Ted Cott was just 17 in 1934 when Seymour N. Siegel hired him to be the station’s Drama Director. Cott had been a volunteer doing weekly radio plays with other City College students when his promising work came to the attention of Mayor La Guardia, who insisted ‘the young man’ be hired. La Guardia had only been Mayor about six or seven months and had campaigned to shut WNYC down, believing it was a waste of money. But Siegel had engineered a stay of execution and needed to bring in some fresh ideas and talent to further convince La Guardia that the station was worth keeping. Since there was no equivalent civil service post at WNYC’s parent agency, the New York City Department of Plant and Structures, Cott was hired as a ticket taker for Staten Island Ferry and reported for work at WNYC. [1]

Once there, Siegel promptly bolstered the teenager’s immersion into radio drama. According to Cott, the Assistant Program Director had been looking at a book of plays, whose cover warned against them being performed for profit without the permission of the copyright holder. Reasoning that WNYC was non-profit and had clearance from someone in the city law department, Siegel gave Cott the green light. The teenager began borrowing multiple copies of various dramatic works from a host of neighborhood libraries so that the WNYC Radio Playhouse was well supplied. “If you should ever find some old plays in public libraries that are marked up, you’ll know who did it,” Cott later said. After a while radio drama reviewers took notice and liked what they heard. The Shubert Organization got word as well, only they were less than thrilled and called Mayor La Guardia to say their plays were being produced without their permission. Soon afterwards, Cott’s frequent trips to the library came to an end. [2]

Given the need for original material as well as demands for more variety, Cott and his radio playhouse set to work on a weekly musical serial called On the Wings of Song. The New York Post described it as having “a flying field setting and original music,” launching on May Day 1936.[3] Throughout 1937 Cott and company’s adaptations for the radio included: Julian Thompson’s Warrior’s Husband; Philip Barry’s Paris Bound; Maxwell Anderson’s Elizabeth the Queen and Winterset; and Robert Browning’s The Barretts of Wimpole Street, the Radio Playhouse’s 210th production. Variety’s radio reviewer said the production “is distinguished by one outstanding performance, that of Ted Cott, who also did yeomanship work in adapting a piece that is not extremely palatable material for a full hour of radio consumption. As presented here, the absence of action in the play is stressed. Bulk of action is wrapped up in the harsh verbal gyrations of Edward Barrett, pater of the Wimpole Street family. It’s not enough. Probably the most arresting passages are those between Robert Browning, portrayed by Cott and Elizabeth Barrett, the part taken by Eugenia Cammer. Latter does fairly well in upholding her end opposite an ingratiating characterization by Cott…who directed as well as adapting the story, did nicely all considered, though about 4 minutes shy of his skedded [sic] time.” [4 ]

But the trade paper was less impressed with Playhouse’s production of Irwin Shaw’s Bury the Dead, which was successfully produced two seasons earlier on Broadway. “While the play carried a telling punch and considerable force as an anti-war argument, it seemed not as well suited to radio as to the stage. However, that may have been the fault of the adaptation, direction or playing–or a combination of all three. Whatever the quality, it did make interesting fare, particularly with current headlines as a backstop.” [5] The play was part of an anti-war series called We the Living, comprised of Hans Chlumberg’s Miracle at Verdun, Robert Sherwood’s Idiot’s Delight, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Humphrey Cobb’s Paths of Glory.

The New Radio Drama

By January 1938 Cott began writing new material based on important but little-known Americans and historical events and places. The 39-script series, America’s Hours of Destiny, was reportedly well received by radio drama critics and was picked up for national distribution by the National Park Service, who wrote, “It has proved of especial interest to colleges in connection with their radio and dramatic work.”[6] Cott’s unsung heroes and episodes from the past included a lot national parks, monuments, and battlefields. Among them: Zion, Yellowstone and Acadia National Parks, Major L’Enfant and the nation’s capitol, the Statue of Liberty; and Death Valley Monument. And if that wasn’t enough, in early 1938 Film Daily reported that Cott would also be adapting movies for the radio beginning with Monogram’s Boy of the Streets, with Broadway actor Charles Bellin taking the role played by Jackie Cooper in the film. [7]

Cott had an interested and sympathetic ear in The Brooklyn Eagle‘s radio columnist Jo Ranson, who outlined the workings of the WNYC Radio Playhouse and its workshop, “formed for the purpose of carrying on experiments in the writing and production of radio drama embodying new departures in drama technique.”[8] Ranson wrote of the regular Friday evening meetings at WNYC where Cott and his crew hashed out scripts debating the merits of various narratives, dialogue and production techniques:

“Too many sound effects in your script,” says one. The author keeps silent but some one else rushes to his defense. “I don’t agree. I think he’s made very effective use of sound.” From all sides the battle continues. “The dialogue is stilted.” “Characterizations weak,” “Ending lacks punch.” The author defends himself sometimes; on other occasions criticizes his own work. Finally, the most pertinent criticisms are summed up and the playwright is told to rewrite his script. In two weeks, three weeks, even two months, the script will be ready for production by WNYC’s Radio Playhouse Experimental Workshop…Cott serves as chairman for the meetings and acts as coordinator between the actors and playwrights. He’s also written some of the best Workshop shows himself.” [9]

In 1938 Cott and the Playhouse initiated an Ibsen cycle of dramas which included A Doll’s House. They also embarked on The White Legion, a series by former newspaperman Jack Bishop, who had spent time as a researcher for the popular radio show Gangbusters. Weary of showing how criminals worked, Bishop focused the series as a showcase for police and federal gang-busting activities and tactics in New York. The dramas reportedly won praise from penologists and parents.

Less than a month after Orson Welles was on the front page of the nation’s papers for the CBS War of The Worlds broadcast, Cott made it to the front page of The Brooklyn Eagle under the headline: “Poison Gas Rocket Lands Here, But Fails to Panic Radio Fans.” Cott had decided to produce a radio play in which a man and woman turn on their living room radio and hear reports on a foreign power sending a lethal poison gas rocket into the United States. When their friends arrive, the couples panic and plan an escape by airplane, but the rocket lands first. One can be sure Cott’s foley man provided sound effects to paint an the appropriately horrific picture for the mind’s eye. Still, the paper reported “listeners took it in stride” with neither police in Manhattan and Brooklyn nor WNYC receiving a single call of panic or complaint. “Mr. Cott explained later that the radio group had no fear that the fantasy would be taken for the real thing. ‘The audience should be trained against panic by this time,’ he said.” [10]

At the end of each year Cott adapted for radio the Mayor’s annual report, New York Advancing. This dramatization of the previous year’s civil service highlights was called New York Advances and was among Cott’s most challenging productions since it involved La Guardia playing himself and predictably telling everyone else what to do and how to do it. But Cott would have none of it.

“Finally I stopped it and I said, ‘Look, you may be the Mayor of New York, but right now I’m the mayor of this studio, and to me you’re just another actor in this show. Only somebody very young could have said this to [him]. “He said, ‘You’re right,’ and sat in the corner. He was just marvelous every year on this thing.” [11]

Ted Cott could also be counted on as a reporter for the News Department. He recalled one especially insane episode covering the July 14, 1938 parade celebrating Howard Hughes and his record-breaking flight around the world. With a portable shortwave transmitter, Cott and colleague Dick Pack were on top of the WNYC remote truck feeding the studio a constant stream of color about the parade.

“Everything was fine up to around 8th Street, and suddenly, instead of going about 10 miles an hour, they decided we’re going to go at 40 miles an hour. Standing on top of a truck with a round roof is not the most pleasant place for such an activity. We finally were forced down onto the top of the roof, lying flat on our stomachs, with the misguided notion that ‘the show must go on.’ We kept describing all these things, and finally got off at 61st Street, very tense and very bruised, very shaken and nervous –but very proud.” [12]

Unfortunately, no one heard them. The shortwave reception was so bad Radio Master Control cut them off around 6th Street. We do, however, have the following brief example of Cott’s reporting acumen from Election Night, 1938 at Times Square.

Radio’s First Music Quiz Show

About the time Cott risked his life covering the Howard Hughes parade he had also been doing announcing shifts during the weekly WNYC broadcast of City Council meetings. Whenever the session ended early, he filled in the remaining time by playing records and commenting informally about the music. It wasn’t long before the shift included a quiz on serious music with questions solicited and supplied by listeners, who mailed them in by the hundreds. By late 1938 Symphonic Varieties was a regular and popular WNYC quiz show done before a live audience.[13]

The quiz pitted a professional musician against a well-informed layman in a good-natured contest of musical knowledge. Among the musical geniuses on the show were David Randolph, a regular WNYC host by 1946, Jonathan E. Sternberg, an NYU Senior who is now known as the distinguished Maestro Sternberg. Since they were on a shoestring budget to begin with, no prizes were offered. When Cott left for CBS about a year later, he took the show with him, where it became known as So You Think You Know Music. In 1940, the liberal tabloid PM commented that the show also landed Cott in Who’s Who in Music even though he couldn’t read a note.[14]

[The first So You Think You Know Music from June 4, 1939]

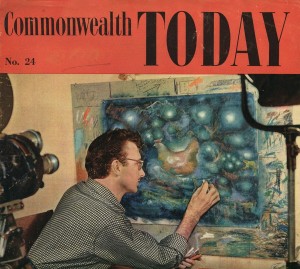

Cott also produced and emceed the RCA Victor Sounding Board over WEAF and What’s the Good Word over Mutual Radio into 1943. He was then hired by the independent WNEW to be their Vice President of Programming for seven years. Afterwards, he left for NBC, where he was manager of WNBC Radio and WNBT – TV. Cott later was Vice President for National Telefilm Associates, operating WNTA Channel 13 in New York before it was WNET. He had been President of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences and was the author of several media related books. Ted Cott died at the age of 56 in June, 1973.

Ted Cott soon after he left WNYC for CBS in 1940. (WNYC Archive Collections)

___________________________________________________

[1] “Reminiscences of Ted Cott,” 1960 and 1961, on pages 4-8 in the Columbia University Center for Oral History Collection (hereafter CUCOHC).

[2] Ibid., pg. 14.

[3] The New York Post, April 28, 1936, pg. 34.

[4] “Barretts of Wimpole Street,” Variety, June 30, 1937, pg.39.

[5] “Bury The Dead-WNYC Drama,” Variety, September 15, 1937. pg. 36.

[6] The National Park Service, The Regional Review, October 1938, Vol 1., No. 4.

[7] The Film Daily, January 22, 1938, pg. 1.

[8] Ranson, Jo, “Radio Dial Log,” The Brooklyn Eagle, February 5, 1938.

[9] Ranson, Jo, “Radio Dial Log,” The Brooklyn Eagle, June 25, 1938, pg. 18.

[10] “Poison Gas Rocket Lands Here, But Fails to Panic Radio Fans,” The Brooklyn Eagle, November 27,1938, pg. 1.

[11] “Reminiscences of Ted Cott,” pg. 17.

[12] Ibid., pg. 16.

[13] Scher, Saul Nathaniel. “Voice of the City: The History of WNYC, New York City’s Municipal Radio Station, 1924-1962,“ NYU Ph.D. Thesis, 1965. pgs. 199-200.

[14] “Champagne Music Quiz Gets a Beer Sponsor,” PM September 25, 1940, pg. 13

Special thanks to Mary Marshall Clark, Director of the Columbia University Center for Oral History and her staff for their assistance. Thanks too to James and Jonathan Cott, who, by the way, hosted a program on WNYC in the early 1960s called, Music Not to Read By.

The clinicians and scientists at this meeting were grappling with many unknowns at the time, and their relief over the disease’s downward trend at the time is palpable, if cautious. Issues ranging from clinical recognition of the disease to vaccine efficacy are discussed. Dr. Harry M. Rose perhaps summarizes it best, declaring that “one of the astonishing things indeed is that the epidemic proportions were not even larger,” while later advising to “hope and pray” that the number of incurable cases does not grow. Although there is much advice given on clinical treatment and immunization guidelines, no one sounds snug or sure-footed —these are professionals who clearly have experienced a few rough weeks.

The clinicians and scientists at this meeting were grappling with many unknowns at the time, and their relief over the disease’s downward trend at the time is palpable, if cautious. Issues ranging from clinical recognition of the disease to vaccine efficacy are discussed. Dr. Harry M. Rose perhaps summarizes it best, declaring that “one of the astonishing things indeed is that the epidemic proportions were not even larger,” while later advising to “hope and pray” that the number of incurable cases does not grow. Although there is much advice given on clinical treatment and immunization guidelines, no one sounds snug or sure-footed —these are professionals who clearly have experienced a few rough weeks.