In college student life, it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference between raucous traditions and random acts of stupidity. Traditions often degrade over time, ultimately ending with some egregious incident — or series of them, each progressively worse — that causes their dissolution . At Amherst College, the statue of the mythical nymph Sabrina is perhaps the best known but not the only example. Fraternity hazing rituals, silly pranks, drunken stunts, rivalry-fueled acts of humiliation, stolen vehicles, property damage — these, unfortunately, are constants at colleges and universities. But the nature of such incidents, and the nature of college traditions in general, have a somewhat different flavor in earlier eras as compared to today; it may be the long winters, the lack of entertainment options, the stifling isolation of campus life, and the inherently strict moral codes of its community that have made colleges a breeding ground for antics of every sort. Many of them are documented in the College Archives, though probably the great majority of them are not.

. At Amherst College, the statue of the mythical nymph Sabrina is perhaps the best known but not the only example. Fraternity hazing rituals, silly pranks, drunken stunts, rivalry-fueled acts of humiliation, stolen vehicles, property damage — these, unfortunately, are constants at colleges and universities. But the nature of such incidents, and the nature of college traditions in general, have a somewhat different flavor in earlier eras as compared to today; it may be the long winters, the lack of entertainment options, the stifling isolation of campus life, and the inherently strict moral codes of its community that have made colleges a breeding ground for antics of every sort. Many of them are documented in the College Archives, though probably the great majority of them are not.

Last year I wrote about the “Squirt-Gun Riot of 1858,” which seems to have put me on the lookout for more “Acts of Stupidity” (yes, that’s an actual subject heading in our General Files, where we compile odds and ends related to the history of the college). Today let me share a few more of these with you. (Maybe this will be an occasional series?)

1. Chicken Stealing: William Hubbard (AC 1844), Non-Graduate

Hubbard’s problem seems simply to have been impulse control. He was dismissed from Amherst for a string of offenses culminating in the incident of March 5, 1842, involving the theft of chickens. Hubbard later graduated from Brown University (1845), practiced law in Minnesota, and later taught school in the South. Interestingly, despite his unfortunate experience at Amherst, he sent three of his sons there (William 1871, Charles 1876, and Edward 1885).

This letter from Prof. William S. Tyler (PDF) lays out the facts:

Amherst College, Mar. 9, 1842.

Mrs. Hubbard

Dear Madam,

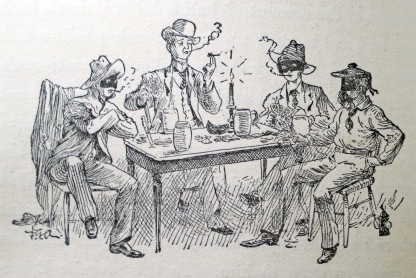

I regret extremely, that I am obliged so soon again to be the bearer of unwelcome intelligence respecting your son. When he returned, he made many fair promises of amendment both as a scholar & a Christian. But he has disappointed our hopes, returned to his former bad habits & even committed higher misdemeanors. You will learn, what I mean, from the following note of the Faculty: “Whereas on Saturday night the 5th of March last, Sophomore Hubbard, after indulging in festivities & cardplaying till a very late hour with several of his classmates at the room of a classmate, proceeded with one of his companions to take without liberty several fowls from a neighboring barn roost for the purposes of continuing the entertainment, & whereas this is but one of a series of offences of which he has been found guilty & for which he has been subject to college censure; therefore vote that he be & hereby is dismissed & that his parent be informed, that unless there is a radical change in his character, it cannot be safe or [wise?] for him ever to return to this college.”

I feel constrained to add, not for the sake of distressing you more, but for the purpose of acquainting you fully with the facts, painful as they are, that besides cardplaying & Sabbath breaking (for by our laws, the previous night is regarded as a part of the Sabbath) the misconduct of your son was aggravated by falsehood & misrepresentation.

I think, Madam, you will agree with the Faculty that unless there is a radical change in his character, there will be as little [encouragement?] for you to send him back to College, as for us to receive him. Dismission necessarily involves separation from College for one year. At the end of that time, should you wish to send him to another College, we shall interpose no obstacle. That you may be sustained & sanctified under this event so painful to us as well as to you, is the sincere desire of myself & all my associates in whose behalf I write.

Yours Truly

Wm. S. Tyler

2. The Burning of the Peagreen Beanies (I) – 1927

As I wrote in an earlier blog post, several generations of Amherst freshmen in the first half of the 20th century were forced to wear these universally loathed, completely fashion-backward wool beanies (above) when out in public during the first months of college. Ostensibly their purpose was to identify members of the incoming class, but their true purpose, of course, was a not very subtle form of ritual humiliation: the Sophomore class asserting its newfound superiority over another peer group. Because they had to endure it, now it was time for the class below them to endure it too.

Amherst Student, Feb. 24, 1927

In late February 1927, when the members of the Freshmen of the Class of 1930 were no longer required to wear the hated beanies, they celebrated with a ritual ceremony of burning them in a bonfire. This had apparently become a tradition for the past few years. As this report from the Amherst Student (right) entertainingly describes, the celebration got a bit out of hand, with the freshmen taking over the streets of downtown Amherst, blocking trolleys, snowballing the police, turning around passing cars, and generally acting like prisoners released from confinement. The ugliest business occurred with the “liberation” of a trolley conductor’s cap by an unnamed assailant.

The archives has the following letter from the president of the Freshman class apologizing to the president of the trolley company, and the latter’s surprisingly good-humored reply:

(The cap-stealing part of the incident will no doubt remind P.G.Wodehouse fans of the hilarious efforts of several characters in his stories to steal policemen’s helmets on Boat Race Night at Oxford and Cambridge. Is it possible that the Amherst miscreant had Wodehouse in mind? Please enjoy this video homage.)

3. The Burning of the Peagreen Beanies (II) – 1930

The last incident I’d like to present also involves the cap-burning ritual, this time three years later. However, this had a much more serious and tragic outcome, and brought a lot of unwelcome sensational press coverage to the college.

During the week leading up to the February 22, 1930 cap-burning, freshmen had kidnapped some of the sophomore officers, so several members of both classes were ready for a battle. Freshmen arranged a large pile of wood on the lawn in front of Converse Library; if they successfully guarded the pile until 6 p.m., then by agreement they could have their fire in peace and burn their caps. If the Sophomores burned the wood before that time, or in some way prevented the fire, the Freshmen would have to wear their caps for a few more weeks.

During the week leading up to the February 22, 1930 cap-burning, freshmen had kidnapped some of the sophomore officers, so several members of both classes were ready for a battle. Freshmen arranged a large pile of wood on the lawn in front of Converse Library; if they successfully guarded the pile until 6 p.m., then by agreement they could have their fire in peace and burn their caps. If the Sophomores burned the wood before that time, or in some way prevented the fire, the Freshmen would have to wear their caps for a few more weeks.

The Sophomores gathered on the hill near the Octagon about 5 p.m. Suddenly they rushed down the hill with buckets of what appeared to be water, which they attempted to throw on the wood. They succeeded in getting themselves and the Freshmen as well as the wood thoroughly soaked. They returned to the Octagon, and then again very suddenly rushed down with blow torches. As Richard H. Plock (AC 1930) relates in a letter,

We discovered to our horror that they had gasoline in the buckets. In no time at all there was great confusion. Some of the boys tripped with the torches, others aimed them poorly, and before we knew it, the clothing of several of the sophomores and freshmen was on fire. […] Several of the boys received rather bad burns, but fortunately none were fatally burned.*

The Dean wanted to issue a harsh punishment to the entire Sophomore class, but officers of Scarab (an honor society then active at Amherst at that time which was mainly responsible for overseeing college traditions) intervened and had penalties loosened somewhat. However, this marked the end of the cap-burning tradition forever.

—

* TLS to Walter B. Mahony (AC 1936), Apr 23, 1936, in General Files: Student Life and Customs: Cap Burning.

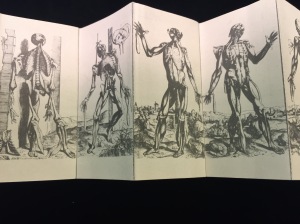

This isn’t really one of the ghost stories in the Christmas Greetings Collection. Instead, these skeletons are the “Vesalian muscle-men,” a series of anatomical drawings from one of the earliest and most important works on human anatomy, Andreas Vesalius’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543). The book in the Christmas Greetings Collection was published in 1944 by Henry Schuman, an antiquarian bookseller who specialized in the history of medicine. It makes sense that he would send anatomical drawings to his friends at Christmas.

This isn’t really one of the ghost stories in the Christmas Greetings Collection. Instead, these skeletons are the “Vesalian muscle-men,” a series of anatomical drawings from one of the earliest and most important works on human anatomy, Andreas Vesalius’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543). The book in the Christmas Greetings Collection was published in 1944 by Henry Schuman, an antiquarian bookseller who specialized in the history of medicine. It makes sense that he would send anatomical drawings to his friends at Christmas.