and white presentation of “the way things are,” holding standard media practices up to penetrating critique. On the Media examines these presentations outside their self-generated boxes. Significantly, On the Media also takes on the challenge of addressing international media coverage, offering new perspectives on various topics. The show is comprised of interviews, reported pieces, commentary, and occasionally satire, all marked by vivid language and sound. Gladstone and Garfield rely on the assistance of executive producer Dean Cappello, producers Tony Field, Janeen Price, Arun Rath, Katya Rogers, and Megan Ryan, and web designer Amy Pearl. For filling an important and much neglected need in broadcasting, On the Media receives a Peabody Award.”

<h4>OTM’s <i>The Good Soldier</i>, May 21, 2004</h4>

<h4>OTM’s November 19, 2004 broadcast</h4>

OTM’s Megan Ryan, Dylan Keefe, Katya Rogers, Arun Rath, Bob Garfield, Dean Cappello and Brooke Gladstone.

2004: WNYC Radio, Public Radio International

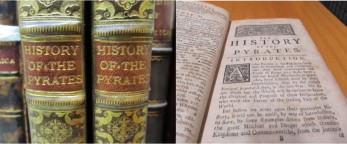

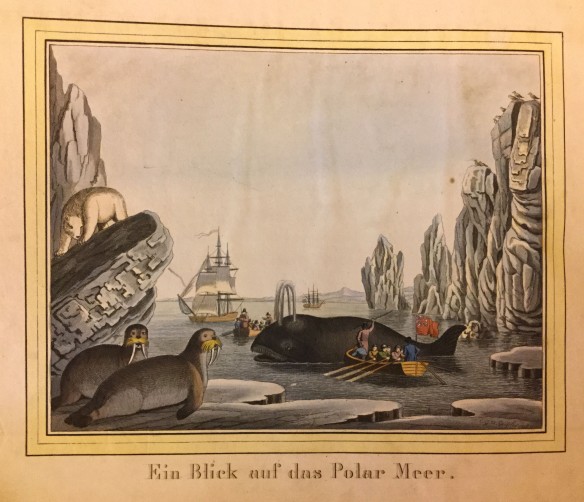

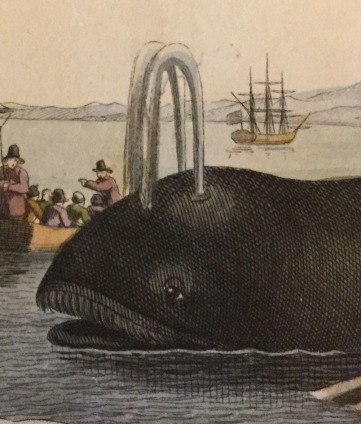

Studio 360 – American Icons – Moby Dick

“In an effort to reexamine what it means to be American, Studio 360 launched a constructive series aimed at understanding American cultural benchmarks, American Icons. This debut installment guides us through Herman Melville’s classic tale of compulsion, rage, and rapture, Moby-Dick. Host Kurt Andersen employs Studio 360’s distinctive format to contextualize the work through modern artists including performance artist Laurie Anderson; playwright Tony Kushner; sculptor and painter Frank Stella; jazz scholar Stanley Crouch; science fiction writer Ray Bradbury; and playwright David Ives, who summarized the mammoth novel in the two-minute world premiere radio play, Moby Dude. Listeners are further brought into the account by actor Edward Herrmann, who gives a visceral performance as the voice of Ishmael. Scholars Samuel Otter and Andrew Delbanco reflect on how the image of Ahab’s maddened pursuit of the whale was widely mentioned in the press after September 11th – as a metaphor for both the attack and retaliation. [The show was] produced by WNYC radio for Public Radio International with executive producer/writer Julie Burstein; director Kerri Hillman; writer Peter Clowney; consulting producer Mary Beth Kirchner; technical director Leital Molad; and writer Edward Lifson. For illuminating and revitalizing a masterpiece with energy, humor, imagination, and verve, and for making “great radio,” the Peabody Board honors Studio 360 American Icons: Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.”

<h4><i>Studio 360’s</i> Moby Dick from November 5, 2005</h4>

Studio 360’s David Krasnow, Michele Siegel, Kerrie Hillman, Arun Rath (OTM), Ave Carrillo, Leital Molad, Julie Burstein, Dean Cappello, and PRI’s Melinda Ward.

Studio 360 Host Kurt Andersen and Executive Producer Julie Burstein

1984: WNYC Radio

Small Things Considered

“In recent years radio programmers have tended to overlook a very important part of the listening audience: children. WNYC Radio is a notable exception. “Small Things Considered” is a live three-hour daily radio program designed especially for children ages 6 to 12. The program successfully combines contemporary, classical and children`s music with bright, informative and creative educational segments. There is also telephone dialogue between the hosts, Kathy O`Connell and Larry J. Orfaly, and children who live in the station`s listening area. For catering to an oft forgotten audience with a program that is both entertaining and educational and for regarding children as an important and worthy audience for radio, a Peabody Award to WNYC Radio for ‘Small Things Considered.'”

<h4>A 1984 broadcast of Small Things Considered</h4>

<h4>A 1984 broadcast of Small Things Considered</h4>

<h4>A 1984 broadcast of Small Things Considered</h4>

<h4>A 1984 broadcast of Small Things Considered</h4>

<h4>1984 selections from Small Things Considered</h4>

Dean J. Thomas Russell and President Fred C. Davison of The University of Georgia present the Peabody Award to WNYC Director Mary Perot Nichols. (Photo: Linda Naklicki, WNYC Archive Collections)

Children’s programming has been a regular aspect of WNYC’s programming for decades. In the station’s Peabody application Program Director Larry Orfaly and Producer Keith Talbot wrote that Small Things Considered “has created a new ‘prime-time’ for children with its carefully balanced product of ambitious adult planning and spontaneous contributions from children. The live production and program’s daily presence; the appealing music; the innovative educational features; and the caring, likable, dedicated hosts have resulted in overwhelming responses.”

WNYC Program Guide, June, 1985

1962: WQXR Radio

“Consistently excellent in its news coverage at all times, WQXR, New York City, merits special praise for lighting a candle in the darkness every night during the New York newspaper strike with its concise, authoritative digest of the day’s news. And in recognition, a Peabody Award for radio news.”

1961: WNYC Radio and The New York Public Library

Teenage Book Talk and The Reader’s Almanac

“It is the considered opinion of the Peabody Awards Board that television and radio, far from being the ogres book publishers once labeled them, are actually a stimulant to the cause of good book reading in America. Proof of the pudding is the resounding success scored by two radio programs devoted entirely to books by station WNYC, New York’s fine municipal broadcasting system. One of the programs is “The Reader’s Almanac,” conducted since 1938 by Professor Warren Bower of the New York University Writing Center [and later by Walter James Miller]. The other is “Teenage Book Talk,” presented, unrehearsed, every Saturday morning by New York Public Library and produced by Lillian Okun. To station WNYC and these two programs goes a richly deserved Peabody Award, with a special vote of appreciation from the Chairman of the Peabody Board.”

<h4>A Teenage Book Talk broadcast from 1961</h4>

<h4>Interview with Marianne Moore, Reader’s Almanac, December 14, 1961</h4>

WNYC’s Director Seymour N. Siegel accepting the awards at the Peabody ceremony on April 10, 1962.

1960: WQXR Radio

“During 1960, the line, ‘For 25 Years, America’s Number One Good Music Station,’ was more than a slogan for WQXR. Its Musical Spectaculars and its total programming of music were indeed of a high order. In recognition, this station has again been chosen for a Peabody Award for radio entertainment.”

1960: WNYC Radio

Personal Award for Children`s Programs

“Ireene Wicker brings to her weekly program, “The Singing Lady,” literate taste, tender understanding, wit, gaiety, and style. A benign sorceress as well as an artist of consummate skill, Miss Wicker has been a steadfast foe of violence and brutality and a true friend to children everywhere. In recognition, [she receives] the Peabody Award for radio children’s programs.”

<h4>A Singing Lady broadcast from 1960</h4>

Ireene Wicker accepts the Peabody Award on May 25, 1961 with WNYC Director Seymour N. Siegel at far left. (WNYC Archive Collections)

(Audio of acceptance below courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection)

<h4>Ireene Wicker accepts the 1961 Peabody Award</h4>

1956: WNYC Radio

Books in Profile

“In “Books In Profile,” which is broadcast by WNYC, New York City, Miss Virgilia Peterson, the well-known critic, author, and lecturer, provides a stimulating insight into the world of books and the persons who write them. This she does with book reviews, interviews with prominent literary personalities, and news items from publishing circles. Her program has charm, perspicacity, authority, and listener interest. In recognition of this important contribution to one of the oldest and most important of the media of communications, books, by one of the newest, radio, the George Foster Peabody Radio Award for education for 1956 goes to “Books In Profile,” WNYC, and Miss Virgilia Peterson.”

<h4>Books in Profile, December 27, 1956</h4>

1956 WNYC Radio

Little Orchestra Society Concerts

“With all the horrible noises, erroneously labeled music, that pollute the airwaves these days, it is a particular pleasure to salute an organization like The Little Orchestra, and its distinguished young conductor, Thomas Scherman. They are providing really beautiful music for a new generation that needs it desperately. For seven years, The Little Orchestra has broadcast six children’s concerts a season over WNYC. The same programs are now picked up by the National Association of Educational Broadcasters, and used with gratifying results by over 100 non-commercial college radio stations all over the country. Long may Mr. Scherman’s baton wave! And here is the George Foster Peabody Radio Award for the outstanding youth and children’s program for 1956.”

<h4>Little Orchestra Society Concert, December 22, 1956</h4>

1951: WQXR Radio

“The New York Times Youth Forum has featured unrehearsed discussion by students selected from private, public and parochial schools, on topics ranging from the political, educational and scientific to the international and the United Nations. These have been broadcast not only locally, but before distinguished audiences in major American cities, coast to coast and over trans-Atlantic facilities. In recognition of the quality and importance of this series, the George Foster Peabody Award for radio youth programs is hereby awarded to WQXR of The New York Times with a special word of recognition to Dorothy Gordon, Moderator, and Mrs. Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger, Director of Special Activities for the Times.”

1950: WNYC Radio

Institutional Award for Contribution to International Understanding for United Nations Coverage

Honorable Mention

“A citation for the promotion of international understanding to station WNYC of the City of New York, for its public service in bringing the official daily proceedings of the United Nations to those in the metropolitan area, and for its consistent UN news coverage and frequent presentation of feature material about the United Nations, in their struggle to bring about lasting peace.”

<h4>A 1950 UN broadcast</h4>

“WNYC’s gavel-to-gavel coverage of the United Nations was more extensive than any other station in the United States at the time. In WNYC’s original application to the Peabody Committee, Program Director Bernard Buck wrote that the station had devoted “an imposing portion of its broadcast time to the United Nations….OVER 1500 HOURS in the past year,” adding that these broadcasts “gave us exclusive coverage of the historic ‘Korean Sunday’ meeting called…just as the news of the invasion reached Secretariat headquarters to meet the exigencies of the South Korean invasion.”

1949: WQXR Radio

“Radio generally has done much to increase and uplift musical appreciation in this country. But no station anywhere has devoted more time or more intelligent presentation to good music than has WQXR. All types of the best in music—instrumental, chamber, solo, opera, and symphonic—have been brought to half a million families in New York alone, plus homes in 14 other states and Canada. And the performing artists have been a veritable Who’s Who in world music. Prominent in 1949 offerings was the Our Musical Heritage Series. In recognition not merely of this and other programs, but primarily to single out and honor the station for its over-all contribution to musical appreciation and good music, the George Foster Peabody Radio Award for outstanding entertainment in music goes to WQXR of New York.”

1944: WNYC Radio and Mayor La Guardia

Institutional Award for Outstanding Public Service by a Local Station

“The Award for the outstanding public service for a local station is to be a double award. The first goes to Station WNYC for having caught the attention and the conscience of our greatest community, and to Mayor La Guardia for his courage and common sense in telling us what is wrong.”

<h4>Mayor La Guardia on November 26, 1944</h4>

WNYC’s first Peabody Award. (Photo courtesy of the La Guardia Photo Collection, La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College, CUNY )

This was WNYC’s first Peabody Award. In WNYC’s original application, Station Director Morris S. Novik wrote that the Mayor’s WNYC broadcast covered “a multitude of problems and exigencies that arise in a tremendous city like New York. He is constantly seeking to improve the welfare of the community and feels that the most direct contact with the people he serves is through the medium of radio.” Novik added that the broadcast reached “an audience unequaled by any other program on the air at that hour,” noting that the Pulse of New York survey gave his broadcast a rating more than three times that of its closest competitor. (Pulse was a source for measuring local radio audiences at the time)

At the award ceremony in the Commodore Hotel, City Council Newbold Morris gave a stirring tribute to the station. Morris Novik also spoke:

Newbold Morris and Morris Novik speak at the 1945 Peabody Awards Ceremony

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

WNYC’s first Peabody Award shared with Mayor F.H. La Guardia.

(La Guardia Artifact Collection, La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College, CUNY)

Peabody award given to Mayor La guardia and WNYC Director Morris S. Novik by John E. Dewey, April 5, 1945.

(The La Guardia & Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College/The City University of New York)

1940: WQXR Radio

Honorable Mention

Institutional Award: WQXR Radio for High Standards of Musical Progress

(no citations written for 1940)