From the July, 1942 WQXR Program Guide:

Mr. Ewen is an authority on musical history, and the author of several books including The Man With the Baton, Musical Vienna, and Music Comes to America.

Perhaps the best barometer of the development of musical culture in this country is provided by the changing tastes of our concert audiences.

A century ago, American musical audiences did not like recitals by single artists. They preferred something of a variety show in their concert halls, featuring several different performers, possibly an orchestra and a chorus as well, together with one or two spectacular entertainment numbers.

An artist like Henri Vieuxtemps, for example, was forced to appear on a program that included a concertina performer who crushed his instrument on his nose or forehead. Theodore Thomas, then a violinist, was included in a concert together with a “prodigy,” Master Marsh, whose art consisted in playing on two drums simultaneously. A serious performance by a single artist had no appeal whatsoever. As late as 1873, Anton Rubinstein startled his American manager by suggesting a series of solo recitals. “Solo recitals?” cried the manager, “Who would attend a solo recital?”

When American audiences did attend a recital, it was usually not for the music but to witness a circus show. Louis Gottschalk, generally considered the first great American pianist, would go through the routine of a matinee idol. He would come on the stage, meticulously dressed even to gloves, would then remove his gloves fastidiously and throw them into the audience as precious mementos. He would play his programs with extravagances of body motions and facial gestures that thrilled his audiences, who admired his showmanship much more than his art.

Frequently, concert recitalists went to even greater excesses. Hatton, a concert pianist, had sleigh bells attached to his ankles so that he might accompany a composition describing a sleigh ride with actual bell sounds. Dwight’s Journal of Music reported how successful this number was with audiences of the times. Another pianist, Volovski by name, guaranteed to play at his concerts no fewer than four hundred notes in one measure. Leopold Meyer promised to perform certain compositions not only with his fingers, but with his elbows, fists, and even with a cane. Ole Bull sometimes played on a flattened fiddle bridge. Even a fine musician like William Mason was compelled to resort to tricks. His tour de force was playing Old Hundred with one hand and Yankee Doodle with the other.

The tastes of audiences were plebeian, and even great artists had to cater to them. Thalberg used to feature his meretricious potpourris from the operas endlessly; some of his programs were compiled exclusively of these fantasias. Vieuxtemps used to play the Arkansas Traveler and Money Musk frequently; Wilhelm and Rubinstein variations on Yankee Doodle; Ole Bull, The Mothers Prayer and the Carnival of Venice. Even the greatest opera singers of the time had to clutter their recital programs with such favorites as Home, Sweet Home and Comin’ Through the Rye.

Audiences of a century ago, or even half a century ago, were not attracted to chamber music. The attendance at concerts by such pioneer chamber-music ensembles as the Eisfeld Quartet, the Mason-Thomas Quartet, the Dannreuther Quartet, and later the Kneisel Quartet, was so small as to discourage even a hardened musician.

William Mason used to stand on the corner of Union Square on the morning of his chamber music concert, personally distributing handbills in the hope that he might attract some passerby to his performance. Even then, the hall was three-quarters empty. “Mr. Mason forgets,” commented a critic of the Daily Express (March 26, 1856) in explaining the failure of the Mason-Thomas concerts, “that it is chiefly for the performer, and not so much for all this aspiration in music, that a majority of the people go to a matinee.”

The Kneisels too, in the early history of their performances, were frequently taken to task by the press for failing to feature popular music on their programs, and insisting on catering to such an esoteric public. And during the early years of the Flonzaley Quartet, the concert halls in which they played were so consistently deserted that one of their members suggested coming out on the stage on bicycles. “Perhaps then,” said the musician wistfully, “the audiences will notice us.”

Kneisel String Quartet, circa 1890.

Needless to say, symphony audiences have also undergone a radical change. A century ago, a symphony was such a formidable dose for an audience that many orchestras throughout the country interpolated light salon numbers between movements. At the first American performance of Beethoven’s First Symphony (in 1820 at Philadelphia), light vocal and solo numbers were included between the movements to allow for variety and entertainment. Such practice continued well into the century. Even then, audiences did not like symphonic music, preferring light concert numbers, waltzes, potpourris–and, above everything else, sensational pieces.

The Germania Orchestra, which toured America in the 1850s, included in its repertoire theatrical numbers called The Railroad Gallop. During the performance, a toy locomotive ran on the stage puffing smoke. The English-French conductor, Jullien, when he visited this country with music by Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, and Mendelssohn, scored his greatest sensation with a number called The Fireman’s Quadrille. During the performance, firemen came on stage with full fire equipment and poured water on a simulated fire; then they marched off the stage as the composition came to its close. Theodore Thomas, too, resorted to histrionics in his performances, early in his career as a conductor. In his open-air concerts in New York, he would perform a polka, with the performing flutists concealed in the trees.

We contrast the music audiences of America’s yesterday with those of today, which demand the best in every form of the musical art. Only then do we realize to what extent America has grown as a musical country.

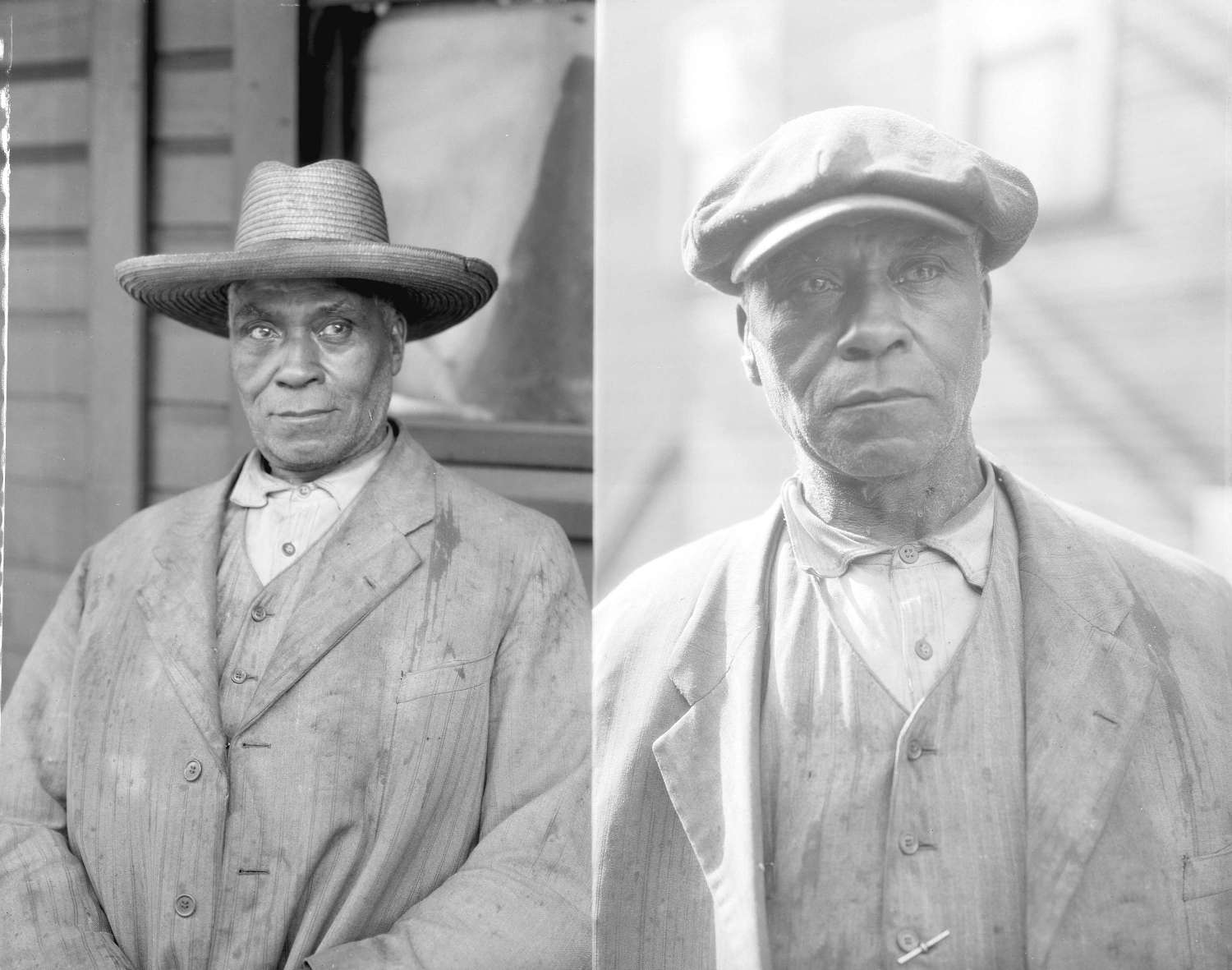

Portrait of the Germania Musical Society, a group of musicians originally from Germany who toured in the United States, 1848-1854.

H. Earle Johnson. “The Germania Musical Society.” Musical Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Jan. 1953)/Wikimedia Commons