From the February, 1944 WQXR Program Guide.

Dr. Edman, Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University and known for his many books, including the popular Philosopher’s Holiday, is one of WQXR most ardent fans. This philosophical reaction to music is one which we feel sure is shared by many of our listeners.

The fabled “discerning reader” will detect an echo in the title of this essay. The implied allusion to Proust is intentional. The whole of Proust’s great work is a monument to memory and a creative exercise in it. The recollection of a moment of sensation of the author’s childhood, the taste of a small cake dipped in tea, is the evocation of that complex structure of “time regained” which is Proust’s long novel.

Among the things that the narrator remembers with different coloring and contexts at various periods in his life is “the little phrase” of the imaginary composer. Vintueil, thought by many to be César Franck. “The little phrase” appears and reappears in the composer’s work, now simple and unadorned, now embroidered, recast, reinforced, extended, and enriched with a thousand variations of harmonic and contrapuntal ingenuity. “The little phrase” reappears in the narrator’s life, frightened with all the cumulative poignancies of the past and fresher urgencies of the present, until it becomes a focus of life itself, the signature of the listener’s deepest feelings and ultimate character and destiny.

Music has, for all of us, its special “little phrases.” Listening becomes for us, especially the listening to quite familiar music, remembrance of themes past. No account of analysis of musical experience can be considered completes which neglects these overtones of reminiscence, these obbligati of association, often far from explicit, which accompany and lend depths of emotional coloring to what is, on the surface of consciousness, the most objective and puristic listening. Tune in on Symphony Hall some evening and hear the triumphant grand theme of the César Franc k symphony. It seems less grand, perhaps, than it used to, and less original than once you thought. But it has regained the pathos of time and recollection. It has the feeling of something heard long ago, in your youth, perhaps, when it and everything, was fresh, and rapture in clear brasses seemed exactly the note for life just beginning its hopes and its own possible victories. Or you hear the slow movement of Mozart’s piano concerto, K. 467, and the haunting finality of the breathless, quiet, repeated beat of the single notes of the piano above the almost hushed orchestra at the close. That perfect peace, that peaceful perfection, are still what they were, but enriched now by the memory of their first discovery, played by Schabel, perhaps in Carnegie Hall, or in Queen’s Hall, London, now bombed out of existence. Or they are colored, too, by the many occasions when perhaps you played it on records yourself, for a friend now in Africa, or in the South Pacific, for another who wondered what you saw (or heard) in Mozart, or for a group of people, some now dead, or gone in any case out of your life. Or there sounds the hunting horn theme of King Mark in Tristan. What a melee of memory is telescoped into that, of the days when Tristan seemed pure ecstasy and the times when much of it seemed pure tripe, and of the damage done to your enjoyment of Wagner by pictures of Hitler at Bayreuth, or Wagner’s accounts of himself.

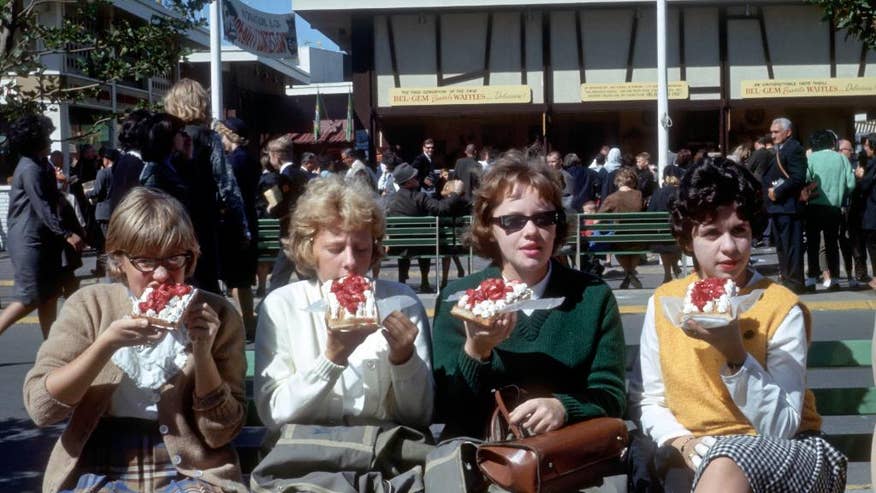

It may be the instant’s pause after the long architectural introduction, followed by the felicity of the clarinet in Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto, mixed up perhaps with the memory of Benny Goodman playing non-Mozart at the San Francisco Fair. Or hints of remembered clarinet passages of Gluck and Brahms, so that this melody transmutes into pure essence all the clarinetism, as it were, of the history of music.

Many themes you can scarcely hear as music at all, music pure and clear, so much they are qualified by conventional associations, the Wedding March, Handel’s Largo as heard at a funeral service, Tchaikowsky’s Andante Cantabile.

But the subtlest effects of memory-in-music are not those of definite labelled associations. They are the effects of purely melodic memory, so that a tone itself is it is in the context of what has gone before, what now reappears in the violins with its previous life in the horns subtly recollected in it. Musical attention is a half-listening to what is already an ancient legend to the ear. And the tones have become tinctured with our own past, the patterns of sounds blended with the poignancies of biography, so that what we hear now is our whole history, and notes themselves become the wordless notebooks of our emotional lives.

It is because in music we are most intimately stirred to remembrance that listening is so poignant a pleasure. Hearing is so often rehearsing, and “heard melodies” are echoes of things unheard and unforgotten that are awakened by themes, past, now, memory rich, present acutely once again.

to cause a sensation on its U.S. debut at the ’61 Seattle World’s Fair, but in New York it, um, fared better: MariePaule Vermersch, now 66, remembers helping her parents (her mother, 95, still lives in Queens) dish out the delicacies to endless lines of hungry Fair-goers for days on end.

to cause a sensation on its U.S. debut at the ’61 Seattle World’s Fair, but in New York it, um, fared better: MariePaule Vermersch, now 66, remembers helping her parents (her mother, 95, still lives in Queens) dish out the delicacies to endless lines of hungry Fair-goers for days on end.