Such names as Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Paderewski, Grieg, Debussy, Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, and Hindemith are probably familiar to WQXR listeners. But did you know that, like WQXR, they all used advanced music-playback technologies?[i] Dear reader, read on.

It’s a short walk from WQXR’s current studios in lower Manhattan to the corner of Church and Leonard Streets. That’s where the first purpose-built opera house in the United States opened in 1833. It was created by Lorenzo Da Ponte, who also wrote the words to some of the world’s most famous operas: The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte.[ii]

The music for those three operas was written by Mozart, who also wrote music specifically for playback on automated mechanical organs. Beethoven wrote the first version of his Battle Symphony for the panharmonicon, an automated mechanical orchestra.[iii] And, long before either of those musical masters (or anyone else named in the first paragraph) was born, Handel had already been programming automated musical playback devices.[iv]

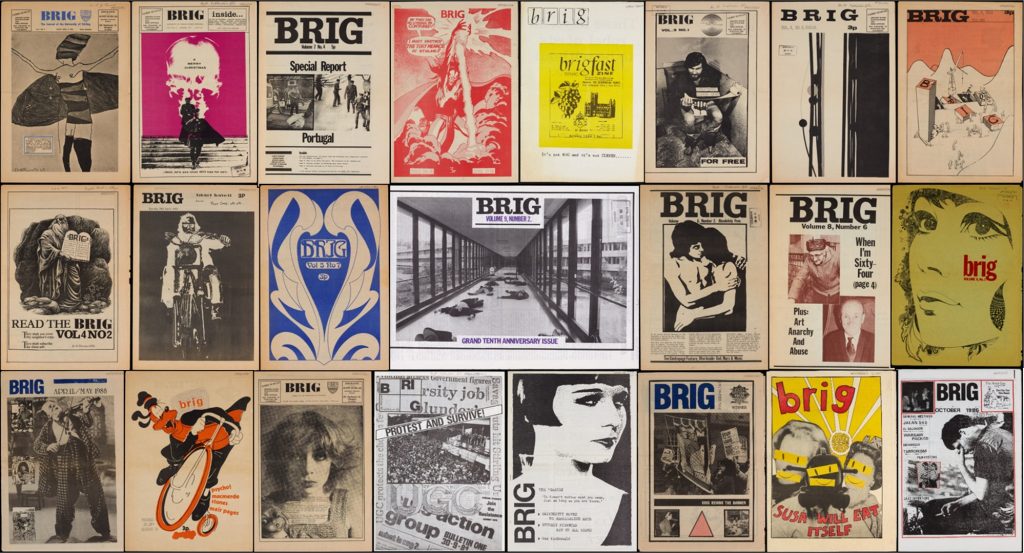

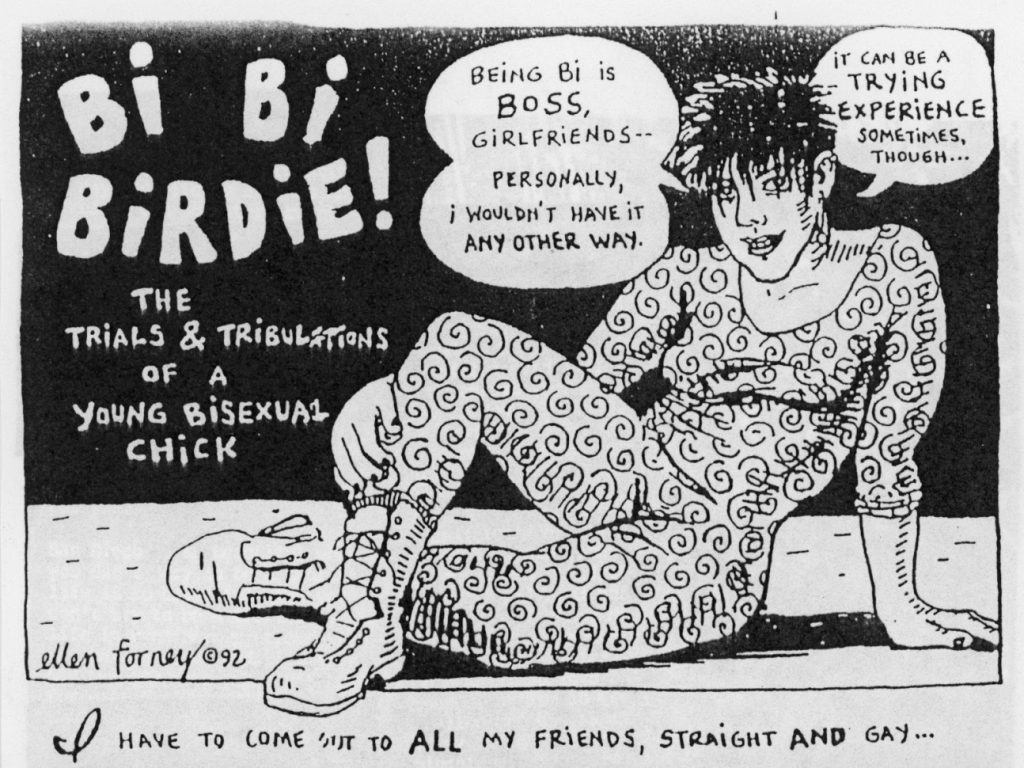

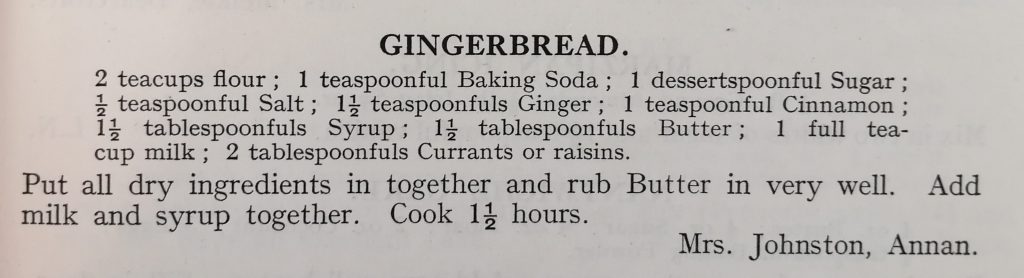

John V. L. Hogan from the 1938 Radio Annual

(WQXR Archive Collections)

As for WQXR, it was born (as W2XR) in 1929, after the inventions of the phonograph and the gramophone, which not only played music but could also record it. W2XR began as an experimental television station, and its founder, John V. L. Hogan, would sometimes play classical music records from his collection to accompany the image transmissions.

When the Federal Radio Commission made special high-fidelity channels available, Hogan got one of the first. Unfortunately, his old music discs couldn’t offer fidelity matching the new transmissions. To remedy this, Hogan and his engineer, Al Barber, obtained special “transcription” disc recordings and played them on “extended-range” turntables, with different audio filters inserted in the circuitry to match what was being played. There was also a live piano.[v]

The piano was soon joined by more instruments and musicians playing them; for many years, WQXR had an in-house string quartet, which made recordings available to the public.[vi] The station also started “cutting” recordings on 16-inch lacquer discs.[vii] But disc recordings still left much to be desired. They had a limited capacity – not enough to capture even just the first movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 – couldn’t be edited, and were susceptible to noise and distortion caused by dirt and warping.

Today, when every smartphone can record and play music using semiconductor memories, it might be hard to imagine that sound recording was difficult in the 1930s, but it was. Semiconductor memories didn’t exist. Besides mechanical discs, the only options for audio recording seemed to be optical, as in a movie’s soundtrack, or magnetic.

The classical music for the 1940 movie Fantasia was recorded optically on film by the Philadelphia Orchestra at their home in the Academy of Music. But only a few reels at a time were permitted inside lest they burn down the building. The nitrocellulose base of the film was considered an explosive.[viii] Film also had to be developed before the sound could be played.

Magnetic recording of sound had been proposed by the 1880s and was demonstrated at the Paris World’s Fair in 1900.[ix] The original recording medium was a steel wire, which could be magnetized, demagnetized, and re-magnetized; it could also be cut and then tied, soldered, or welded together for editing. It seemed to have everything – except sound quality. It wouldn’t be until after World War II that magnetic tape recording, with its higher fidelity, would be introduced to the U.S.

Before WQXR moved to lower Manhattan, it was in midtown, and, before that, it was in Queens. Also in Queens at the time was radio engineer and inventor James Arthur Miller. Miller considered sound-recording options and came up with a unique hybrid of mechanical and optical technologies. The medium was a multilayer film that a stylus could cut into. After the cutting or carving into the opaque upper layer, the result looked like a variable-area photographic soundtrack that could be played optically. It required no chemical development, so it could be played immediately after recording. And it could be spliced for editing much the same as motion-picture film. Best of all, it had the highest sound quality of any recording medium available at the time.[x]

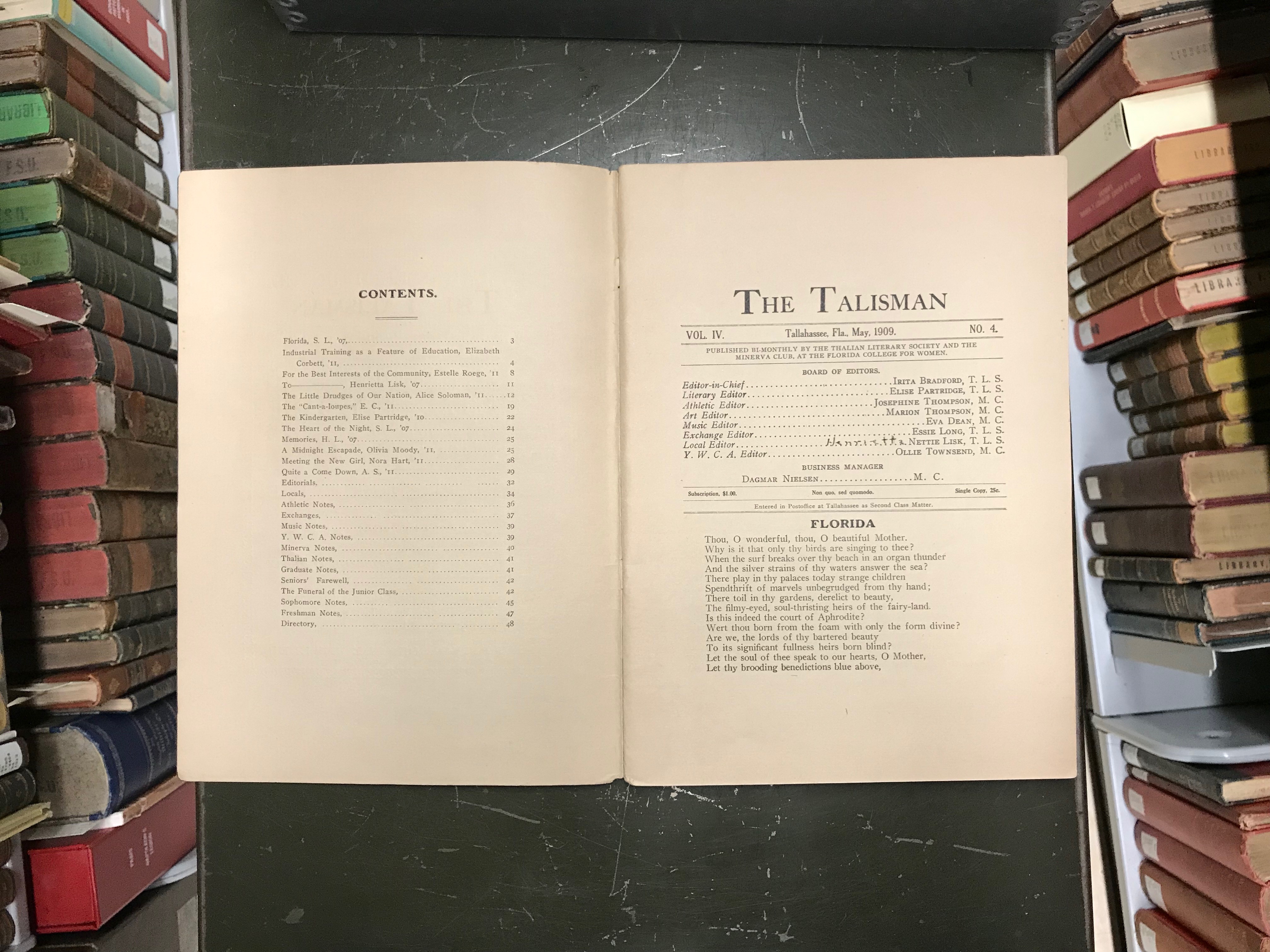

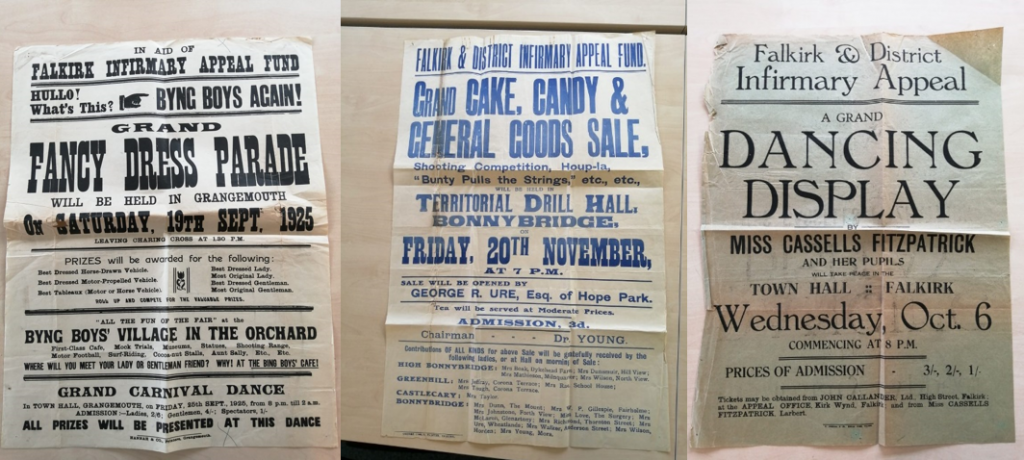

Detail photo of the Phillips-Miller Machine.

(Phillips Technical Review, March 1939)

Miller made a deal with the Dutch electronics manufacturer Philips to commercialize the product, and what became known variously as the Philips-Miller recording system, Philimil, Millerfilm, or Millertape was adopted by European broadcasters in the mid-1930s.[xi] In the United States, in 1938, WQXR was the first radio station to use the high-fidelity format, playing a BBC recording of Carmen.[xii]

After WQXR proved the utility and quality of the format, the Philips-Miller system seemed poised to sweep through the American broadcasting industry. NBC used it to record one of its programs, and high-power stations WOR in Newark and WTIC in Hartford installed the equipment.[xiii] By the beginning of 1940, another 13 stations of the Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS) had also adopted Millerfilm.[xiv] Even the background-music service Muzak used it, for “wide-range, high-fidelity sound [that] was superior to any on radio.”[xv]

Unfortunately, once the film was cut by a stylus, it could not be re-recorded, and Philips was the only source of uncut reels. Just months after the MBS stations installed Philimil reproducers, Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands, and the supply was cut off. In Germany, meanwhile, researchers had been working on a form of magnetic sound recording using neither wire nor steel bands but coated film or tape. Instead of the coating being an opaque layer that could be cut into, however, it was a layer of iron particles that could be magnetized. When World War II ended, magnetic tape recording technology was imported to the United States and swiftly developed to higher fidelity.[xvi]

What about those semiconductor sound-recording memories in smartphones? When they get filled up, they’re often archived to “the cloud,” where the information is stored on the latest generation of, yes, magnetic tape.[xvii]

_______________________________________________

[i] Hope Lourie Killcoyne, editor, The History of Music, Chicago & New York: Encyclopædia Britannica & Rosen Publishing, 2016, p. 71

[ii] Joan Acocella, “The life of the man who put words to Mozart,” The New Yorker, January 8, 2007, pp. 70-76

[iii] Killcoyne

[iv] Tessa Murdoch, “Time’s Melody,” Apollo, November 2013, p. 80

[v] Bill Jaker, Frank Sulek, & Peter Kanze, The Airwaves of New York, Jefferson, NC & London: McFarland, 1998, p. 169

[vi] Andy Lanset, “The WQXR String Quartet,” October 16, 2018, < https://www.wnyc.org/story/wqxr-string-quartet/>

[vii] “Back in the Day: Artifacts through the Ages,” WQXR Features, Sep 28, 2011, <https://www.wqxr.org/story/161452-back-day/>

[viii] William E. Garrity & Watson Jones, “Experiences in Road-Showing Walt Disney’s Fantasia,” Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, v. 39 n. 7, July 1942, p. 9

[ix] David L. Morton, Jr., “The Invention of Magnetic Sound Recording,” Sound Recording: the life story of a technology, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006, pp. 50-54

[x] Russell Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business, volume 3, New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 140

[xi] Michele Hilmes, Network Nations: A Transnational History of British and American Broadcasting, New York & London: Routledge, 2012, p. 131

[xii] Jaker, et al., p. 170

[xiii] “Transcriptions,” Broadcasting, August 1, 1939, p. 53

[xiv] “Kyser MBS List,” Broadcasting, January 15, 1940, p. 24

[xv] Sanjek, p. 168

[xvi] Nick Ravo, “John Mullin, 85, Whose Magnetic Tape Freed Radio Broadcasters,” The New York Times, July 3, 1999, p. B7

[xvii] Kayle Hope, “Tape is here to rescue big data,” Quartz, February 28, 2019, <https://qz.com/1561878/google-amazon-and-microsoft-turn-to-magnetic-tape-storage-technology-to-back-up-their-clouds/>