In my June 2013 post I mentioned several collections from and about Amherst College alumni who had careers as missionaries. In this post I want to focus on one item from one of those collections, the William Earl Dodge Ward (AC 1906) Family Papers.

Earl Ward and fiancee Dora Judd Mattoon in Turkey, ca. 1912

While listing the collection (the finding aid is here), I examined a photograph album that Earl Ward, an avid photographer, had put together to document his first trip as a missionary, from 1909-1913. Earl’s album begins with pictures he took on his way from Constantinople to Harpoot, where he was to be stationed as the mission’s accountant, with teaching duties on the side. The album also contains many photographs from the years he was in Harpoot itself, including photographs of Armenians, Turks, and Kurds going about their daily lives. Most of the photographs are small and faded, but they still beautifully illustrate life in the region. Toward the end of the album there are a few large photographs that Earl obtained from an unidentified photographer. One of them caught my eye right away – it’s a group shot, obviously commemorating an event.

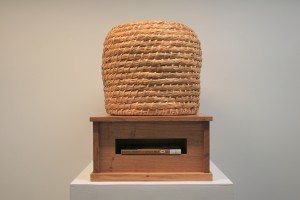

Crowd at Mezreh. Click on photo to explore in detail.

I remembered that Earl wrote home regularly, so I checked his correspondence for the period that the album suggested – from 1909 to 1913. Serendiptously – because one couldn’t expect that such a thing would exist in the first place, and have survived in the second – Earl wrote a letter to his sister Laura in which he describes this very photograph. He writes:

“Dear Laura,

“Dear Laura,

The picture I enclose is for Xmas for you. In order to get it in a good envelope, I had to cut it into 2 halfs. Match it together & mounted or simply unmounted & you get a view of the Turkish & Armenian crowd that assembled at Mezreh, a village on the plain below Harpoot & the capital of this province, to celebrate the accession of the new Sultan last April while I was in Constantinople. You will notice at the left center…a banner or rather support carrying a picture they had of the Sultan as he appeared as a young man. Now he is over 60 & looks nothing like this picture. Turkish banners wave in the air with the star & crescent on them. Turkish soldiers line the path which leads up to the barracks before which this celebration took place. Those with fezes beyond are the Turkish military schoolboys. Those nearer with funny headdresses are the regulars. In the centre stands the Governor (called a Vali) with his son beside him, the military commander, the religious leaders (in white turbans) & officers. This picture was taken by the photographer here. Notice the sea of faces & the snow on the ground.”

Keen-eyed observers will note that this copy of the photograph is not the one Earl sent to Laura — it is not ripped in half. Earl’s habit was to send carbon copies of his letters, and multiple copies of his photographs, to recipients at home, so what we have here is Laura’s copy of his letter (“answered Feb 1st, 1910″ is hers), and his own copy of the photograph.

Earl’s description inspired detailed scans of the parts he described. First, the “support”:

“…a picture they had of the Sultan as he appeared as a young man. Now he is over 60 & looks nothing like this picture”

In poking around online for information about the sultan in question, I came to wonder whether Earl misidentified the man on the banner. He understandably implies that it is the 65-year-old Mehmed V, and it would be logical to think so since the occasion at Mezreh marks his accession as sultan. However, although Mehmed V may have been young once, I haven’t yet found his youth documented in photographs anywhere online, perhaps in part because he is said by Wikipedia (in a passage repeated online over and over again) to have spent the first 30 years of his life secluded in the royal harem. Instead, the figure on the placard looks more like his predecessor (and older brother), Abdul Hamid II, as he appeared in photographs taken at Balmoral around 1867.

Abdul Hamid II.

Given these two shots taken at the same time, it seems possible that there were more taken at that session to assemble a portfolio of images. In Earl’s picture, the uniform and age of the man look the same as in the other two shots, and he stands with one hand resting on his sword. So while it seems logical to assume, as Earl did, that the man on the placard is Mehmed V, and illogical to think it’s Abdul Hamid II (especially since he had been deposed as sultan and was distinctly out of favor with the defacto rulers, the “Young Turks”), we shouldn’t take it for granted that the image we see is Mehmed V. Perhaps the citizens of Mezreh still sought to honor their former, long-serving sultan and used his picture on the banner even as they celebrated the new sultan. It’s a minor point, but it reminds us not to take primary documents at face value if other evidence suggests a different interpretation. Just because “they were there,” doesn’t mean they always got it right.

Earl also describes the governor, his son, and the military leader:

The military leader (left of center, with medals), the governor and his son to his left, with religious leaders behind them.

Still curious, I went back to a letter from Earl to his family from the month before he sent the photograph to Laura and found that he’d described the governor’s visit (and what’s more, he’d typed his letter – huzzah!):

Earl Ward to family, Nov. 24, 1909

The photograph of the governor’s visit has the appearance of a harmonious celebration — it suggests unity and common cause. However, as the letter above indicates, Earl was aware of the dangerous state of affairs in Turkey. In fact, he had arrived in Constantinople on April 19 and written to his mother at once, telling her on a postcard that “Constantinople is in the throes of a revolution. Missionaries anxious but not in danger.” By the end of the month, he had written about bullets flying over his head and the situation of the refugees after the Adana massacre. Such events would not have been all that surprising to Earl Ward, for he would have been aware of what his missionary grandmother, Isabella Holmes Porter Bliss, had reported from Constantinople during the time of the Hamidian massacres in 1894-96. Isabella’s letters are also at Amherst College, documenting the waves of killing in Asia Minor over the course of many decades.

An obvious question about this photograph is, if Earl didn’t take the photograph, who did? I haven’t yet discovered whether Earl mentions the local photographer’s name in his extensive correspondence, but online research brought up an article about a photograph, dated around 1912, of seven Euphrates College (in Harpoot) professors, six of whom had been murdered (Earl’s album contains a postcard copy of the same image). The article credits the photograph to the Soursoursian brothers: “Askanaz and Haroutune Soursourian were brothers. Each had a family and they lived in Hussenig, a large village at the base of Kharpert [Harpoot] city which was predominantly populated by Armenians… They learned photography in Tiflis, Russia (Georgia). They reputedly prepared their own glass plates and printing papers as well… Perhaps more importantly, they were the only photographers in the entire ‘state’ of Kharpert….”

It seems possible, then, that Earl’s photograph of the crowd at Mezreh was taken by the Soursoursian brothers. Perhaps future research will enable us to answer the question firmly.

Earl’s album is in the queue for digitization and will be located on our ACDC site: https://acdc.amherst.edu/. In the meantime, it’s available for viewing in the Archives and Special Collections.