On April 24 Armenians commemorate the genocide of 1915. The event is marked every year, but the centenary in 2015 has particular resonance and will be widely noted.

Even so, what happened in 1915 and the years that followed was not the first time of troubles for Armenians in Turkey. The nineteenth century had seen many massacres and had ended with several years of intense conflict now known as the “Hamidian Massacres” (named for Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the troops, mostly Kurdish, he used against the Armenians).

Since several Amherst College missionaries were in the region for decades, the Archives and Special Collections contains many eyewitness accounts of what happened during the last years of the century. Most of the missionary accounts are in fairly obvious places, in what we think of as “missionary collections.” But there was one folder in another collection that lay quietly for many years, a folder in the Harrison Griswold Dwight Papers.

Since several Amherst College missionaries were in the region for decades, the Archives and Special Collections contains many eyewitness accounts of what happened during the last years of the century. Most of the missionary accounts are in fairly obvious places, in what we think of as “missionary collections.” But there was one folder in another collection that lay quietly for many years, a folder in the Harrison Griswold Dwight Papers.

Harry Dwight (1875-1959; AC 1898) was born in Turkey to a family of missionaries but was not a missionary himself. His life was a more literary one, and his papers are filled with interesting correspondence and other writings from his career. Sometime in 1941 Harry wrote his cousin Mary W. Riggs (1873-1943) to ask for a packet of letters that had belonged to his father, Henry Otis Dwight (1843-1917), an important missionary based in Constantinople who married two of the Bliss sisters, thus linking him with our Bliss-Ward family of missionaries.

Mary sent the letters to Harry Dwight with a letter saying essentially, here, take them, I can’t stand to be reminded of what happened in those awful days. Her letter was short, typed, and persuasive, but most of the letters she sent Harry were in cursive, and in faded ink at that. So for several reasons (location of letters in an unexpected collection, difficult handwriting, insufficient description), and despite Mary’s urgency, the letters seem to have remained unread and untranscribed.

Mary sent the letters to Harry Dwight with a letter saying essentially, here, take them, I can’t stand to be reminded of what happened in those awful days. Her letter was short, typed, and persuasive, but most of the letters she sent Harry were in cursive, and in faded ink at that. So for several reasons (location of letters in an unexpected collection, difficult handwriting, insufficient description), and despite Mary’s urgency, the letters seem to have remained unread and untranscribed.

Given the centenary of the Armenian Genocide, it seemed that the letters might prove of interest or use to people interested in Armenian and Turkish history, and it would remind us too that the Armenians were being massacred in the region well before 1915. What follows below are excerpts (long enough as it is) from the transcriptions, with pdfs to the full transcriptions and a separate pdf of the originals for anyone who wants to read the letters in full and see what the manuscripts look like. A little of the punctuation has been changed, and it would be hard to claim complete accuracy in some of the names of places and people, but the transcriptions in the pdfs are otherwise unaltered and unabridged.

Henry Otis Dwight, ca. 1880

It’s important to note a few things about Henry Otis Dwight, who either wrote or received the letters. Turkey was home to him – he knew how to “gad about” (as he says) and how to obtain and report information. As the letters show, he was a serious man and, I think, someone who always had in mind “the big picture.” In Dwight’s case, the big picture involved protecting his “flock” (the Armenians) and the missionaries stationed precariously across a vast empire, and he feared for the safety of both groups during conflicts. In all that transpired during the years the letters cover, Dwight’s view of the situation – and the criticisms he offered – were directly connected with the impact on his larger mission. He was evenhanded: if the reader feels insulted on one occasion, he will be soothed on another. Dwight had harsh words for Turks, Kurds, and Armenians (as well as the reporter for the New York Herald), and he was self-critical too, but he was also very willing to praise when praise was due. Although he knew high-ranking leaders on all sides, he doesn’t come across as especially political, except to use the tools of politics to help his cause when he could (and often he couldn’t). He was both eyewitness and gatherer of information from other eyewitnesses, and in these letters he reveals all he knows.

*****************

The Bliss Bible House in Constantinople, H.O.Dwight’s base of operations

Letter of September 30, 1895:

HOD-1895-Sep-30

I went over to Pera about 11, and in coming back could see that something was astir of an unusual nature. The police swarmed in the streets and on the bridge and eyed me in a very embarrassing manner. Just then a fire broke out in Beshik-tach, and it was impossible to tell whether the excitement of the people was on account of the fire or not. While I was on the bridge the Grand Vezir, Said Pasha, came along on his way to the Porte. He had evidently waited at his house until the demonstration should have time to be broken up. Aside from the multitude of police and the unusual crowd at the head of the bridge, I could not see that any great thing was taking place. After I reached the Bible House, I was told that the demonstration had occurred, and had been attacked at Nouri Osmaniye by the troops, when about twenty Armenians had been sabred by the cavalry. Shortly after, a man came in who said that he had seen two fights between Armenians and the police at the Sublime Porte. The first was at the upper door, where the ministers enter. He saw one man carried off as if dead. Later the second fight occurred at the lower door of the Porte, and there he saw two or three fall. He thought it dangerous to linger in that region and left. After the Grand Vezir reached the Porte the police began to make arrests of Armenians. They seemed to search for arms and to seize those who had anything that could be called a weapon, if only a large pocket-knife. I went out from the Bible House rather late, to go to the steamer, and saw nothing but a rather anxious look on the faces of the people. The police were everywhere but I saw no arrests made although I went the longest way to the bridge in order to observe the signs of the atmosphere. The Turks were whispering together and the Armenians were conspicuous by their absence. Many stories were afloat about the result of the fights. The Armenians are said to have killed a Turkish major who fired upon them. Tuesday, Oct. 1. The Turks at the steamer landing at Hissar were very much occupied with secret whispering, and I thought eyed me askance as I went to the steamer. There was nothing in the paper about the affair of yesterday except a bland sort of declaration that the Armenian hamals and firemen had gathered together at two or three places in the city and had been dispersed by the police, and that under the shadow of the sultan quiet was perfect in the city. There were no Armenians on the steamer and the Armenian shops in the city were mostly shut. A general hush ruled the streets. Everyone spoke in low tones and the coffee houses were deserted. The impression was of a sultry day absolutely still before a thunderstorm. I encountered a number of Softas on the streets who looked very savage and who I observed had revolvers under their long gowns. Altogether the impression of my morning jaunt in the city was not reassuring. It was evident that the Turks are angered by the affair of yesterday and are on the lookout for more trouble, or to make it. The police are patrolling the streets but only by twos, except once in a long while a mounted patrol passes of more men.

Scutari neighborhood of the Dwight and Bliss families (image from the Mark Hopkins Ward Papers).

…A number of our Bible House people came to me, thinking that I could do something, to beg that I would get protection for them. They were in utter terror of their lives. They say that the Softas are going to make a general massacre, and that at the same time that the police are arresting every Armenian who has anything like a weapon they are allowing the Turkish mob to buy revolvers unmolested. I found from other sources that this was true as to the purchase of revolvers. Then came word that two of the Bible House men, one a printer and the other a hamal, had been arrested and very badly beaten. Help was wanted to secure their release, for it is rumored that they are killing the prisoners in cold blood at the Ministry of Police. A few minutes later word came that Garabed Senakirinian, one of the leading Protestants of Gedik Pasha, was arrested last night and no one knows whether he is alive or dead. He was at the new Gedik Pasha chapel when some Softas came in and ordered the people to stop working in the chapel. “We are not going to allow you to have a chapel here,” they said. Garabed Eeffendi went out and spoke to the women of the congregation who have been doing watchman’s duty there while the men were at work, telling them to go inside because the Softas looked so fierce. The Softas at once went and complained to the police that he had told the women to stone them, which was false, and the police arrested him. Happily, a Turk standing by had seen the whole performance and told the police that the Softas had lied and got him released. Shortly afterward on some threat from the Softas, the police rearrested him and sent him to prison.

All these things come to me, and everyone looks to me to right all wrongs, as if I were their father or their advocate with the powers that be. They were very bitterly disappointed when I told them that I should not go to the British Embassy to present their case because it is already known, and that I did not believe that the British fleet would necessarily be summoned at once to restore order. The feeling that the appeals of these people produces is one of terrible anxiety, for the stories are heart-rending and the possibility that I might with a clearer inspiration find some way to help them is very wearing upon the nerves. It is very much as if we were in the midst of a military campaign and oppressed with the weight that belongs to the period just before the battle begins, when no one knows just what he will have to do in the next minute. It is a little curious that I have not been disturbed by a sense of fear for ourselves.

Several of H.O. Dwight’s family members were with him in Constantinople well into the mid-1890s: Isabella Bliss, widow of Edwin Elisha Bliss (AC 1837) with granddaughters Isabel and Helen, ca. 1895.

…Last evening a man came to the Bible House in great terror, from Donjian’s shop, to say that the police had just made a raid upon the shop as a place where arms are being sold to the Armenians. Donjian is a jeweler and curio merchant, a leading member of the Y.M.C.A. and son in law to Pastor Avedis Constantian. All the antique weapons were gathered up by the police as evidence of treason and carried off with Donjian himself to the Minstry of Police. What to do for this poor fellow was the problem and we could do nothing. We concluded that at the Ministry of Police there would be someone wise enough to see that swords from the time of the Crusades and flint-lock pistols of two or three centuries ago are not arms in the sense of the law. This morning I found that he had been released and went around to his shop on my way to the Bible House to congratulate him on his escape. He was badly frightened and nervous but thankful to get off with the loss of his goods, which had been kept by the police, to the value of £20.

…Later in the day I went over to Gedik Pasha, ostensibly to call on Mrs. Newell on the occasion of her arrival from America, but really to get a clear idea of the general situation and of theirs in particular. Just before I left the Bible House, there was a rather sharp shock of an earthquake. As soon as Mrs. Newell saw me she said, “It takes an earthquake to bring you here.” I then remembered that since the earthquakes of July 1894, when I went over to see how the ladies had passed the danger, I had been only once in their house. The three ladies were in good spirits and full of pluck. They had not seen any disposition to attack their house and felt that there would be no such attack. They had seen the Softas roaming in parties of ten or more through their street, armed with revolvers, daggers, and clubs of a uniform pattern. They had heard the horrid sound of the blows of the clubs striking on the heads of the victims in the street, which they said sounded like pistol shots, and they had comforted and helped the poor women left alone in their houses by the arrest of their men. But no harm had come near them and they were not inclined to wish any help.

…. Numbers of Armenians have asked us when the fleet will be here, and I have been obliged to tell them that I am inclined to think that the rising of the Hunchagists [Armenian revolutionaries] has made its coming now impossible unless the government ceases to show the purpose to protect the people generally from the mob. The appeals of these people for advice, the terrible nature of their position, and the utter uselessness of their hoping help from me, make a combination of influences that crush me under the sense of responsibility and impotence. I feel like crying aloud, “Oh, Lord, my burden is greater than I can bear.”

Letter of October 7, 1895:

HOD-1895-Oct-7

Thursday, Oct. 10. The other day Dr. Matteosian asked me what I would advise him to do about his family who are in Biryukdere. Should they stay where they are, or should they return to their Pera home? I told him that for the moment Pera is less safe than the Bosphorus because of the tendency of the Armenians at the church of the Holy Trinity to make trouble. I told him the only way was to do as I do every day – feel the pulse of the city and so judge of dangers. He said the difficulty was to get hold of the pulse. This morning he met me on the steamer and asked me how the pulse is this morning. I told him it was less violent, but that I had not yet been to the city to find out. Just then I met Mr. Dimitrof, the Bulgarian agent here, and asked him about the situation. Dr. Matteosian listened with all his ears and understood something of how I work to get the situation every day.

Certain men I know to be well informed and to be willing to tell me what they know. One of these is Mr. Dimitroff; another is the agent of the Reuter News Agency, who gives me news and I give him items that he cannot otherwise get. Then I go among the people of all classes and hear what they have to say; their experience with the police, and with the common Turks or Armenians, and their preposterous ideas on all subjects. From this it is easy to get a general notion of how the mind of the city is acting and if there is anything that seems to have special danger in it. I take pains to learn if it is known at the Embassies. What Mr. Dimitroff told me was that yesterday afternoon Said Pasha, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, called on the Austrian Ambassador, who is Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, and asked him to get the ambassador to negotiate with the Armenians about leaving the churches and going to their homes, authorizing the Ambassador to promise that none of them should be arrested by the Turks if they leave the churches. This involves a tacit admission by the Turks that the Armenians have been driven into their present position by abuse, and that therefore they are not to be punished for refusing to submit at the order of the Government. Upon this, the ambassador held a meeting at the French Embassy and decided to undertake the negotiation. This morning early the dragomen of the six Powers were sent to the city to go to the churches and advise the people to go home, promising that they will not be molested by the police. I have not been able to learn what the result has been, but I am afraid that the effort has failed. The Hunchagists are determined to keep up the demonstration until the Turks yield consent to the reformers. Today the Hunchagists went around and informed Armenians who opened their shops that they have been fined by the revolutionary committee for doing so. Several men paid considerable amounts to save their necks from the Hunchagists. All the shopkeepers received orders to close their shops on pain of death from these same revolutionists. They commonly obey meekly for they are terrified at the fear of secret assassination.

Letters from (apparently) Armenians, probably pastors or other employees of the missions:

HOD-1895-Dec-28-29

From Arabkir

December 28, 1895

It was a great comfort that some friends escaped the fatal massacre (Nov. 6) but the five Nalbandian brothers were taken by guile to the government house. They were bound together and shot and many others in the same manner. These have been killed and that is past but many others remain in prison hungry, naked and miserable and they have no means of comfort whatever. Call, oh call for assistance. There are women who were accustomed to dress well and adorn their persons with costly ornaments now naked and miserable hunt[ing] through the ruined buildings to collect the charred wood to sell to cover their nakedness. The churches and schools have become the refuge of many refugees who wander about from morning till evening begging and they return in the evening empty-handed, hungry, weary, cold, and almost dead and they sleep on the stones. Dear friend my eyes fill, my hand refuses to move and how can I write more?

From Keghi

December 29, 1895

I have begun to distribute the £50 which you sent. But the number of the plundered is more than 10,000 of whom 5000 are in the extremest destitution. To whom will I give this £50?

From Erzingan

December 21, 1895

I received your letter with the 15£ draft but it was impossible to cash it and so I return it to you. The only way is to send money by post. As this is the case you better send directly to Kemakh anything you decide to send there.

As to your question: As far as I have been able to find out there are 15,000 persons who are in need of bread and who cry out “bread, bread.” Some have food for a month, some for two weeks. As time passes, the destitute will greatly increase. At present we are in great fear and terror. Oh, we have become wearied with this uncertain life. Every day the fear of death is upon us. We call out, “My God, my God, has though forgotten us?” The pain of this terror is very great. To live upon the earth has become a weariness. What shall the end be? If you have a word of encouragement, write us quickly.

No. 17 [Station report: H.O. Dwight’s summary of information he has received from various stations]:

HOD-1896-Feb-15

Map of The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM).

Constantinople, Feb. 15, 1896

Dear Friends,

Marsovan Station, the Western Mission, and in fact the whole mission force in Turkey is grievously smitten in the death from small pox of Miss King of Marsovan on the 1st of Feb. She was a devoted Christian, skilled to work and win souls, and the Providence which calls her away brings her associates quite as much amazement as it does pain and grief.

Ramazan [Ramadan] gives occasion for some anxiety as to the preservation of the peace. There is real danger of disturbance here also which is too serious to be ignored. But it should be borne in mind by all that the Government is now evidently doing its best to prevent any further misdeeds of the character that we all know to the extent of losing our confidence in the good intentions of those we have trusted hitherto. The Government will not now connive at any outbreaks. At BITLIS the situation is not agreeable. Calumnies against Mr. Knapp have reached a point now that leads Armenians in the villages to believe him the cause of all the troubles which have overwhelmed them. The Porte wishes to try him there on definite charges. He will probably come on here under British protection for conference with Mr. Terrell, who refuses, naturally, to admit any right to try him. At AINTAB (Jan. 30) threats of massacre are continued. The wife of the pastor at Birijik and the two girl school teachers were taken by Gov’t order under escort to Aintab and delivered safely. They saw awful things. Mr. Sanders reached OURFA safely, Miss Shattuck has had Pneumonia but its better. She writes (Jan. 29) that she feels she must stay with the stricken people there, at least [for]] a time. The slaughter at Ourfa was greater than first reported. The Protestants of the Birsjik and Roumkale region have become Muslims along with the others. At Aintab there are about 3500 destitute receiving aid. At MARASH (Jan. 28) there are over 5000 receiving aid and an expectation of 20,000 more as soon as the settlement at Zeitoun question [?] opens up that region to access. At HAJIN (Jan. 29) 1500 people are receiving aid, about half of them from outside the town. SIVAS (Feb. 5) cries for more money, having learned more fully the destitution at Gurun and other places. At CESAREA (Jan. 27) Messrs. Fowle and Wingate have visited ten villages in the Gemerek region where 1000 houses will have eaten up their last grain by the end of this month. About 75 bales of clothing sent from here have reached Cesarea, and the most part have gone on to Sivas and Harpoot. At ERZROUM Mr. Chambers is crushed under the relief work, and Mr. Mac Naughton of Smyrna goes on today to reinforce Erzroum. Dr. Andrus of MARDIN telegraphs of 10,000 destitute in the Kurdish mountains, needing £2000. Mr. Peet has telegraphed promising the money. HARPOOT (Jan. 30) has about 100,000 destitute in 200 places dependent on it. Mr. Gates says he does not get time to eat, but does not mind that, if only he can be sure that he will not be told there is no more money. Up to that date Mr. Peet has received Zt. [zolota] 14,300 for relief from abroad. Besides this, £10,000 has passed through his hands from native sources.

Letter of August 26, 1896:

HOD-1896-Aug-26

An Armenian shop, probably in Harpoot ca. 1910 (image from the W.E.D.Ward Papers)

One of our Armenian neighbors at Roumeli Hissar was in the street back of the custom house in Stamboul when the Kurds were rushing out in pursuit of the fleeing Armenians. He sprang into the shop of a Turk who hid him. Soon after a Jew also took refuge in the shop and the Turk hid him, but the mob hunted him out. The Jew begged for mercy, explaining that he was an innocent Jew, but the ruffians said that Jew or Christian he was a Giaour, and killed him. They did not find the Armenian, who came home to Hissar nearly dead with fright.

…Thursday, Aug. 27.

It is the day for my making up the local news for the Avedaper [an Armenian newspaper] today, and it seemed necessary to go to the Bible House, although I was quite sure that none of the translators or printers would be there. I have had a curious feeling all day exactly like the feeling at the beginning of every battle during the war. It is a profound desire to be somewhere else than in the disagreeable midst of disturbance. I am a coward by nature, I suppose, and am only able to be anything else by the grace of God.

…I went to meet Misses Webb and Montgomery at the train and found that the word had reached the family in spite of my negligence. So they were all there at the station before me and there was a joyful scene when the train came in for the ladies had been told at Philippopolis that 7,000 people had been killed in Cons’ple. All the trouble seems to be over for the moment and we can now count up the losses, first sending a telegram to Boston for the reassurance of our friends. The affair as a whole is the crowning infamy of the infamous reign of Abdul Hamid. For 36 hours the lowest rabble have been allowed to wreak their hate on the Armenians in all parts of the city without hindrance. Of course the folly of the revolutionists was the excuse. But the men who made the outbreak were in general allowed to escape, and the cowardly assassination of near 5,000 unarmed and defenseless people who feared the revolutionists more than the Turks do was a crime which throws into the shade entirely any folly or crime of the anarchist Armenians whom the Turkish troops could have disposed of in an hour without shedding a drop of innocent blood.

…Today I have seen family after family walking the streets weeping, barefoot, bareheaded men, women and children alike dressed only in their night garments with some dressing gown or old shawl thrown over them, these being all that is left to them of their property, and they left to seek some shelter where they can hide their shame of abject poverty and seek a beggar’s crust. The men who did these things were not men but devils. They stripped the houses and in every case destroyed with axes pianos, tables, bookcases, chairs and other property that they could not carry away. They were not content to kill with clubs, they cut to pieces with knives. I have come across more than one large stone with a bloody point that told the story of its use to crush some wretch’s skull. There was no pity, no conscience, no thought of anything but glee in the festival of gratified hate and bloodthirsty passion for gore.

…I have nothing more to say of these horrors. There are no words left in which to describe them. I feel like a sneak for being here, protected by my flag, while these poor wretches have been butchered for looking longingly at the freedom which those have who have flags of their own.

…In town I found all quiet but a terrible fear among all the people. I forgot to say that in the morning a young woman came up to me who declared that she knew the plans of the revolutionists and that a new outbreak was to take place about the middle of the afternoon, which would exceed anything yet seen in violence. She therefore begged to be allowed to move into the college premises. I gave the usual answer, that people may not come merely for fear but that if there is a real massacre commenced in Scutari they will all be received at the college. “Yes,” she said, “after we are all killed you will open the gates for us.”

…I made this journal in three copies in order to send to all the different centres of our family. But just before I went to Scutari Sunday, Mr. Terrell told me that I must destroy any papers which I did not care to have the Turks see, for a search of the houses might be made. So I tore up the two other copies and by mistake tore up clearest one. Please let this go the rounds and reach Grandma and Uncle William and Cousin Charlie as well. Let it be understood that no part of it must be given to the newspapers on any consideration whatever. We are all well and hopeful that the Hand which has been our guard hitherto will still keep us safe. But I am very glad that Isabel and Helen have not had the horrors of these days to go through.

Additional letters and pdf of originals:

HOD-1893-Mar-8

HOD-1893-Mar-16

HOD-1893-Mar-17

HOD-1893-Apr-2

Dwight-HG-BxX-F9-sm

![]()

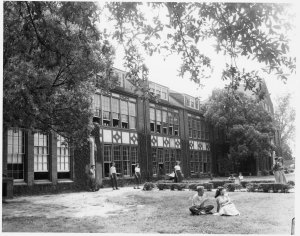

More information on Amherst College’s participation in the national strike of May 1970 can be found in the Moratoria Collection, General Files (Political Activity and Activism), Photographs Collection, and other sources in the Archives and Special Collections.

More information on Amherst College’s participation in the national strike of May 1970 can be found in the Moratoria Collection, General Files (Political Activity and Activism), Photographs Collection, and other sources in the Archives and Special Collections.