First, an Invocation, borrowing Auden’s own words*: It is impudent of me to trespass at all inside a field where so many great and good people have spent their lifetimes. I can only try to limit the offense by confining my remarks to one aspect of his thought: Time

Auden only occasionally focused his attention directly on time, approaching the subject more often in tangent to other thoughts. But he did approach it in the recording above, harkening back longingly to an earlier era, when the poet held greater sway. I suspect he might begrudge us for pulling him so jarringly into the present, disturbing his high strangeness for our present purpose, but I’ll do it nonetheless:

Wystan Hughes Auden, born 109 years ago, has been following me. He has been for months.

This is, of course, both unlikely and impossible. Unlikely, in that it would be decidedly out of character for him to do so, but more so, in that we hardly share affinities:

He was reborn into Christianity by and in the stirrings of the Second World War, by philosophy, by the loss of his mother, through the slipping love with Chester Kallman, and of course much more – while I have abstained almost entirely from religion, tracking from the aggressive atheism of the young to a respectful agnosticism, while in the main seeking rational explanations for the numinous.

He was a Major Poet, winning, as we hear in the above recording, the 1956 National Book Award for poetry for The Shield of Achilles. A 1948 Pulitzer precedes it, for Age of Anxiety. No slouch. I, on the other hand, am generally uninterested in poetry. I barely read it, in spite of otherwise omnivorous reading habits, and I certainly don’t write it. Moreover, though I like to think I have my moments, my prose is choppy, shallow, and stubborn, rendered like a once tall wave, puttering ashore. His is somehow both more fluid and crisp, smoothing into rich sand across the page.

There are other differences between us, to be sure, mostly trivial. But it’s more than just unlikely that I would be a figure of fascination for him. It’s impossible: Auden, the so good, so great, so dead author of some of the finest poetry of the last century, shuffled off this mortal coil in 1973, in Vienna, Austria. I was born years later, and half a world away; we quite simply could not have crossed paths. But we cannot reduce these suits to a man, nor can we easily account for the connections we forge. For the now seven months since my wife and I moved to New York City from Austin, Texas, he has been a close companion.

So I will rephrase. Auden has preceded me in time, true. But I have preceded him in space, and my awareness of his past presence has followed, almost to a rule, in a fitting echoic neighborly decency, by anywhere from hours to days:

From dining at St. Mark’s and 3rd (“valuable property” he tells us in the recording above), only to learn days later I was mere feet from his home – to our offices at WNYC, where he first emerged coiled upon the core of a quarter inch reel on my third day on the job; and again months later, a few days after we received a new shipment from the New York City Municipal Archives, astride a pair of waxy acidic 16” transcription discs for me to transfer and archive; and then later still in praise of the namesake of our archives’ catalog, Constantine Cavafy – to the basement of McNally Jackson, pursuing another author’s intriguing plug for Kierkegaard after an anxious two-day wait, to see Auden’s name staring back surprised on the book’s spine aside Either/Or and Fear and Trembling – and from there, still summoned unbidden, across pages on St. Mark’s, about Shakespeare, and by Lewis Carroll, and, eventually, learning about Kierkegaard and unlearning Arendt.

When Julie and I grabbed our first cab from La Guardia to South Slope, I’m pretty sure we rolled over his February House, since razed by Robert Moses to make way for the BQE. Just today (February 21), I discovered the sly bit of reconnaissance Auden took of my adopted home of St. Louis, winning a late-in-life literary award from SLU. And again just today (February 21), as sat down to commit finally to beginning this appreciation, I learned it is his birthday.

In a way, it’s not surprising that he should take advantage of his strange power and so frequently skip days and hours and even years: the dramatic mystery is that we should always so unanimously agree upon exactly how many hours and days and years to skip. Years, then hours and days, nearly every time.

Our connection is trivial, of course, and increasingly less serendipitous, as I’ve increasingly sought his work out, but it doesn’t feel trivial. And it doesn’t feel chosen. It feels like kismet. It feels meaningful. Actually, no, not meaningful. This: It makes me more prone to appreciate what is meaningful in what he left behind. And it makes me wonder what he would have made of all this odd flitting about time.

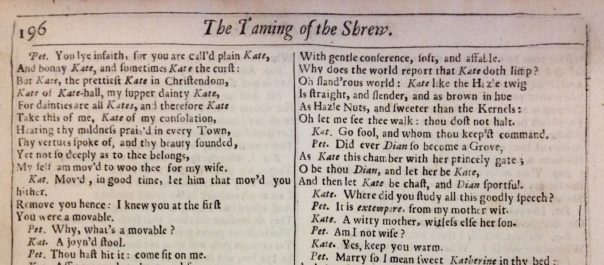

Auden taught at Swarthmore from 1942 to 1945, during which time he composed The Sea and the Mirror, an “ars poetica” in which he enlists characters from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, speaking directly to the audience after a performance, to provide a poetic exploration of his thoughts on art and poetry. It is brilliant, deliciously high-concept, fascinating in premise and execution… and utterly beyond our scope.

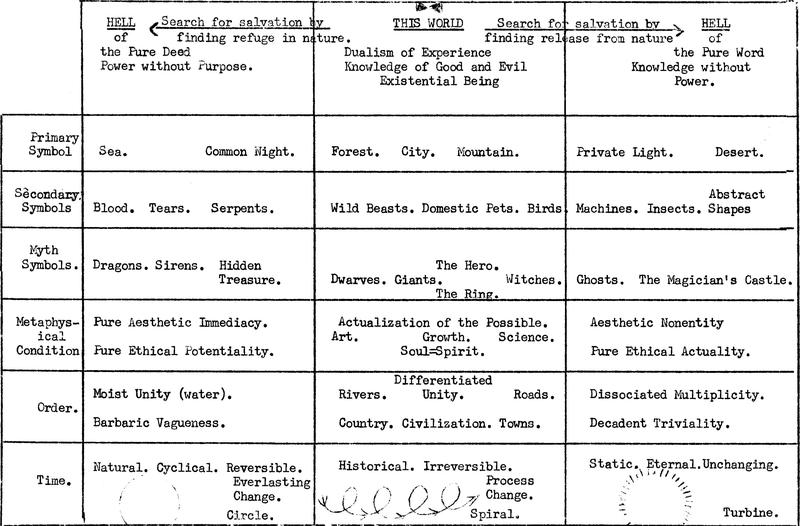

But during his time at Swarthmore he also left behind a chart (a portion of which is pictured below), used in his seminar “Romanticism from Rousseau to Hitler,” meant to dispel our instinctive Manichean leanings, in poetry and life. Here is an easier inroads.

On either side are the Hells of Pure Deed (seeking refuge in nature) and Pure Word (seeking release from it) and at the center, This World. Through this triptych he wound the themes of sin, sex, politics, and myth… symbols, theories, and disease… And time.

In the Hell of Pure Deed, time is a circle; the Hell of Pure Word, a turbine. In This World it was (and is) a spiral. Untangling the meaning behind Auden’s spiral metaphor is tricky without a clearer context, but perhaps we can be seen as crossing paths there, as separate stories mingling in the spiral’s memorial churn. Or, alternatively, time on either side of hell remains an eternal round now. But time in This World isn’t quite a spiral; time is a wave, sinuform and regular. Auden at the crest, the apogee, me in its undertow, the base, swimming with the currents of an insistent pressing time – never quite meeting (how could we?), but mirrored nonetheless.

Were I forced to pick a point when our paths might more properly intersect, in real time, where we are not split by those hours and days and years, I would probably join the fellow irresponsibles and sit in on his Swarthmore class. This is perhaps due in part to the fact that this predates the earliest audio available of Auden in the WNYC Archives by a good 3 to 6 years – in anyone’s life a good stretch, in a life like Auden’s, an eternity.

That earliest-Auden-audio is from a 1948 episode New York University’s Reader’s Almanac, captured originally on transcription disc at the WNYC studios, later reformatted to compact disc in 2007, and transferred into our digital repository just this year. On it, we get to hear him in the role of the critic, discussing the role of evil in Charles Williams’ All Hallow’s Eve with Richard McLaughlin and Warren Bauer. It begins in media res, with Auden telling us that a person’s attitude to life must emerge in the work they write – a promising place to start if we’re in search of Auden’s own attitudes towards his work, his life, and time. Still, as insightful as this brief recording is, I prefer a more direct address, and the above is sadly incomplete and the audio suffers from an assertive and distracting crackle.

1956, National Book Awards

Virgilia Peterson, conferring upon Auden the National Book Award for poetry for The Shield of Achilles, tells us that “he stands symbol for the treasure that the old world has in our times bestowed upon the new.” This is true these times too.

Acceptance speeches at awards ceremonies are a strange genre – somehow simultaneously pandering and sincere, a place of cloying superficiality and naked emotion, and a platform for thanks and gratitude, but also for the persistent and egregious misuse of the word “humble.” At their best, though, they can be home to elegant statements of grand ideas (sometimes political, hopefully not) and serve as summations of the best of human hopes achieved.

The best summation for Auden would have been a recitation of The Shield of Achilles, of course, which he wisely eschewed, lest he face the National Book Council’s no-doubt exquisite play-off music. No, Auden’s speech that day instead dealt with the place of the poet – in society, and in time. For Auden, the poet was the only kind of person to want to have existed in an earlier age, one that he describes as briefly and eloquently as allowed in his allotted time – one where the poet held a richer social and spiritual presence, one where a poet could have read his sacred work aloud at such a solemn and meaningful occasion. But one can’t help but feel he is dissembling a bit.

Since we are so focused on time, we should note that in a quick slip into rhetorical symmetry, he pinpoints that very much earlier age at 1956 BC, an age in which the sacred was a public experience shared by all, and in which real men spoke in verse. There is no doubt that the numinous permeated a wider swath of human experience in the actual societies of 1956 BC, but wouldn’t the poet’s envied eye more likely focus on what Auden had earlier in his career considered “the first and last time in history [that] an art, drama, became the dominant religious expression of a whole people, [with] the [poet] the most important figure in their spiritual life,” i.e. the golden age of Greek theater? Is it fair to guess that the fudged the dates by more than a millennium, or that this is likely what he had in mind? I suspect so, though it’s probably not fair to judge him for it.

But this is quibble, a minor complaint, even if we’d rather he didn’t play it so fast and loose with time. Perhaps we should forgive that falsely symmetrical flourish. We should worry, though, about the wider view.

We all spin little stories so that we might weave our lives in them. Auden is no different. But the tale he tells of time at the National Book Awards is partial. To fill it out, we must look to Auden’s interpretation of Kierkegaard.

Kierkegaard looked to mankind and saw three attitudes to life – The Aesthetic, The Ethical, and The Religious. If these seem vaguely familiar, I encourage you to peruse again Auden’s chart, here, or above. I’d also note that Auden mentions the distinction between The Aesthetic and The Ethical enough times in his prose anthology, The Dyer’s Hand, that I quickly lost count.

Auden, in his 1952 edited edition of The Living Thoughts of Kierkegaard, had the wisdom to set these to a historical narrative of the development of religion, enriching what was a narrative of individual personal development, granting them a societal breadth and historical depth missing (to me) in what I’ve read of Kierkegaard’s work, by the simple act ordering them in historical time.

His narrative, while brief, is still too long to repost here. I encourage you to seek it out. I’ll reiterate my agnosticism here. I paraphrase:

The Aesthetic (e.g. The Greek Gods)

Humanity began with a sense of the self struggling in opposition to an overwhelmingly powerful “not-self.” The Greek Gods came to solve this by taking over the role of the passions – human emotions belonged to the Gods. In fact, emotions were the Gods. Art was the performance of rituals meant to draw in the sacred. Strength was virtue, weakness was sin. Humans themselves were blameless, but their experience of the sacred lacked acknowledgement of the sense of choice they knew was part of their conscious lives. On the basis of that, the lack of accounting for good and evil, and the failure to deal with anxieties concerning death, this theology failed.

The Ethical (e.g. Greek Philosophy)

To resolve these anxieties, Greek philosophers began to search for something that transcended death – universal truths, science, ideas. These ideas became the divine. Knowledge was virtue, ignorance was sin, but art existed merely to coax the unenlightened into belief and the deification of ideas could not rationally account for the will to pursue those ideas. On this account the religion of ideas failed.

The Religious

Humanity sought something more permanent in its place. Humanity sought that permanence in the fulfillment of the Ethical in revealed religion, in a relationship with God that could not be severed. In both Greek theologies the relationship with the divine was intermittent – either Gods chose to enter an individual, or the individual sought to pursue the divine. The Gods of the Aesthetic – feelings – and the God(s) of Ethical – ideas – became in the new religion the ideas and feelings of individual human beings. In the new theology, evil was the rebellion against this more permanent relationship. This is the first theology that accounts for the feeling of choice, but in order to to retain that choice, God became a distant figure.

To consider this little narrative historically true would be generous, but that’s hardly the point. Its purpose is to provide a place to house belief, to provide a religion, a philosophy, a code of behavior, call it what you will, [without which one] cannot live at all. In this, I think, it succeeds, even while I disagree with it. It succeeds because it is narrative, because it enlists the forces of time to its purpose. It forces one to consider one’s place in it, and one’s movement through it.

The Auden of the National Book Award address, flirting as it does with the Romantic idea of sacred (read: artistic) possession, seems to live in the Aesthetic age. Much as I loath to admit it, I probably would be classed in the Ethical, Aesthetic in fits. Auden the man, arguably all three, but ultimately, the Religious.

Oddly though, we don’t get a sense for the place of art in the “religious” life. Oddly too, that in order that we are left a God to commune with, God must not only remain an utter mystery – lest faith lapse into certainty, and our autonomy vanish as well – but also that each person must forge their own connection to that God. So perhaps he isn’t dissembling in his acceptance speech when he bemoans the loss of shared sacred experiences. In the Aesthetic-Ethical-Religious arc, we really do see a shift to individualist relation to God. The numinous can’t be shared, at least not easily, even through art.

The Sea and the Mirror ends in what Auden would call The Reconciliation of Art and Life in the Religious, with poor players making atonal, near-noise, frantic failed music, before approaching first the void of nonexistence and ultimately the sounded note [of] the restored relation, a musicoserio expression of the bridging of the gulf between God, art, and life, enlisting the metaphor of puissant pure sound.

In one of his Dyer’s Hand essays, “Notes on Music and Opera,” Auden wonders What is music about? What does it imitate? Answering that it imitates Our experience of Time in its twofold aspect, natural or organic repetition, and historical novelty created by choice. I’d argue this sells both Time and Music short. Perhaps this is again unfair – the essay was really more of a mash of notes than a reasoned critique, but still, both Time and Music are richer concepts than he allows. Time and music are more than repetition and novelty; they are narrative and memory too.

He may be thinking of measured metre or poetic pulse, a formal appreciation of poetic structure grew throughout his long career. Or perhaps he’s thinking, existentialist that he was, of the eternal present of which we are only ever aware. But the second a second-hand clicks to the next, isn’t it lost to memory already? Memory will forever win every battle, every Pyrrhic victory, but will forever submit to the whims of the present. In The Sea and the Mirror, Auden’s Caliban mocks his demiauthor’s felicitous claim to put a mirror up to nature, arguing that, in a mirror, art and nature provide a mutual reversal of value. This is worth reflecting on, but the phrase is perhaps truer of Time: Time, History, Memory, put a mirror up to Now. And it is Art that finally reconciles Memory with the Present.

In one of his final American interviews, which likely aired on WNYC in 1972, Auden would speak with Douglas Cooper about the meaning of art. Auden answers to Cooper’s earnest questions on the role of art in life verge on the nihilistic, at least they did to my ears, three days into a new career in a new town. Asked whether people act differently as a result of poetry, Auden provides what by now was something of a pat answer about the role of not just poetry, but all arts: 1) Paraphrasing Samuel Johnson: The sole aim of writing is to enable readers a little better to enjoy life, or a little better to endure it; and 2) from Auden himself, The arts are our chief means of breaking bread with the dead.

Breaking bread with the dead is an pithy expression of the significance of time, but is spoken with its distant wit drained by repetition, dried into aphorism. Bread isn’t manna, ambrosia, or milk-and-honeyed cake; there is no transubstantiation; The dead remain dead. Still, it is worth reflecting upon. The Cooper tape was one of the first things I’d done on the job, and one of my first genuine encounters with his work. It took a while, though, before I came to consider the phrase. And it finally occurred to me that it cuts both ways.

*Any language taken or derived from Auden is in italics.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

Readers Almanac – WNYC archives id: 5837; Municipal archives id: LT 6790, LT5396

National Book Award – WNYC archives id: 150222; Municipal archives id: LT7121

Additional audio from the Douglas Cooper Distinguished Contemporaries Collection – WNYC archives id: 92067

Everyone enters a field of work for one reason or another. For me, pursuing a Masters of Library and Information Studies began from a desire to be an archivist, a type of information professional that is largely underrated, misunderstood, or even unheard of by the public. The mystery regarding the profession drew me in initially. Popular culture depicts archives as dark and secluded repositories with strict access restrictions guarded by a gatekeeper, hesitant to divulge any of the archives’ secrets. Think of the less-than-helpful associate in the Jedi Archives who turns Obi-Wan away in Star Wars Episode II; she might as well have shushed him while she was at it!

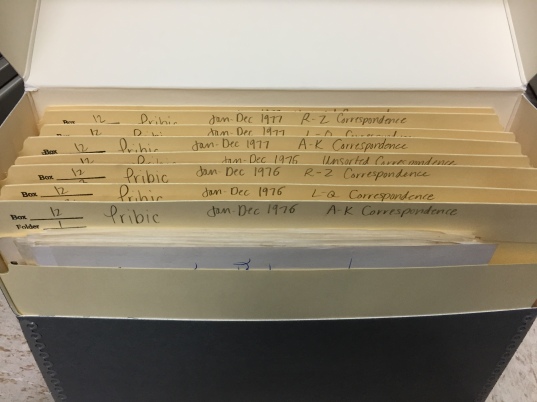

Everyone enters a field of work for one reason or another. For me, pursuing a Masters of Library and Information Studies began from a desire to be an archivist, a type of information professional that is largely underrated, misunderstood, or even unheard of by the public. The mystery regarding the profession drew me in initially. Popular culture depicts archives as dark and secluded repositories with strict access restrictions guarded by a gatekeeper, hesitant to divulge any of the archives’ secrets. Think of the less-than-helpful associate in the Jedi Archives who turns Obi-Wan away in Star Wars Episode II; she might as well have shushed him while she was at it! In a job where creating order out of disorder is a top priority, the profession tends to attract many an OCD history buff. There’s something viscerally satisfying about organizing a dusty old mess of papers into a neat collection of documents in acid-free folders, legibly labeled for ready accessibility.

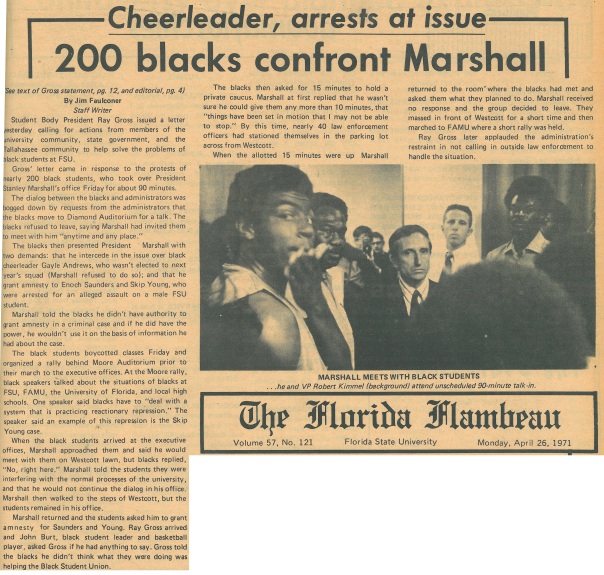

In a job where creating order out of disorder is a top priority, the profession tends to attract many an OCD history buff. There’s something viscerally satisfying about organizing a dusty old mess of papers into a neat collection of documents in acid-free folders, legibly labeled for ready accessibility. Many steps go into creating this order, however. After gaining legal custody of the documents, the archivist has to “gain intellectual control,” which is a sophisticated way of saying “learn exactly what kind of stuff is in the collection.” In order to do this, one must comb through the contents, which could take a very long time depending on how many linear feet the collection is, and create an inventory. The collection I’ve been “gaining intellectual control” of is called the Douglas and Jeannette Windham Papers, which contains the papers and publications of Douglas and Jeannette Windham, a distinguished FSU alumni couple. I’ve listed the materials that are in the collection, including personal papers, correspondence, academic articles, photographs, and professional reports. Once intellectual control is established, I can work with the archivist to determine a plan for order and begin to folder the contents into acid-free folders. A.K.A. the fun part! The kind of fun that is on par with labeling the shelves of your pantry, or color-coding your closet. (Yes, this is how I live).

Many steps go into creating this order, however. After gaining legal custody of the documents, the archivist has to “gain intellectual control,” which is a sophisticated way of saying “learn exactly what kind of stuff is in the collection.” In order to do this, one must comb through the contents, which could take a very long time depending on how many linear feet the collection is, and create an inventory. The collection I’ve been “gaining intellectual control” of is called the Douglas and Jeannette Windham Papers, which contains the papers and publications of Douglas and Jeannette Windham, a distinguished FSU alumni couple. I’ve listed the materials that are in the collection, including personal papers, correspondence, academic articles, photographs, and professional reports. Once intellectual control is established, I can work with the archivist to determine a plan for order and begin to folder the contents into acid-free folders. A.K.A. the fun part! The kind of fun that is on par with labeling the shelves of your pantry, or color-coding your closet. (Yes, this is how I live).