Make room in Times Square: the Class of 1852 is ready to party with you and ring in 2015 dressed in spanking new glass.

This group of 42 men has been the subject of two posts, the first about their wild and crazy Philopogonian ways, and the second about a project to reseal the individual daguerreotypes from the class. I recently resealed the last daguerreotype in the group, so we begin 2015 with a sparkling set of nice, clear photographs.

D. J. Sprague: plate showing photographer J.D. Wells’ stamp at bottom right.

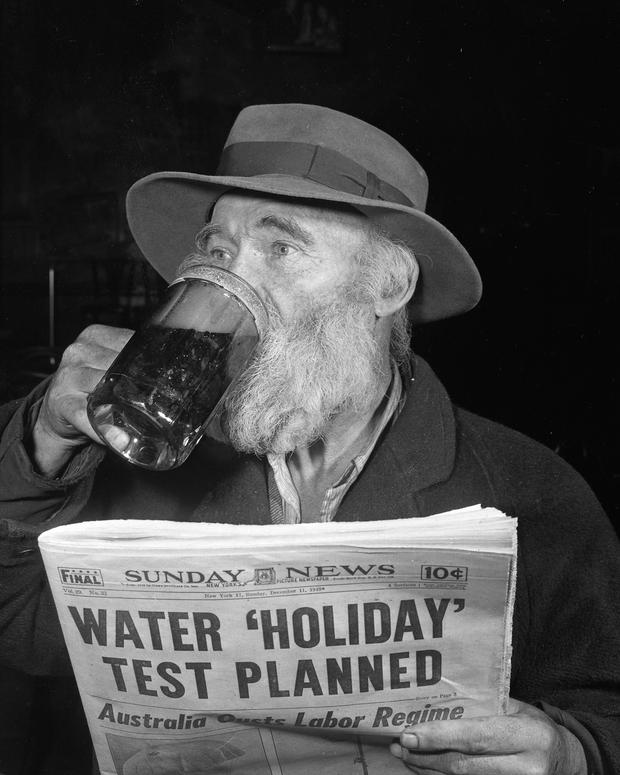

First, a few details about the daguerreotypes themselves: All 42 daguerreotypes are sixth plate size (approx 2.75″ x 3.25″). The plates have a variety of damage but most looked pretty good after merely replacing the old cover glass (with its fascinating variety of gunk) with new Electroverre low iron glass that I cut to size. I do not rinse or otherwise treat the plate except to gently blow off dust. Class member Daniel J. Sprague’s plate had the photographer’s name (J.D. Wells) stamped on the plate itself — an unusual practice — and another plate had Wells’ name on the mat. All others were unmarked but most were also probably by Wells.

Title page of “Pebbles from the Lake Shore,” by Charles Leland Porter

In working with the daguerreotypes, I of course wanted to know more about the subjects and so turned to their biographical files as well as the 1973 Biographical Record (Class_of_1852_record). Of the members of the class, at least 6 served in the Civil War: Almy, who was a quartermaster and whose biographical file says that he designed the regimental flag for the 24th Connecticut Volunteers; Cheavens, who fought on the Confederate side and left a journal of his experiences; Kimberly, a surgeon in the war; Larned, whose wartime career is colorful and well-documented; Littlefield, who served in the war 1861-65; and Porter, who was also a teacher and poet — his book Pebbles from the Lake Shore is in the collection.

8 members (Benjamin, Blair, Dudley, Glenn, Kies, Kingsbury, Roel, and Root) — about fifth of the class — died within a decade, 7 of them by 1856 of (among other things) typhoid, cholera, scrofula, and tuberculosis.

3 members of the class were longtime missionaries, Allen, Barnum, and Bliss. The latter was also the founder of the Syrian Protestant College, now the American University of Beirut. All three men spent decades in the Middle East and chose to retire and be buried there.

Other especially interesting members of the class include William Goodrich, who had a long career in the law; Brainerd Harrington, who was a good friend of the Dickinson family; Henry Root, another friend of the Dickinsons as well as of Helen Fiske (Helen Hunt Jackson), and William Rankin, born in “Little Chucky,” Tennessee, who self-reported to the biographical record that he was “exiled to New York for Union Sentiments.” He had a long, active career, including a period as president of Washington Female College.

Earlier in this post I used the highly technical term “gunk” to describe some of what I found on the old glass covering the daguerreotypes. In the before-and-after pictures below you can see some of the variety of gunk that forms on glass over the course of 162 years, as well as some of what remains on the plate when the glass is removed. In one or two scans I removed some of the brown stains covering the face, but in other cases I left them as is.

Theodore Benjamin, d. 1855. His bio file includes a moving note from his father written after Theodore’s death, as well as the text of Theodore’s graduation speech, in which he says goodbye to Amherst.

William W. Goodrich, lawyer in New York specializing in maritime law.

Henry Kies, licensed to preach but died in 1855 before he had much of a chance at it.

Augustus G. Kimberly, surgeon in the U.S. Army during the Civil War, with a long medical career thereafter.

Sidney K. Smith, teacher and analytical chemist.

Daniel J. Sprague, businessman, publisher, President of Pelham and Port Chester RR.

In my previous post about the class (linked above), I included a scan of the group daguerreotype. Here it is again next to a version made from the 42 resealed individual daguerreotypes. Note that the new image shows the sitters facing in the opposite direction from the original. However, because of the nature of camera lenses in the period, the version on the right shows how they were actually facing when they sat for their photographs.

Group daguerreotype for the Class of 1852: resealed original at left and a new image created by merging the 42 individual daguerreotypes into one in Photoshop.

Row 1: Joseph Manly Clark; Mason Moore; Daniel Jay Sprague; Henry Moore; Charles Henry Payson; Fayette Maynard.

Row 2: Henry Kies; Henry Root; Edward Spalding Larned; William Bradshaw Rankin; Daniel Bliss; Ambrose Dunn.

Row 3: Elijah Shumway Fish; William Winton Goodrich; Brainerd Timothy Harrington; John Humphrey Almy; Henry Martyn Cheavens; Henry Sabin.

Row 4: George Nelson Webber; Charles Leland Porter; Orson Parda Allen; Gorham Train; Theodore Hiram Benjamin; William Grassie.

Row 5: Don Carlos Taft; James Austin Littlefield; Franklin Perry Chapin; Benjamin Easton Thurston; William Ewing Glenn; Sidney Kelsey Smith.

Row 6: Edward Phillips Burgess; George Henry Coit; William Horatio Adams; Charles Wood Kingsbury; John Fuss Buffington.

Row 7: Sylvanus Baker Roel; Austin Cary Blair; Ebenezer George Burgess; Augustus Greene Kimberly; Lewis Warfield Holmes; George Lewis Becker.

The image below can be enlarged to show more detail for each member of the class. As you can see at once, poor Henry Root’s daguerreotype (second row down, second from left) sustained more damage than that of anyone else. The Tutt Library at the Colorado College has a copy of this daguerreotype: Root must have requested two and then given one to his friend Helen Fiske, known more familiarly as writer Helen Hunt Jackson. Tutt Library’s daguerreotype looks like it’s in good shape beneath the old, clouded glass. I messed with ours a bit in Photoshop, removing what looked like a big cold sore from his lip, for example, but there’s more damage here than my Photoshop skills can fix. Perhaps sometime Tutt Library will reseal theirs and then we’ll have a clear view of Henry.

Class of 1852, large file, arranged in the order of the original group daguerreotype.

I loved every moment of this project and wish we had sets of daguerreotypes for every mid-nineteenth-century class. My one regret, though, was that I was unable to locate a photograph of any kind for George Dudley, who commissioned the group daguerreotype and who is probably also responsible for our having the individual ones. As I noted in my previous post on the subject, Dudley chose to have Austin Cary Blair in the photograph rather than himself — a nice gesture considering that Blair died in 1854 and this is probably the only photograph of him. On the other hand, Dudley himself died in 1860, and while there may be a photograph of him somewhere, we have yet to see it.

A word about daguerreotypes: “First, do no harm.” If you’ve inherited or purchased daguerreotypes, you shouldn’t attempt to reseal them unless you’ve had some training. I was lucky to have some training with Mike Robinson of Century Daguerreotypes, but I’m still practicing and working on my technique. It’s not that it’s particularly difficult to reseal a daguerreotype, but the photographic plate itself is extremely fragile – if you touch it, you scratch or wipe off the image – and it’s too easy to do permanent damage. Additional information about daguerreotypes may be found at the Daguerreian Society website, especially at their faq page, as well as at other sites via a simple search.