From a photocopy of the original broadcast transcript of WNYC’s Art in New York airing on October 13, 1943. The program aired from 5:45 to 6:00 PM ‘Eastern War Time.’

WNYC – New York’s Own Station, Art in New York Program. H. Stix, Dir.

THE PORTRAIT AND THE MODERN ARTIST

Adolph Gottlieb:

We would like to begin by reading part of a letter that has just come to us:

“The portrait has always been linked in my mind with a picture of a person. I was therefore surprised to see your paintings of mythological characters, with their abstract rendition, in a portrait show, and would therefore be very much interested in your answers to the following—”

Now, the questions that this correspondent asks are so typical and at the same time so crucial that we feel that in answering them we shall not only help a good many people who may be puzzled by our specific work but we shall best make clear our attitude as modern artists concerning the problem of the portrait, which happens to be the subject of today’s talk. We shall therefore, read the four questions and attempt to answer them as adequately as we can in the short time we have. Here they are:

1 Why do you consider these pictures to be portraits? 2 Why do you as modern artists use mythological characters? 3 Are not these pictures really abstract paintings with literary titles? 4 Are you not denying modern art when you put so much emphasis on subject matter?

Now, Mr. Rothko, would you like to tackle the first question? Why do you consider these pictures to be portraits?

Mark Rothko:

The word portrait cannot possibly have the same meaning for us that it had for past generations. The modern artist has, in varying degrees, detached himself from appearance in nature, and therefore, a great many of the old words, which have been retained as nomenclature in art have lost their old meaning. The still life of Braque and the landscapes of Lurcat have no more relationship to the conventional still life and landscape than the double images of Picasso have to the traditional portrait. New Times! New Ideas! New Methods!

Even before the days of the camera there was a definite distinction between portraits which served as historical or family memorials and portraits that were works of art. Rembrandt knew the difference; for, once he insisted upon painting works of art, he lost all his patrons. Sargent, on the other hand, never succeeded in creating either a work of art or in losing a patron—for obvious reasons.

There is, however, a profound reason for the persistence of the word ‘portrait’ because the real essence of the great portraiture of all time is the artist’s eternal interest in the human figure, character and emotions—in short in the human drama. That Rembrandt expressed it by posing a sitter is irrelevant. We do not know the sitter but we are intensely aware of the drama. The Archaic Greeks, on the other hand used as their models the inner visions which they had of their gods. And in our day, our visions are the fulfillment of our own needs.

It must be noted that the great painters of the figure had this in common. Their portraits resemble each other far more than they recall the peculiarities of a particular model. In a sense they have painted one character in all their work. This is equally true of rembrandt, the Greeks or Modigliani, to pick someone closer to our own time. The Romans, on the other hand, whose portraits are facsimiles of appearance never approached art at all. What is indicated here is that the artist’s real model is an ideal which embraces all of human drama rather than the appearance of a particular individual.

Today the artist is no longer constrained by the limitation that all of man’s experience is expressed by his outward appearance. Freed from the need of describing a particular person, the possibilities are endless. The whole of man’s experience becomes his model, and in that sense it can be said that all of art is a portrait of an idea.

Adolph Gottlieb:

That last point cannot be overemphasized. Now, I’ll take the second question and relieve you for a moment. The question reads “Why do you as modern artists use mythological characters?”

I think that anyone who looked carefully at my portrait of Oedipus, or at Mr. Rothko’s Leda will see that this is not mythology out of Bulfinch. The implications here have direct application to life, and if the presentation seems strange, one could without exaggeration make a similar comment on the life of our time.

What seems odd to me, is that our subject matter should be questioned, since there is so much precedent for it. Everyone knows that Grecian myths were frequently used by such diverse painters as Rubens, Titian, Veronese and Velasquez, as well as by Renoir and Picasso more recently.

It may be said that these fabulous tales and fantastic legends are unintelligible and meaningless today, except to an anthropologist or student of myths. By the same token the use of any subject matter which is not perfectly explicit either in past or contemporary art might be considered obscure. Obviously this is not the case since the artistically literate person has no difficulty in grasping the meaning of Chinese, Egyptian, African, Eskimo, Early Christian, Archaic Greek or even pre-historic art, even though he has but a slight acquaintance with the religious or superstitious beliefs of any of these peoples.

The reason for this is simply, that all genuine art forms utilize images that can be readily apprehended by anyone acquainted with the global language of art. That is why we use images that are directly communicable to all who accept art as the language of the spirit, but which appear as private symbols to those who wish to be provided with information or commentary.

And now Mr. Rothko you may take the next question. Are not these pictures really abstract paintings with literary titles?

Mark Rothko:

Neither Mr. Gottlieb’s painting nor mine should be considered abstract paintings. It is not their intention either to create or to emphasize a formal color—space arrangement. They depart from natural representation only to intensify the expression of the subject implied in the title—not to dilute or efface it.

If our titles recall the known myths of antiquity, we have used them again because they are the eternal symbols upon which we must fall back to express basic psychological ideas. They are the symbols of man’s primitive fears and motivations, no matter in which land or what time, changing only in detail but never in substance, be they Greek, Aztec, Icelandic, or Egyptian. And modern psychology finds them persisting still in our dreams, our vernacular, and our art, for all the changes in the outward conditions of life.

Our presentation of these myths, however, must be in our own terms, which are at once more primitive and more modern than the myths themselves—more primitive because we seek the primeval and atavistic roots of the idea rather than their graceful classical version; more modern than the myths themselves because we must redescribe their implications through our own experience. Those who think that the world of today is more gentle and graceful than the primeval and predatory passions from which these myths spring, are either not aware of reality or do not wish to see it in art. The myth holds us, therefore, not through its romantic flavor, not through the remembrance of the beauty of some bygone age, not through the possibilities of fantasy, but because it expresses to us something real and existing in ourselves, as it was to those who first stumbled upon the symbols to give them life.

And now Mr. Gottlieb, will you take the final question? Are you not denying modern art when you put so much emphasis on subject matter?

Adolph Gottlieb:

It is true that modern art has severely limited subject matter in order to exploit the technical aspects of painting. This has been done with great brilliance by a number of painters, but it is generally felt today that this emphasis on the mechanics of picture making has been carried far enough. The Surrealists have asserted their belief in subject matter but to us it is not enough to illustrate dreams.

While modern art got its first impetus thru discovering the forms of primitive art, we feel that its true significance lies not merely in formal arrangements, but in the spiritual meaning underlying all archaic works.

That these demonic and brutal images fascinate us today, is not because they are exotic, nor do they make us nostalgic for a past which seems enchanting because of its remoteness. On the contrary, it is the immediacy of their images that draws us irresistibly to the fancies, the superstitions, the fables of savages and the strange beliefs that were so vividly articulated by primitive man,

If we profess a kinship to the art of primitive men, it is because the feelings they expressed have a particular pertinence today. In times of violence, personal predilections for niceties of color and form seem irrelevant. All primitive expression reveals the constant awareness of powerful forces, the immediate presence of terror and fear, a recognition and acceptance of the brutality of the natural world as well as the eternal insecurity of life.

That these feelings are being experienced by many people throughout the world today is an unfortunate fact, and to us an art that glosses over or evades these feelings, is superficial or meaningless. That is why we insist on subject matter, a subject matter that embraces these feelings and permits them to be expressed.

_________________________________________________________

This edition of Art in New York was hosted by Hugh Stix. Hugh Sylvan Stix owned and managed the non-profit Artists’ Gallery on East 57th Street in Manhattan. After its opening in 1936 the gallery became showcase for emerging artists. Among those were Willem de Kooning, Louis Eilshemus and Louise Nevelson.

Stix’s gallery moved to 113 West 13th Street in 1940. He saw it as a stepping stone for struggling artists to help them to become accepted by more established galleries. The progressive tabloid PM described Stix as having studied art at Harvard but making his living “in the sales department of a grocery concern.” [*] He and his wife Marguerite later became absorbed with sea shells and wrote, The Shell: Five Hundred Million Years of Inspired Design. Stix died in 1992 at the age of 85. In a 1976 interview Stix said that Gottlieb and Rothko had originally proposed the WNYC show episode to him.

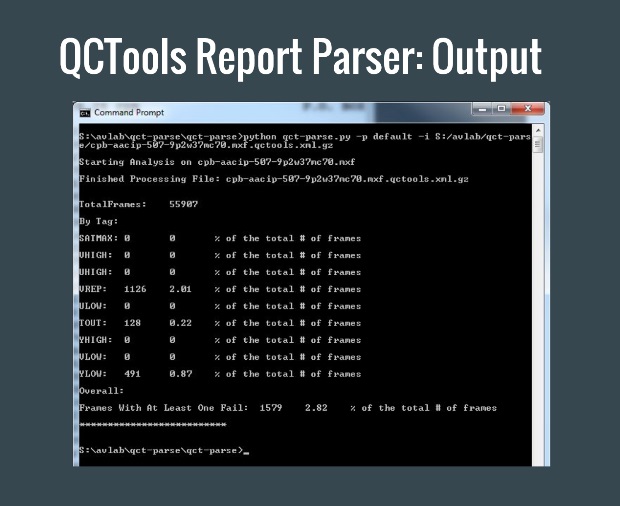

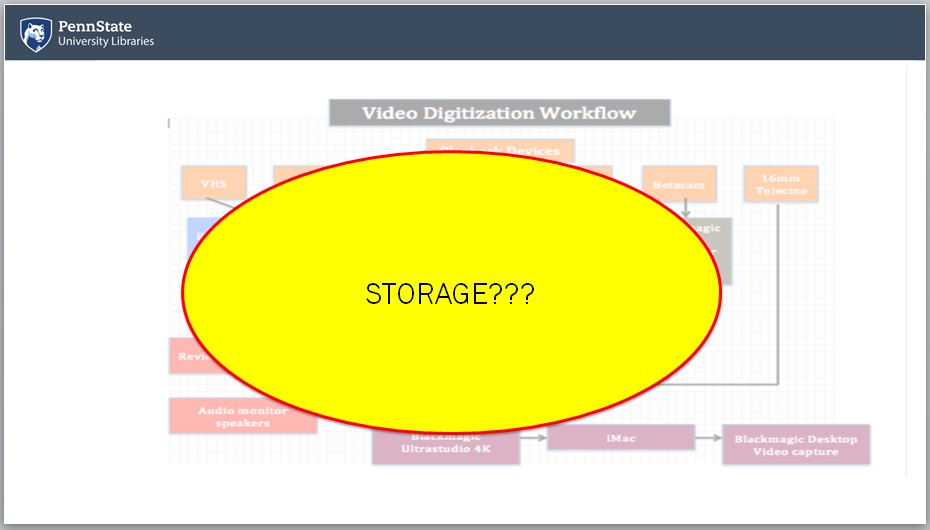

The New York Public Radio Archives gets several requests each year for this broadcast. Sadly, to-date no audio copy of this program has been found anywhere. We suspect, however, that lacquer transcription discs of the broadcast were cut allowing for someone to produce the above transcript. Since this broadcast was made at the height of World War II, these discs were most likely to have been glass-based rather than the conventional aluminum-based lacquers, as vital metals like aluminum were being reserved for the war effort. Subsequently, many World War II era transcription discs have not survived the ravages of time. On the other hand, if you do happen to find this broadcast recording, please let us know!

[*] “PM’s Weekly News of Art,” July 28, 1940. pg. 45.

Opening up the Archive: 50 years of life on campus

Opening up the Archive: 50 years of life on campus

My first project as a graduate assistant involved the Gloria Jahoda Collection – or rather, collections. An author whose husband taught at Florida State University, Gloria Jahoda initially donated a portion of her personal notes and manuscripts to FSU Libraries forty years ago. Some donors might offer more material to the archives after the first gift; this can happen quickly or many years later. These new items are assessed to see if they fit within the scope of the initial donation and, in many cases, added to the same collection. Sometimes, though, this doesn’t happen. When I started working with her manuscripts, Jahoda’s work was spread across seven collections, all donated at different times. I was first tasked with looking over the materials to find a major theme that might unite them into a single collection. I divided the work into new series – like smaller chapters in a single book, series help organize a collection by grouping items together based on their original purpose. I then rearranged the materials, removed duplicate publications, relabeled folders, and copied unstable materials (like old newspaper articles) onto paper that wouldn’t discolor or deteriorate. As this was happening, I learned a lot about who Gloria Jahoda was.

My first project as a graduate assistant involved the Gloria Jahoda Collection – or rather, collections. An author whose husband taught at Florida State University, Gloria Jahoda initially donated a portion of her personal notes and manuscripts to FSU Libraries forty years ago. Some donors might offer more material to the archives after the first gift; this can happen quickly or many years later. These new items are assessed to see if they fit within the scope of the initial donation and, in many cases, added to the same collection. Sometimes, though, this doesn’t happen. When I started working with her manuscripts, Jahoda’s work was spread across seven collections, all donated at different times. I was first tasked with looking over the materials to find a major theme that might unite them into a single collection. I divided the work into new series – like smaller chapters in a single book, series help organize a collection by grouping items together based on their original purpose. I then rearranged the materials, removed duplicate publications, relabeled folders, and copied unstable materials (like old newspaper articles) onto paper that wouldn’t discolor or deteriorate. As this was happening, I learned a lot about who Gloria Jahoda was.