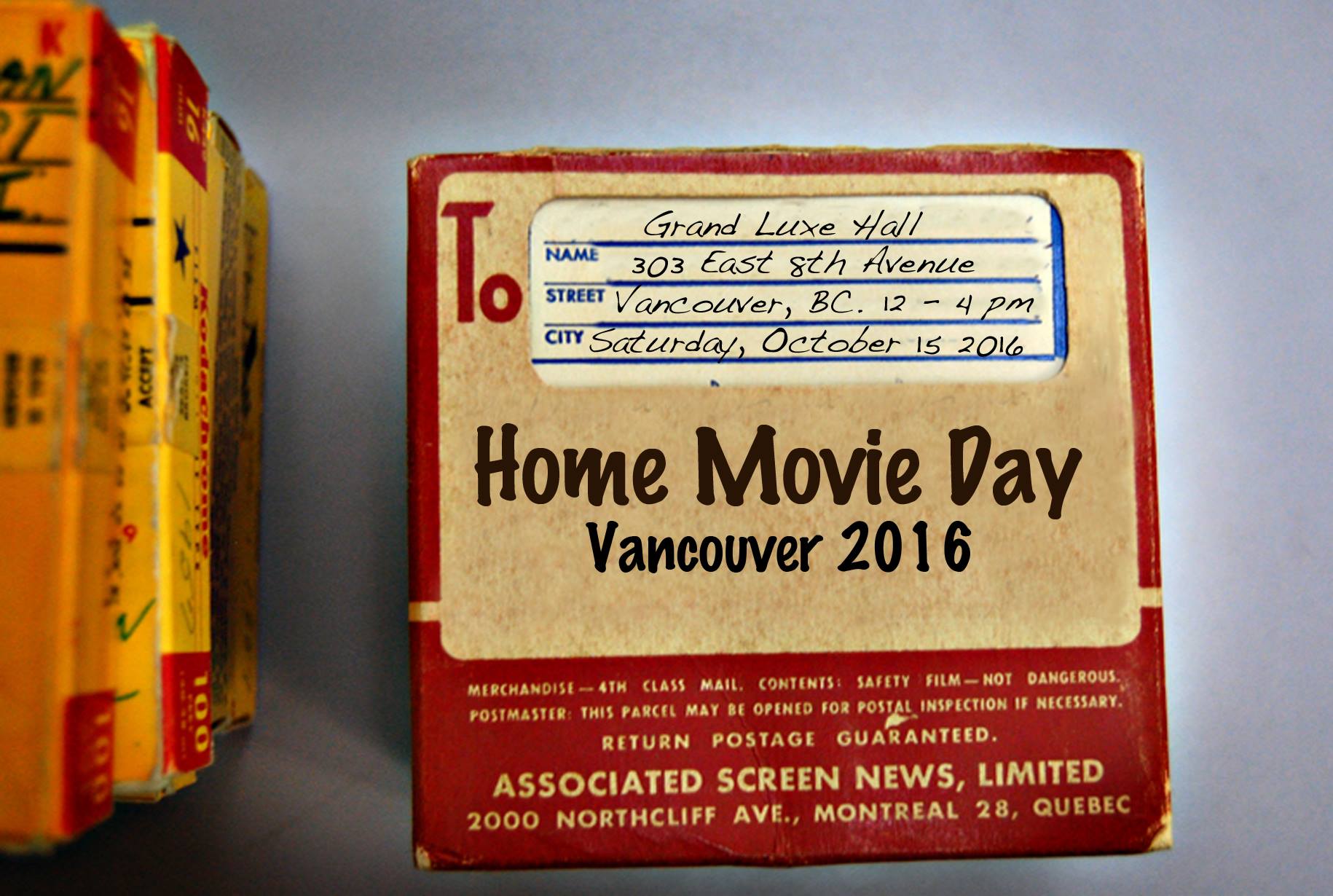

Vancouver: Exponential Change is coming to Vancity Theatre on November 20th and 27th at 3:30 pm. It is the seventh annual screening of digitized movies from the Archives’ holdings. Michael Kluckner, local historian, will be providing insightful commentary, while Wayne Stewart, pianist, will provide music for the film segments shot without sound. This year’s show takes a look at what Vancouverites have gotten up to in their spare time. Here is a preview of this year’s screening.

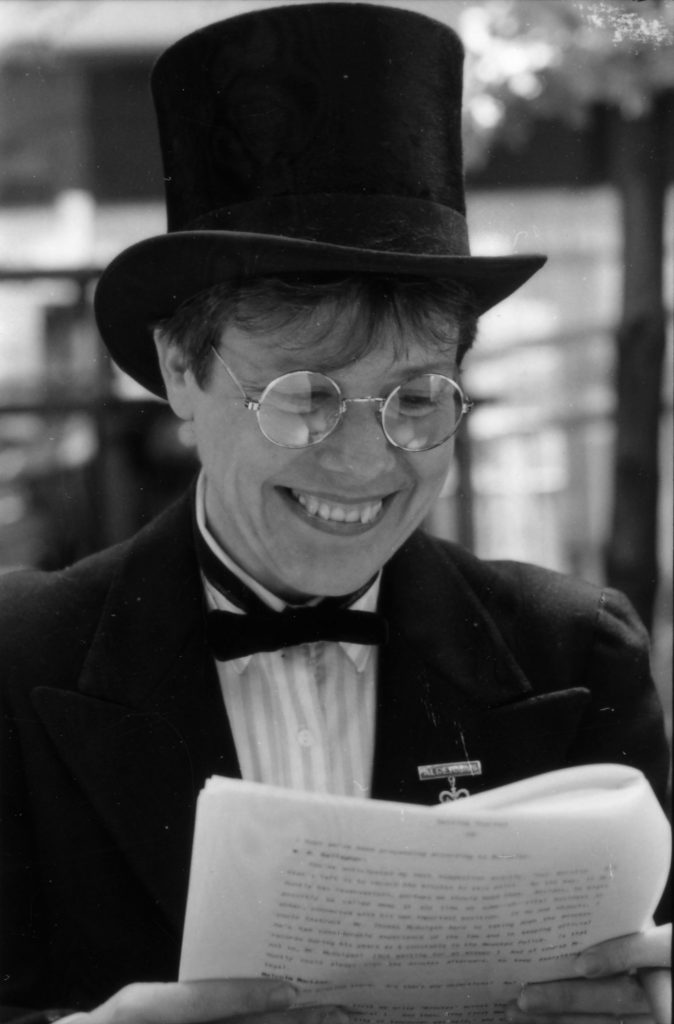

The first film of the series includes excerpts from Bastard Love, a film made by prominent Vancouver families in 1928, including members of the Rogers, Tupper, and Molson families, and shot on the grounds of Shannon Estate. It was a home-made production shot with the characteristic melodrama found in films of that period. The dialogue slides tell bits of the story, with amusing lines, such as, “Can you come with us to Switzerland?” and “How perfectly ripping!”

Still from Bastard Love, 1928. Reference code AM1368-S3-: 2015-049.1

After spending time in the black and white silent era, the program moves onto Vancouver Honeymoon, a coloured tourism promotional, created by the City and the Greater Vancouver Tourism Association, and sponsored by local companies. One will enjoy a drive along the Sea to Sky highway, as it was circa 1960, take a stroll in Stanley Park, check out parts of UBC, and marvel at the natural beauty in which Vancouver is nestled, while being reminded that Vancouver is “so young her story is still being written, but old enough to develop a personality that is all her own.”

Still from Vancouver Honeymoon, 1961. Reference code: AM1487-: 2013-020.24

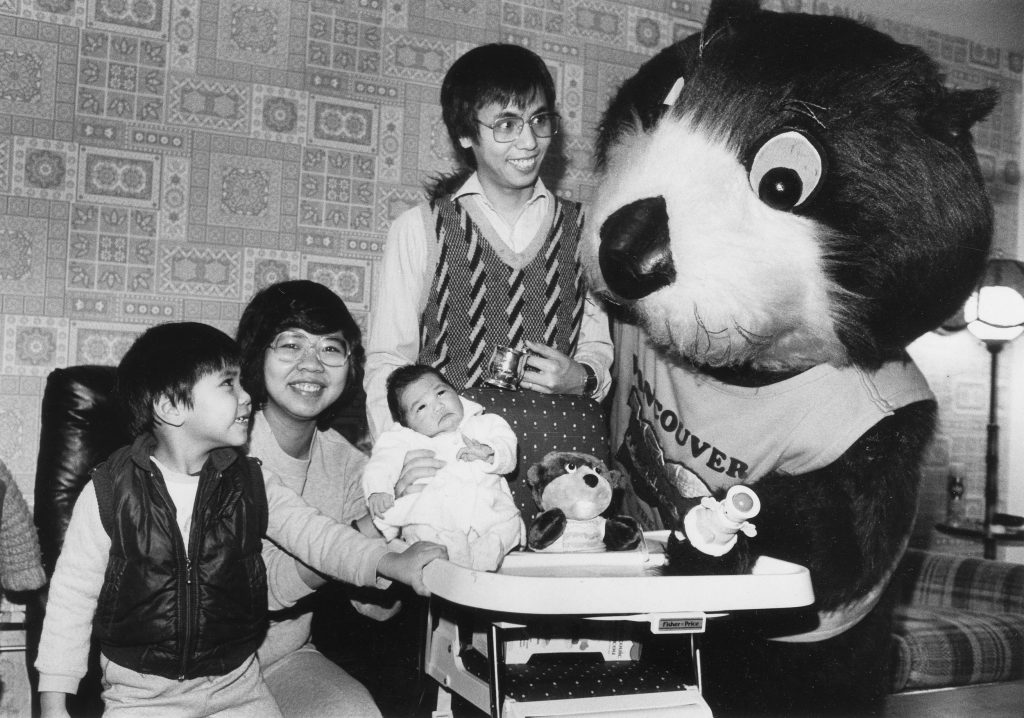

After honeymooning, one will be taken through PNE footage shot around 1950, then jump forward a few decades with various excerpts from Vancouver’s centennial and Expo celebrations from 1986. Great street and aerial footage abounds in these segments, allowing one to see how much Vancouver has, and has not Expo-nentially changed.

Still from PNE Grounds, 1961. Reference code: AM1601-S1-: 2012-010.14

Still from Expo Views, 1986. Reference code: AM1553-8-S7-: MI-239

Regardless of whether it is the 1920’s, 50’s, 60’s, 80’s, or today, it is clear that Vancouverites have been and still are busy enjoying their leisure time creating, playing, relaxing, and exploring the beautiful city many of us call home.

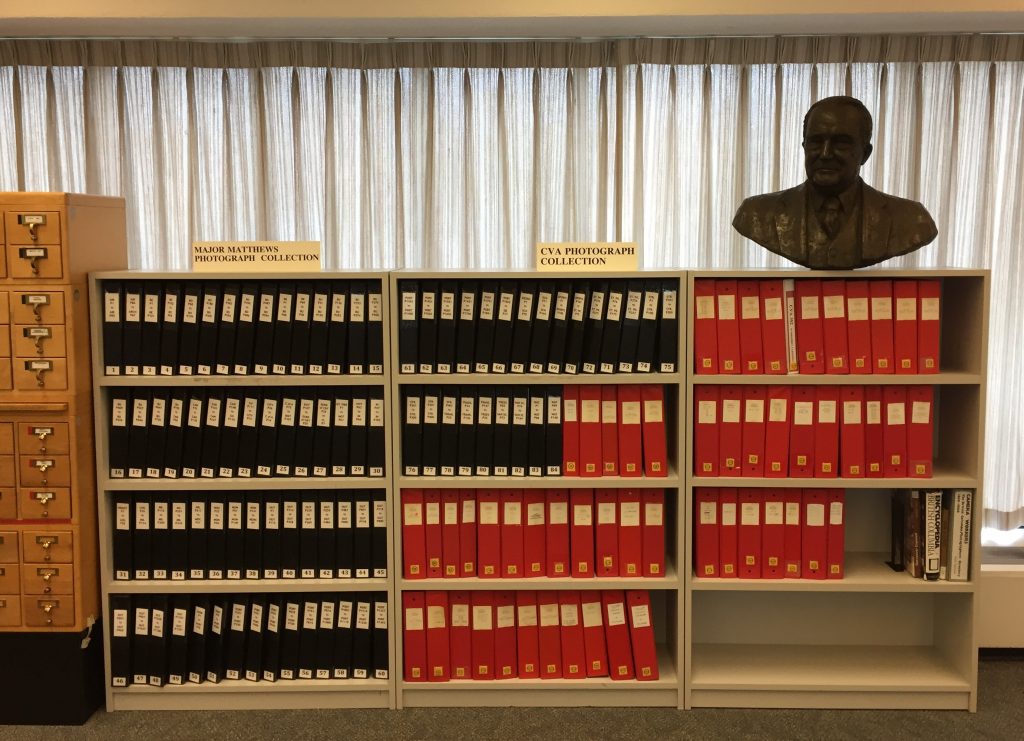

Also in the offerings on November 20th is a rescreening of 2014’s show Vancouver – A Progressive City. This screening includes construction of Lions Gate Bridge, early milk delivery service, and a cameo by Major Matthews, the city’s founding archivist. It looks at Vancouver’s workforce, commerce, heritage, culture and important celebrations. Here is the trailer for the 2014 redux.

Vancouver: Exponential Change screens November 20th and November 27 at 3:30 pm. Vancouver – A Progressive City screens November 20th at 6:45 pm.

![Panoplia omnium illiberalium mechanicarum... / Hartmann Schopper (Frankfurt : Georg Rabe for Sigmund Feyerabend, 1568) [probably rebound in the 1870s]](https://consecratedeminence.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/schopper1568-e1475340565157.jpg?w=300&h=225)