Folklorist and librarian Elaine Lambert Lewis O’Beirne-Ranelagh (1914-1996) began producing programs for WNYC in 1943. At that time, before her marriage, she was known professionally as Elaine Lambert Lewis, assistant in charge of radio work for the Brooklyn Public Library. She also started and oversaw the organization’s folklore collection.

Lewis majored in Greek and the classics at Vassar College and took a real shine to mythology. That interest led to graduate studies in folklore at the University of Indiana under renowned folklorist Stith Thompson. In 1935 she was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship to study Italian fairy tales in Rome. Upon returning to New York, Lewis landed at the Brooklyn Public Library, where she started the folklore collection.

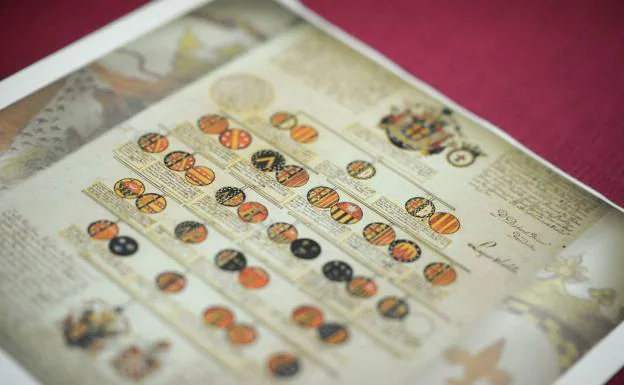

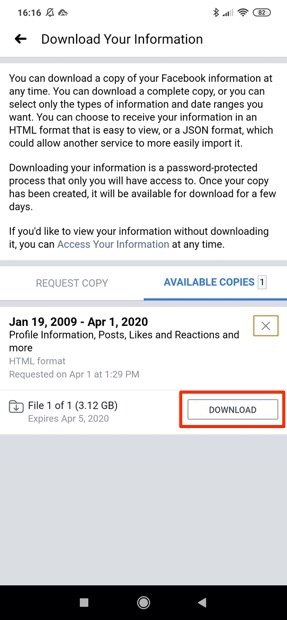

Librarian Milton James Ferguson (1879 –1954) circa 1912.

(Wikimedia Commons)

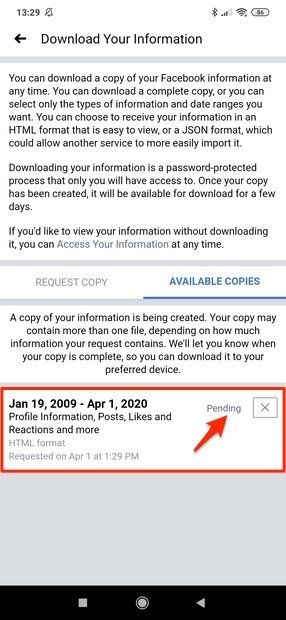

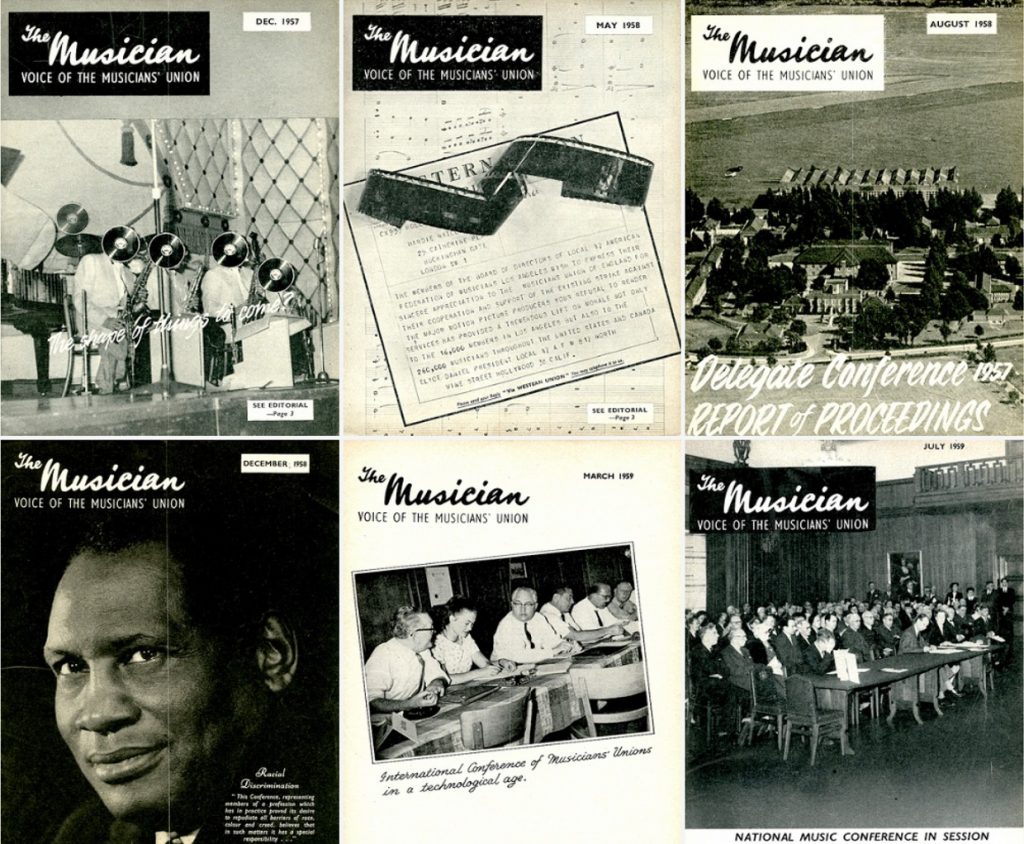

Folk Songs For the Seven Million premiered on July 13, 1943. In announcing the program, the BPL’s Chief Librarian Dr. Milton James Ferguson called it a new effort in the field of democratic education. “It springs out of the conviction that city people need to know what they have in common with one another and how closely their traditions fit into the pattern of national tradition.”[1] After less than a year on the air, the show was considered “the best cultural program” by Ohio State University’s Institute for Education by Radio.

The weekly series provided carefully researched programs full of stories, traditions and customs, all placed in their context. It was the perfect show for New York, the city of immigrants, as it surveyed the rich ‘old world’ traditions and influences found here in rhyme, ballad, and song. The show was also keen to highlight the importance of African-American and Native American influences, as well as the nation’s earliest settlers from England, Ireland, France, and Mexico. Among the program’s many guests were folklorists Ben Botkin, George Korson, Frank Warner, Louis C. Jones, and Harold W. Thompson and folk singers Tom Glazer, Richard Dyer Bennett, Susan Reed, Lucy and Joan Allison, Jerry Buckley, Dorothy Vander, Josef Marias, George Herzog, Mari Sandoz, Edith Allaire, Tom Scott, and Huddie Ledbetter, a.k.a. Lead Belly.

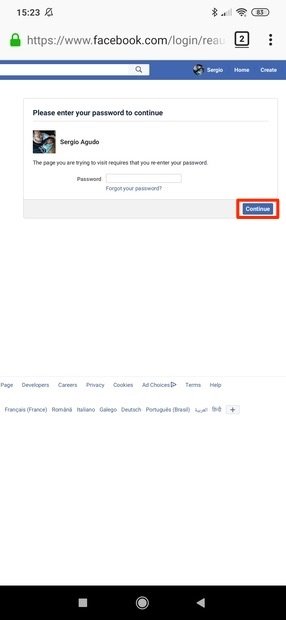

Huddie Ledbetter (Leadbelly) and his wife Martha Promise Ledbetter, in Wilton, Connecticut, February, 1935.

(Alan Lomax Collection/Library of Congress)

Leadbelly in particular was no newcomer to WNYC’s airwaves, having performed for host Ralph Berton at the WNYC American Music Festival, and been a guest on Art Hodes’ Metropolitan Review, as well as having had his own program, Folksongs of America (1940-1941). But the folksinger also had a close personal relationship with Lewis: she was the person he called for help when his wife Martha became ill and was ignored at Bellevue Hospital. Outraged, Lewis readily came to the balladeer’s aid, forcefully asking staffers if they had any idea who this sick woman was. She described Leadbelly as a great musician, and warned, “Do you want it known that this man’s wife died of neglect in your care?”[2]

Folk Songs for the Seven Million also served as outreach for Lewis’ research, allowing her to appeal to listeners for contributions to her collection of thousands of folk songs, lore, and customs. A 1946 Brooklyn Eagle profile said she had received a song from a 90-year-old man who had been taught the tune as a boy by his 85-year-old grandfather. The reporter quoted Lewis as saying, “The supply is endless.”[3] Elsewhere Lewis wrote:

Retired shipmasters have mailed in bushranger ballads; emigrant small-towners, now living in New York, have written down the customs of their childhood; native New Yorkers have come in person to tell of the games and rhymes of their youth, and of local feuds and gangsters; Irish people have provided rich links with American history in recalling the originals of many of our ballads and songs…Much of the material collected is presented on the air, the songs by way of the contributor himself or by a homemade recording of his singing.[4]

Toward the end of World War II, Lewis started collaborating with one of her contributors, James O’Beirne, an engineer and veteran of the 1916 rising. O’Beirne was known as a man with a “good repertoire of Irish songs”[5], and he joined her on the show. They wed the following year and are heard in this November 15, 1946 broadcast titled, “Early European Influence on American Folk Music.”

It appears that Lewis did most, if not all, of the program recordings herself on the family disc cutter.[6] The show at the top of this article on railroad songs was broadcast on March 9, 1944 and a recording, unfortunately incomplete, was located in the Municipal Archives WNYC Collection. The original lacquer discs of the program with O’Beirne immediately above are located with Lewis’ papers at University College Dublin.

Lewis produced two other Brooklyn Public Library programs for WNYC. Library Time, airing October 1944-May 1945, was a fifteen-minute program broadcast twice a month highlighting the various facilities and services provided by the BPL. Lewis also hosted Poets Are People from December 1944 to March 1945. The fifteen-minute Tuesday evening poetry program’s guest list featured the bards Langston Hughes, Oliver St. John Gogarty, William Rose Benet, Padraic Colum, Alfred Kreymborg, and Marianne Moore. Moore, when asked on the January 30 program what she dislikes most in contemporary American poetry, is said to have replied, “I detest our tendency to glorify American virility.”[7] Sadly, we’ve not yet discovered any recordings of Poets Are People.

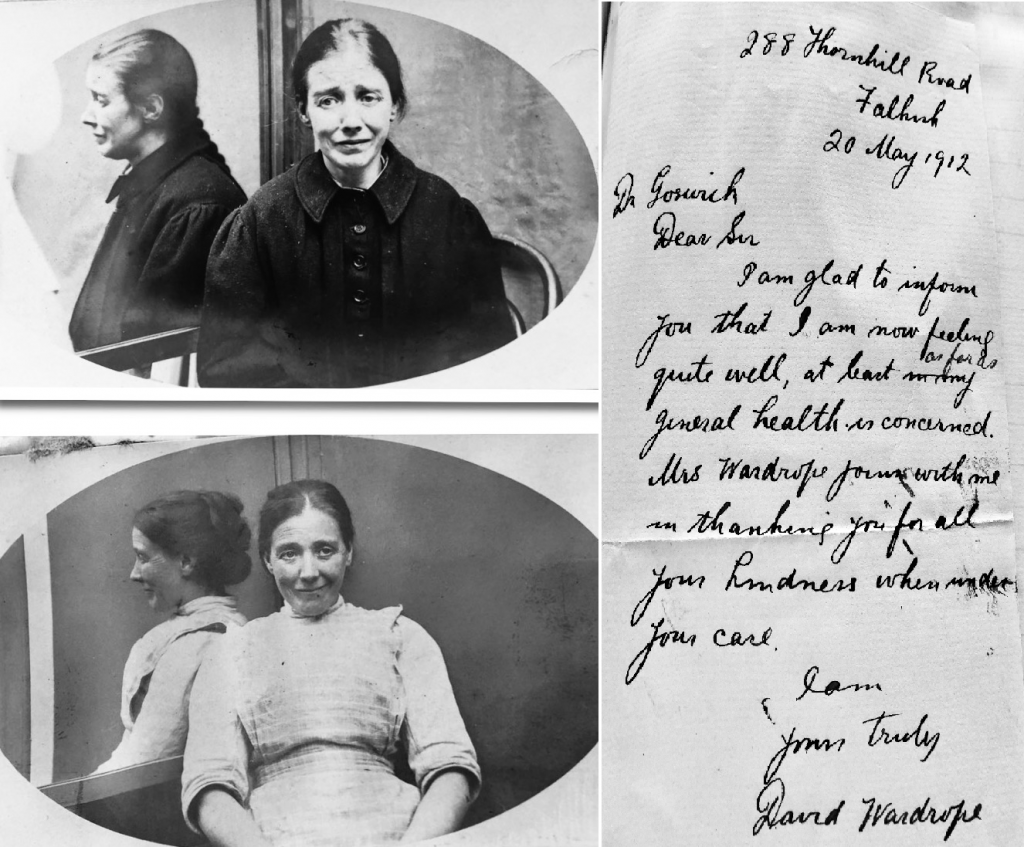

From the February 1945 New York Folklore Quarterly

(WNYC Archive Collections)

But Lewis’ heart was in folk music and folklore. In 1945-1946 she wrote a series of 36 folklore broadcasts for the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) called “The American Scene.” The series was intended for national distribution, but it is not clear if the programs were ever produced. In 1947 she was awarded a second Guggenheim fellowship to complete two books. One was a volume of New York City folk songs, and a survey of Irish folk songs. Her WNYC program Folk Songs for the Seven Million continued to air into 1947.

Lewis and O’Beirne moved permanently from Brooklyn to Ireland in 1953 and changed the family name from O’Beirne to O’Beirne-Ranelagh. The couple had four children, and she continued her folklore research and writing while appearing on some broadcasts for Radio Éireann. She later moved to Cambridge, England, where she worked as the Educational Director of the University of Maryland’s European extension.[8]

Elaine Lambert Lewis O’Beirne-Ranelagh’s tenure at WNYC was significant on two pioneering counts. In the areas of folklore and folk music, she more than picked up where ethnomusicologist Henrietta Yurchenco (Leadbelly’s original producer), left off in 1941; and, as a wartime and postwar broadcaster, she was among a small group of women in a field dominated by men. Both of these achievements have some reflection in her work. Years later, writing as E. L. Ranelagh, she authored two books: The Past We Share: The Near Eastern Ancestry of Western Folk Literature (1979) and Men on Women (1986), a study of male hostility and stereotypes toward women from five thousand years of literature. But it is the conclusion of Lewis’ second Guggenheim application that perhaps gives her the best parting words.

Folklore is my pleasure. I’m afraid that even if it did not illustrate the unity of man, I should be equally devoted. But since it does, collecting and writing in folklore means sharing with and joining with my neighbor. [9]

_________________________________

[1] “Boro Library on First Radio Program Tonight,” The Brooklyn Citizen, July 13, 1943, pg.2.

[2] O’Beirne-Ranelagh, Bawn, email correspondence.

[3] Mara, Margaret, “Collector of Folk Songs Finds Higher Interest in Xmas Carols,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 23, 1946, pg.11.

[4] Lewis, Elaine Lambert, “Folk Songs For the Seven Million,” New York Folklore Quarterly, February 1945, pgs. 57-59. Lewis was one of the organizers of the New York Folklore Society and served as its first vice president as well as a contributing editor for its quarterly for which she wrote City Billet: Folklore News and Notes for New York City, a regular column in the quarterly reviewing books, records, and concerts of folklore interest. She also contributed to Library Journal, New York History and The Journal of American Folklore.

[5] McMahon, Deidre, “Ranelagh, Elaine Lambert Lewis O’Beirne-,” Dictionary Irish Biography, https://dib.cambridge.org/viewReadPage.do?articleId=a7581

[6] Juengst, William, “Radio,” The Brooklyn Eagle, February 14, 1945, pg. 8.

[7] Schultz, Robin R., The Web of Friendship: Marianne Moore and Wallace Stevens, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1995, pg. 162.

[8] McMahon, ibid.

[9] Lewis, Elaine Lambert, “Application to the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation,” 1946.

The audio at the top of this article is courtesy of The New York City Municipal Archives.

Special thanks to the National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin.