This blog post is a slightly edited version of a talk I gave last Friday to our regional professional organization, New England Archivists. We have a one-day meeting in the fall, and this year it was held at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston. Our theme for the meeting was ethics in archives, and each of the nine presenters discussed collections or events that dealt with ethical challenges.

Like librarians and doctors, archivists have a code of ethics that guides our work. You can read ours here: Society of American Archivists: Core Values and Code of Ethics for Professional Archivists. Shared discussion and consideration with colleagues is an important way for us to develop and learn as professionals, especially about ethical questions, which are always matters of judgment.

Describing Archival Collections—Ethical Considerations

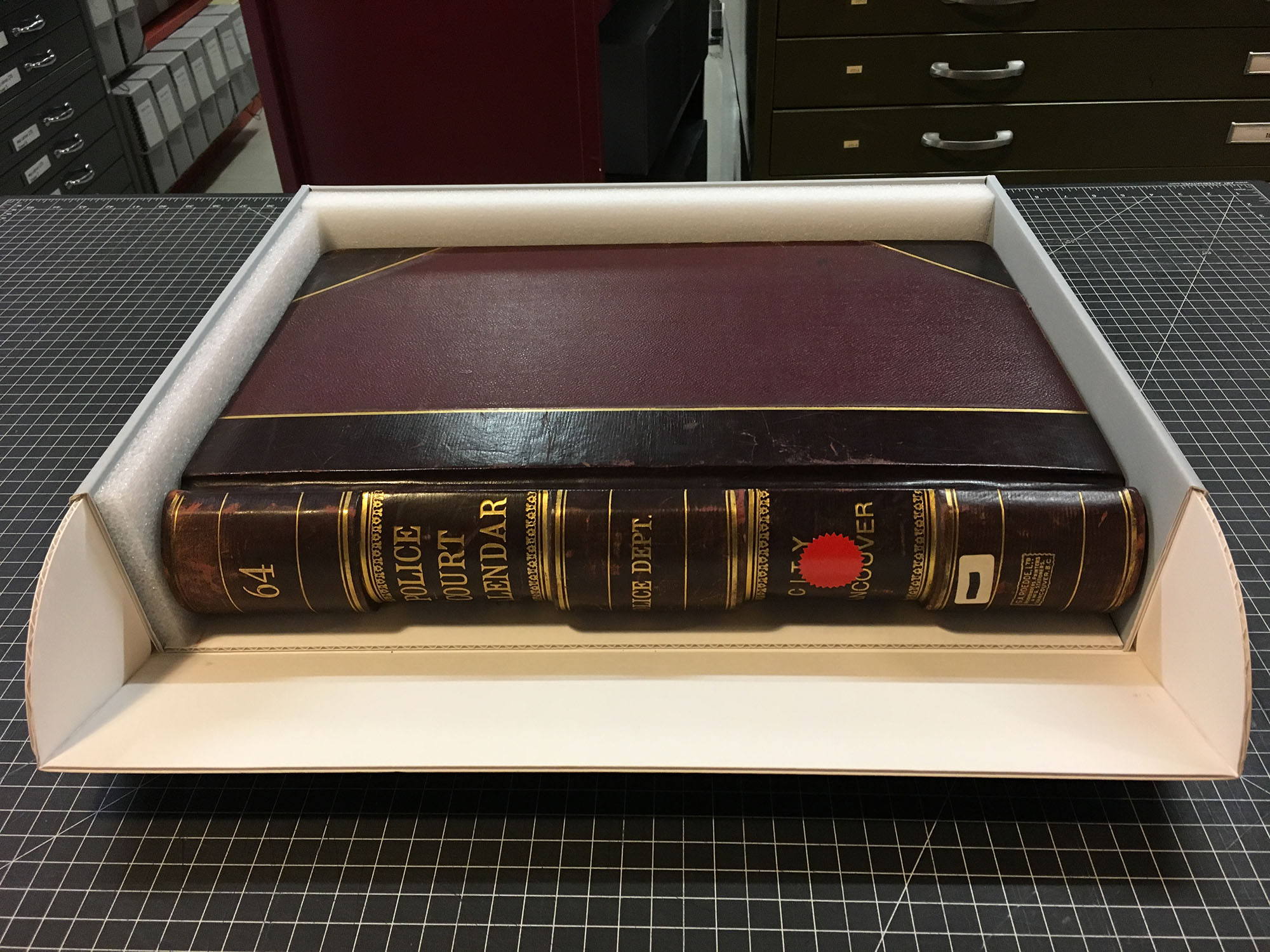

It’s hard to say no to your boss, especially when it’s your first job as a professional archivist. Reprocessing the

Frederic Brewster Loomis (AC 1896) Papers

took far more of my time and labor than either of us expected. Negotiating this collection and its ethical demands was both personally and professionally challenging. Looking back now, nearly a year later, I find that I can better trust my own ethical judgments and see more vividly the violence inherent in overly “neutral” or “objective” descriptive practices.

Replacing an imperialist, genocidal mascot–Lord Jeffrey Amherst, who proposed gifting smallpox-infested blankets to Native communities–with a huge purple mammoth was an excellent idea. The 20-ft tall inflatable version in the right-hand image above greeted our new first year students this fall.

Why do we have a mammoth?

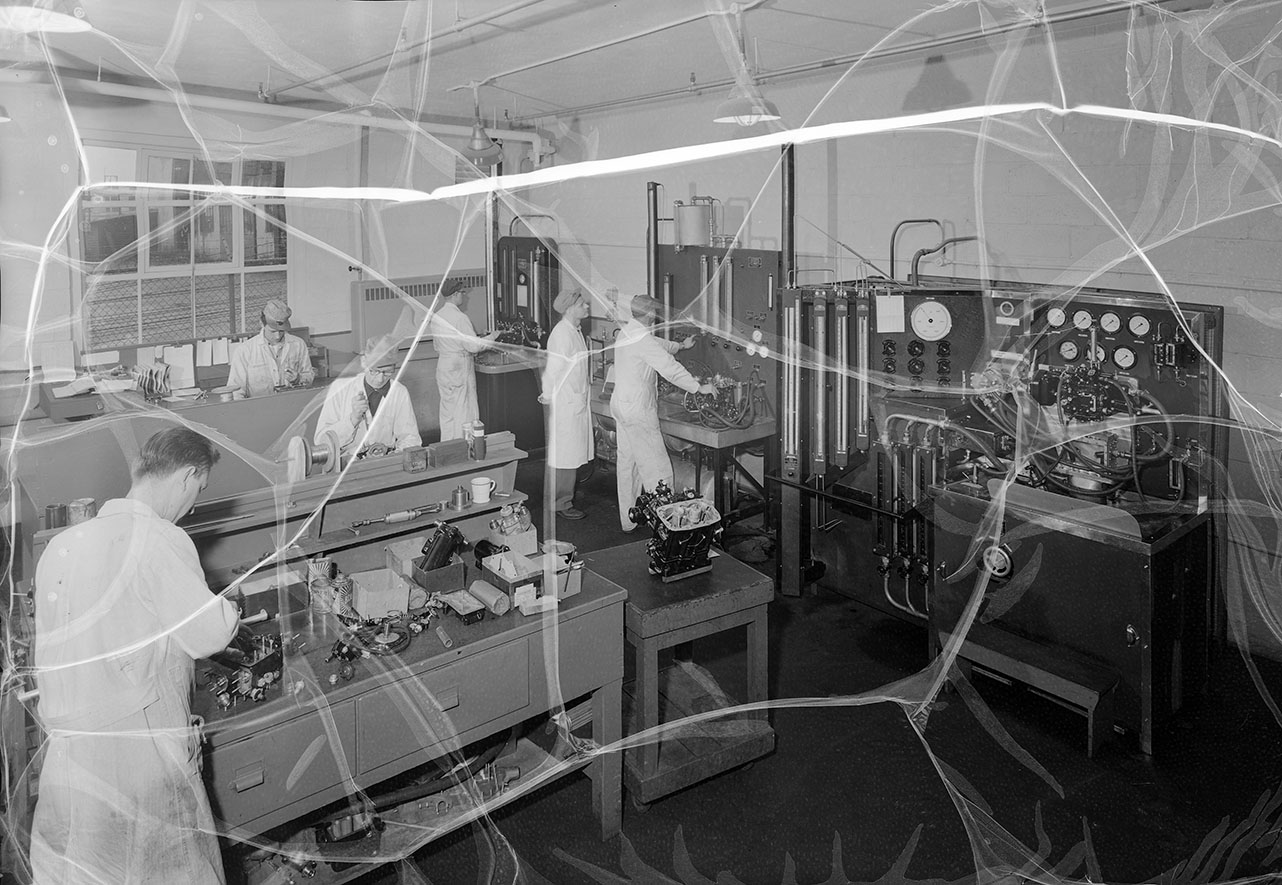

This guy, Frederic Brewster Loomis. He’s the one on the left.

His friends called him “Mud Puppy.” He’s standing in the workroom next to the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) fossil skeleton he recovered in 1923 and 1925.

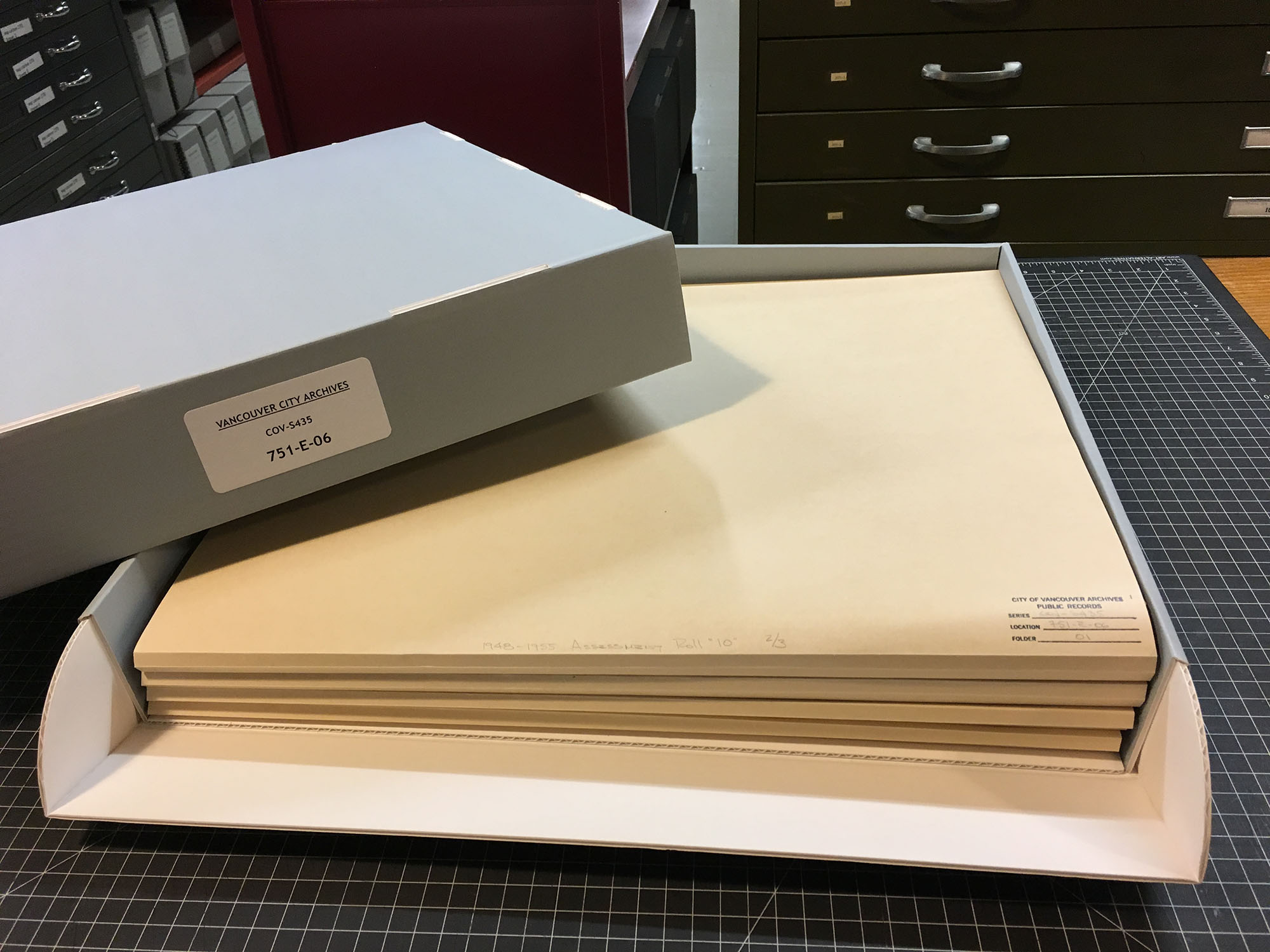

The new mascot meant that this paleontologist’s two boxes of papers were now a priority to reprocess, with an eye towards eventual digitization. This seemed to be an easy job for the new archivist (me). But when I began reading Loomis’s accounts about the 1923 and 1925 digs in Melbourne, Florida,I realized that in addition to mammoth fossils, Loomis recovered human remains and artifacts.

Suddenly, this collection was not as easy as I had expected it to be.

As I continued processing, I began noting the locations of Loomis’s worksites, which could be vague, noted only by a creek or town name. I also began looking for more context in museum and anthropology literature, focusing on the 1990 North American Graves Repatriation and Protection Act (NAGPRA), and the ethical responsibilities of institutions holding Indigenous bodies and artifacts.

NAGPRA reviews and inventories had in fact been conducted for the holdings of the Beneski Museum of Natural History, Amherst’s science museum. Loomis’s work had focused on museum collection growth, and his shipments of fossils became a large percentage of the holdings.

I initially assumed that the non-human fossils were not an ethical concern, until I remembered SUE. The T. rex fossil at the Field Museum (Chicago, IL) had been purchased at auction for $8 million after protracted court cases were required to determine ownership after the 1990 dig on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation.

I initially assumed that the non-human fossils were not an ethical concern, until I remembered SUE. The T. rex fossil at the Field Museum (Chicago, IL) had been purchased at auction for $8 million after protracted court cases were required to determine ownership after the 1990 dig on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation.

The Field Museum does science outreach and education through SUE’s Twitter persona, @SUEtheTrex.

The museum’s site about SUE discusses how they came to the museum, and what paleontologists have learned about tyrannosaurus rex.

The non-human fossils were valuable resources, and their removal to Amherst College was not harmless. For more analysis, I recommend Lawrence Bradley’s book Dinosaurs and Indians in the references.

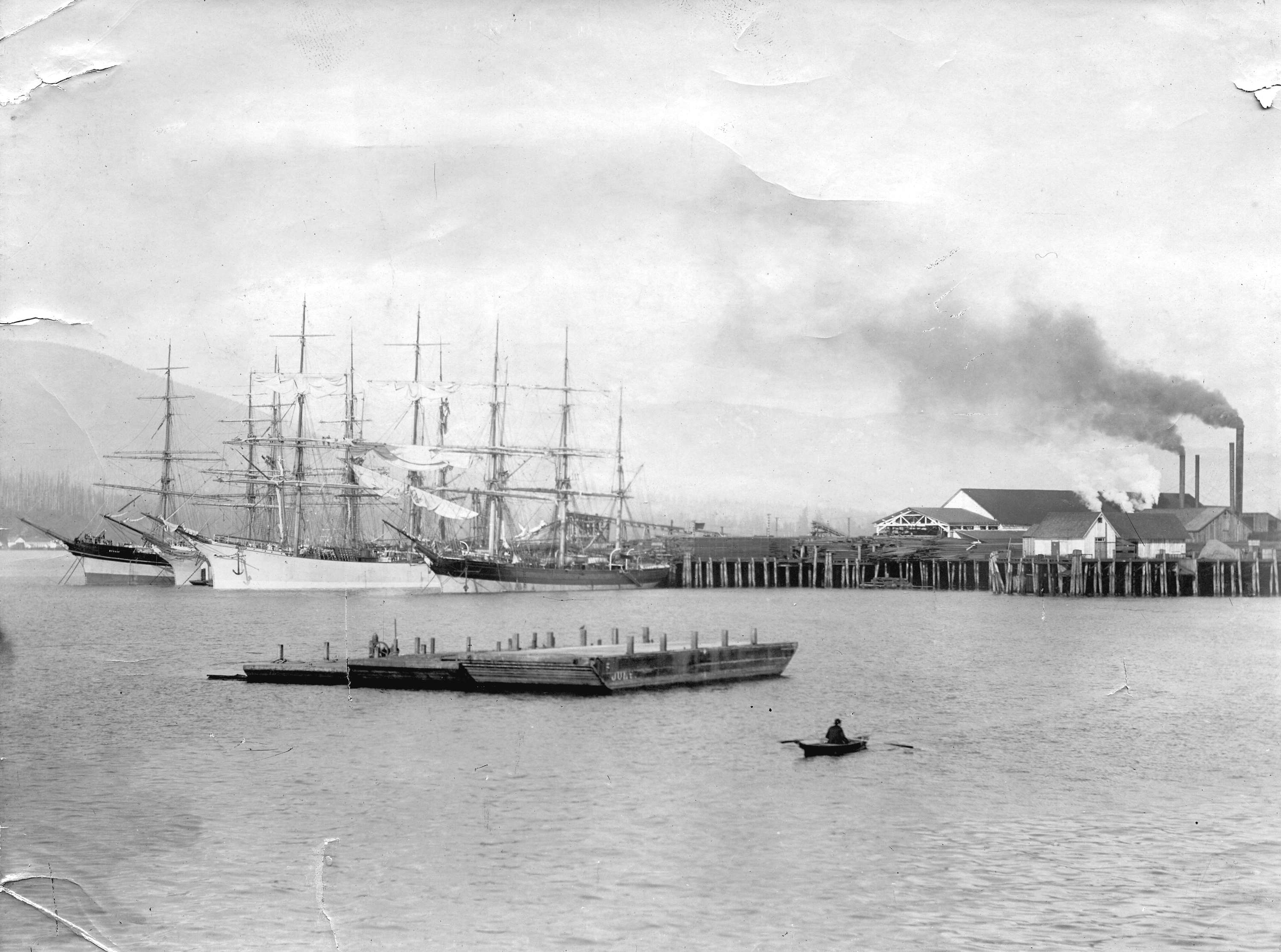

In order to acknowledge where the specimens like our mammoth came from, I used ARCGis (precision map creation software) to map Loomis’s digs with varied precision, depending upon his location descriptions in publications and correspondence.

Overlaying maps of Indigenous nations’ homelands and treaties allowed me to identify the peoples Loomis and fellow paleontologists before and since had exploited.

This map shows where South Dakota, Nebraska and Wyoming meet, with green circles around the locations where Loomis recorded digs. The names of Indigenous nations indicate the recorded names of the nations as different treaties were signed.

But even “non-reservation” land had only been taken barely a generation before: Loomis was digging at Wounded Knee Creek 40 years after the Wounded Knee Massacre of Lakota men, women and children in 1890.

This map zooms in onto the Lakota Pine Ridge Reservation. Wounded Knee Creek was the only identifier Loomis noted for these excavations, so the entire length of the creek is highlighted.

I wanted to provide researchers with this context and to create description that acknowledged the harmful nature of this creator’s work and how exploration and exploitation entwine in fieldwork and research across fields, and to recognize the Indigenous communities affected by his excavations, without ignoring Loomis’s dedicated work as a faculty member and teacher.

Here’s what I wanted to write:

Overly blunt summary can be a satisfying reaction when confronting people’s harmful actions, but this phrasing would not help a researcher wanting to understand Loomis and his papers.

I ended up with this:

Throughout his career, he collected both fossils and Native artifacts for Amherst College collections from the homelands and reservations of Native nations.

—Biographical note, Frederic Brewster Loomis (AC 1896) Papers, 1896-1938 https://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/amherst/ma18.html

Furthermore, one paragraph of the biographical note explicitly situates paleontology’s development within the settler colonial wars against Indigenous peoples of the late 19th century, and its contribution to other forms of resource extraction like mining and oil (and other fossil fuel) extraction.

That paragraph took a lot of revision: was I editorializing? Over-interpreting?

My own judgment was that omitting this background would in fact be contributing to the white supremacist and settler myths of science and individual careers as worth more than human lives and well-being.

The second descriptive tactic I used involved the mapping I described earlier.

June-September 1931

Accompanied by Louis H. Walz (AC 1931) and John W. Harlow.

South Dakota: Porcupine and Wounded Knee Creeks, Pine Ridge Reservation. In Oglala Lakota Nation.

Wyoming: Van Tassell. On Lakota and Arapaho homelands taken by the Act of February 28, 1877.

—Expedition chronology, Frederic Brewster Loomis (AC 1896) Papers, 1896-1938 https://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/amherst/ma18.html

In creating a chronology of his fieldwork, I named the nations where Loomis worked. The repetition over his 20+ documented digs helps underline and reinforce Indigenous presence and sovereignty. This example corresponds to the highlighted site on the second map image.

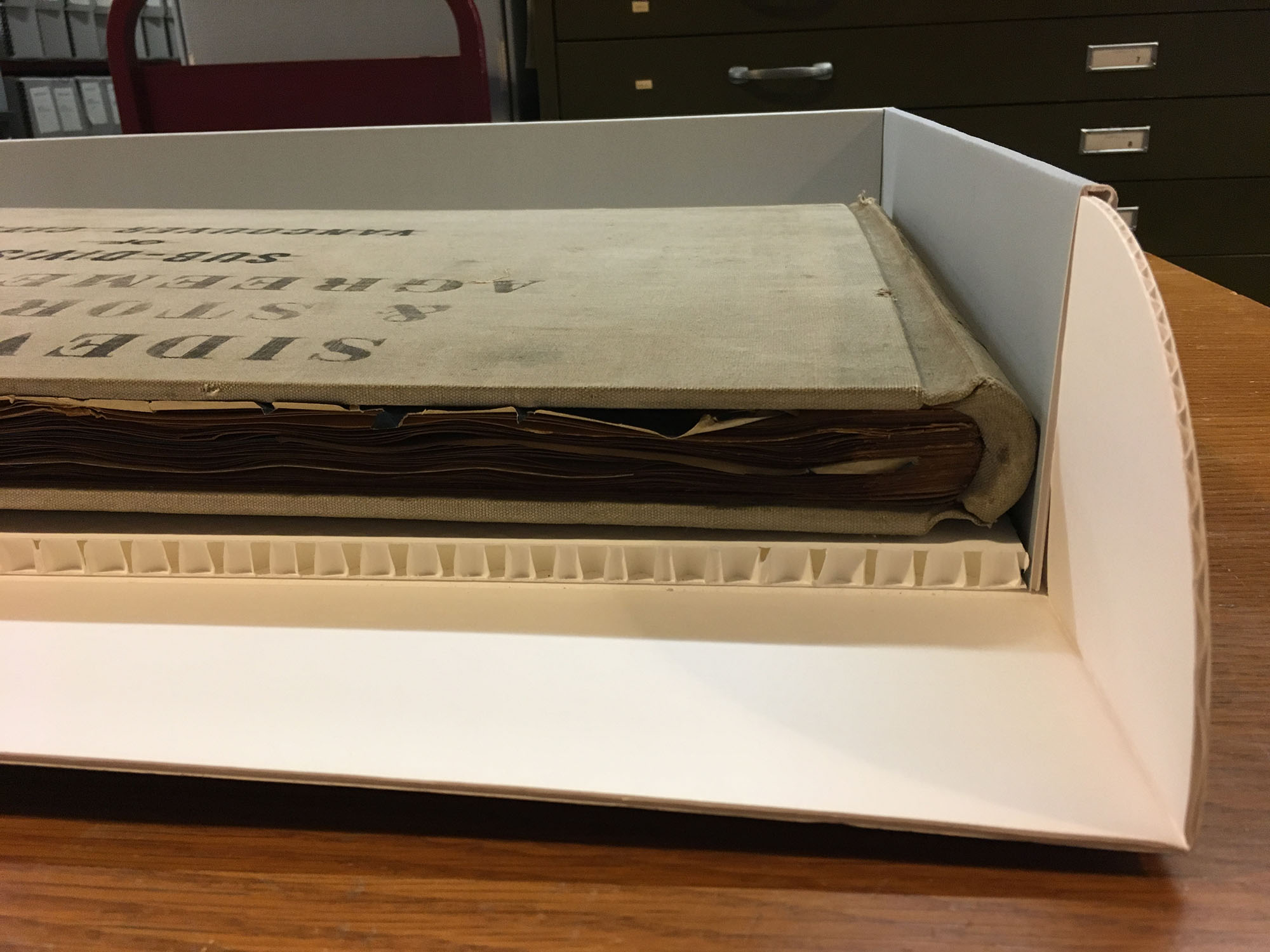

Part of archival work is documenting who and where our collections come from. We keep records about our collections that track how we acquired the materials we hold. In archives, we typically define collections by their source (whether from a person, a family, or an organization like the Office of Admissions). This practice (and related actions like not mixing materials from different origins, even if the documents refer to the same events) reflect a key principle of archival work that we call provenance.

provenance

n. (provenancial, adj.) — 1. The origin or source of something. – 2. Information regarding the origins, custody, and ownership of an item or collection.

Notes: Provenance is a fundamental principle of archives, referring to the individual, family, or organization that created or received the items in a collection. The principle of provenance or the respect des fonds dictates that records of different origins (provenance) be kept separate to preserve their context.

—Society of American Archivists. “Provenance.” Society of American Archivists Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology. https://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/p/provenance.

By acknowledging the true costs of past scientific fieldwork supported by the College, and refusing to continue the myth-making about unused wasteland and White discoverers, I simply extended the same principle to include the subject of the collection, not just the origin of the physical papers.

Archival description expresses professional ethics and values.

—Principle 1, from the Revised Statement of Principles for Describing Archives: A Content Standard (DACS)

New revised principles for our professional standard for describing archival materials are under consideration by the Society for American Archivists.

These new principles begin with the fundamentals of what we do, and why we do it. Description is ethical work. How we describe records’ creators, subjects, and content is and should be a place where we stop enabling Whiteness and its associated myths. Academic disciplines require sources for fuel like any other fire, and for too long, communities, peoples, and lands constructed as “other” have been those sources.

References

- Bradley, Lawrence W. Dinosaurs and Indians: Paleontology Resource Dispossession from Sioux Lands. Denver: Outskirts Press, Inc. 2014.

- Caswell, Michelle. “Teaching to Dismantle White Supremacy in Archives.” The Library Quarterly 87, no. 3 (2017): 222–35.

- Dussias, Allison M. “Science, Sovereignty, and the Sacred Text: Paleontological Resources and Native American Rights.” Maryland Law Review 55, no. 1 (1996): 84–159.

- Redman, Samuel J. Bone rooms: from scientific racism to human prehistory in museums. Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Society of American Archivists Technical Subcommittee on Describing Archives: A Content Standard (TS-DACS). “Revised Preface and Statement of Principles for Describing Archives: A Content Standard.” under consideration, posted Aug 6 2018. https://github.com/saa-ts-dacs/dacs/pull/20.

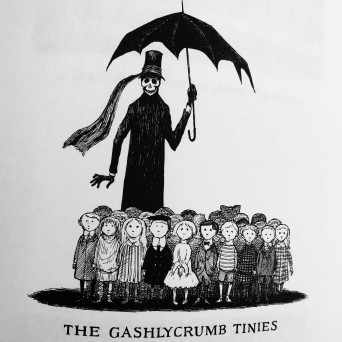

Although the season of ghosts, vampires, and bogeymen has ended, the spirit of the dark and disturbed doesn’t have to. Edward Gorey has a lot of works that we were unable to include in this post—be sure to come visit them in the

Although the season of ghosts, vampires, and bogeymen has ended, the spirit of the dark and disturbed doesn’t have to. Edward Gorey has a lot of works that we were unable to include in this post—be sure to come visit them in the

I initially assumed that the non-human fossils were not an ethical concern, until I remembered SUE. The T. rex fossil at the Field Museum (Chicago, IL) had been purchased at auction for $8 million after protracted court cases were required to determine ownership after the 1990 dig on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation.

I initially assumed that the non-human fossils were not an ethical concern, until I remembered SUE. The T. rex fossil at the Field Museum (Chicago, IL) had been purchased at auction for $8 million after protracted court cases were required to determine ownership after the 1990 dig on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation.