Daguerreotype of Charles Thompson by Chandler Seaver, Jr., of Boston, ca 1855

Charles Thompson, custodian at Amherst College for more than 40 years in the second half of the 19th century – do you know him? Have you seen photographs of him before, perhaps in an old Olio yearbook? For over 40 years Amherst students graduated and left town with a photograph of Charles Thompson in their copies of the yearbook. Thompson was deeply connected with the College, and with the students’ experience of it, and there is no doubt that those who knew him remembered him fondly.

Most of what we know about Thompson’s life comes from a volume written to raise money for Thompson’s old age by President William Augustus Stearns’ daughter Abigail Eloise Lee. I’ve looked at the book many times over the years, both for the purpose of learning about Thompson’s life and to find details about the College and town during those days. Recently I looked at it again and this time I happened to focus on a passage in which Lee mentions Thompson’s experiences as a sailor. I’d never noticed this information enough to wonder about it, but this time I did.

People who spoke with or heard about Thompson might have known about his years at sea. Apparently he told stories about his adventures, first to the Stearns children, and then to people in Amherst. In the years since his death, though, we’ve probably associated Thompson primarily with his work for the Stearns family and later for the College, while those years on a ship have been unexplored and would probably have been lost to history if it weren’t for Lee’s book.

Lee quotes from a manuscript of her father’s to describe Thompson’s career as a sailor:

and

Pres. William A. Stearns (ca. 1858), Thompson’s friend and employer.

In other words – and this is what interests me – by the time Charles Thompson followed the Stearns family to Amherst in the late 1850s he had seen far more of the world than had the great majority of the people who knew him, or thought they did. It’s interesting to think about his experiences and what he learned as he traveled the seas in comparison to what the average citizen of Amherst – town or college – experienced or learned. Were there times when someone said something to him that made him recall what he’d witnessed and done, and what they would never know?

I wanted to know more about Thompson’s history, so I turned to resources at my fingertips.

Lee had said that Stearns found a position for Thompson with a “Captain Charles Evans,” a mariner Stearns knew personally, and that his first trip was on a whaler, an experience he remembered vividly:

Investigations in the newspaper database and at the National Maritime Digital Library‘s “American Offshore Whaling Voyages: a Database” led me to conclude that Thompson sailed with Charles Thomas Evans on his ship the Warren. It’s certain that Charles Thomas Evans (not Charles A. Evans, another mariner) was Thompson’s employer: the dates, the ship names, and the details of his death match the clues. What’s more, genealogical websites showed Evans was the husband of Stearns’ sister-in-law Lucy Drew Frazar. She was Evans’ second wife, and the fact that the Stearns family knew her well explains how Thompson came to sail with Evans.

Lee writes that Thompson served as the steward on the Warren, which means that he served Evans in particular, along with other duties:

“The steward was the captain’s personal servant. He kept the captain’s and mates’ cabins in order and waited on the captain and mates at mealtimes in the main cabin. He was in charge of the cook and responsible for keeping track of the stocks of food and other supplies aboard the ship. He was sometimes assisted by a cabin boy. He lived in steerage and his lay [his pay percentage] ranged between 1/60 and 1/150.” (From the site:

Girl on a Whaleship)

From the ship’s deck, Thompson would have witnessed scenes like this one, later prompting memories like the one quoted above:

Currier and Ives, “Whale Fishery,” via the Library of Congress.

Newspapers allow us to follow some of the Warren’s route between 1847 and 1851. This evidence suggests that Thompson boarded the Warren in November 1847 while it was in Warren, Rhode Island, its home port. From there, it went on a 41-month journey (click on first image to start slide show):

To make the point succinctly, Thompson’s voyages looked something like this:

When the Warren returned from its long voyage, Evans seems to have decided he’d had enough of wrangling angry 45-ton mammals. After about 9 months at home, he turned to merchant shipping and became the master of the Kremlin, a boat designed by his brother-in-law Amherst Alden Frazar. According to Lee, Charles Thompson went on two voyages with Evans on the Kremlin. They left New York in late February, 1852 for San Francisco and were reported sighted along South America on March 31.

Kremlin at latitude 6.14 S, longitude 31.40 W on March 31. (Daily Atlas newspaper, May 20, 1852.)

Meanwhile, the Warren was still sailing the seas. Thompson was lucky not to be on it anymore: it burned on July 10, 1852.

On July 26, the Kremlin was nearing San Francisco when the crew sighted a ship in distress:

After providing assistance (no doubt with Thompson’s help as steward), the Kremlin sailed on toward San Francisco, arriving there on August 2. The brig Rostrand limped in behind it.

The Kremlin and the Rostrand arrive in San Francisco (Daily Alta California, Volume 3, Number 214, 3 August 1852.)

Less than two months later Captain Evans died of “ship fever,” a ghastly way to go that involves infectious body lice. Lee’s book says that Charles Thompson tended Evans in his last illness and brought a lock of his hair home to Lucy Evans.

It took almost four months for the news to reach Evans’ family.

“We are well. You have doubtless heard of Uncle Henry’s death. Capt. Charles Evans died at sea of ship fever, Sept. last. The news has just arrived. He was, you know, Lucy Frazar’s husband.” William A. Stearns to brother Jonathan Stearns, 1853 Jan 17.

The Kremlin went on to Shanghai under the first mate, according to Thompson, and departed for London on October 23, 1852. A newspaper report in a column titled “Via Quarantine”(perhaps for more cases of ship fever) shows it in London in the spring of 1853; June newspaper accounts have it arriving in Boston on June 8 or 9, 1853. This was the end of Thompson’s life as a sailor.

Charles Thompson at the College well, ca. 1860.

Altogether, then, Thompson was at sea for a total of about 4 ½ years, beginning with a whaling voyage of 41 months (late November 1847 to sometime in May, 1851) through two additional voyages from early 1852, through his return to New England in June, 1853. He remained in the Boston area for a few years and then moved to Amherst to be with the Stearns family. Amherst must’ve seemed very quiet after his life at sea, and perhaps he preferred it that way.

**********************************************

While researching Charles Thompson’s history, I came across many fascinating sites about the history of whaling. In addition to those mentioned in the text above, here is a selection of great resources:

The New Bedford Whaling Museum , including many additional links under the tab “Digital Scholarship.”

The Whaling Museum of the Nantucket Historical Association, including pages about the whaler Essex, and the 2015 movie about it, “In the Heart of the Sea”

Mystic Seaport, with links to online materials.

The Smithsonian, with a page on whaling, including a section on African American sailors: “On the Water”

The Northeast Document Conservation Center’s project to conserve a logbook: “Starboard Boat Struck a Whale.”

Maritime Heritage Project, a “free research tool for those seeking history of passengers, ships, captains, merchants and merchandise sailing into California during the mid-to-late 1800s.”

Detailed article: Spatial and Seasonal Distribution of American Whaling and Whales in the Age of Sail. Smith TD, Reeves RR, Josephson EA, Lund JN (2012) PLoS ONE 7(4): e34905. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034905

A blog not to be missed: Data narratives and structural histories: Melville, Maury, and American whaling

When I applied to the Special Collections & Archives graduate assistantship, I had one thing in mind: rare books. As an undergrad at FSU, I frequently visited Special Collections for class projects and assignments related to medieval manuscripts and early printed books, knowing that someday I wanted to work with rare material like these. So naturally when I received the news that I was selected for the assistantship, my first thought was of all the rare books I would get to “work with.”

When I applied to the Special Collections & Archives graduate assistantship, I had one thing in mind: rare books. As an undergrad at FSU, I frequently visited Special Collections for class projects and assignments related to medieval manuscripts and early printed books, knowing that someday I wanted to work with rare material like these. So naturally when I received the news that I was selected for the assistantship, my first thought was of all the rare books I would get to “work with.”

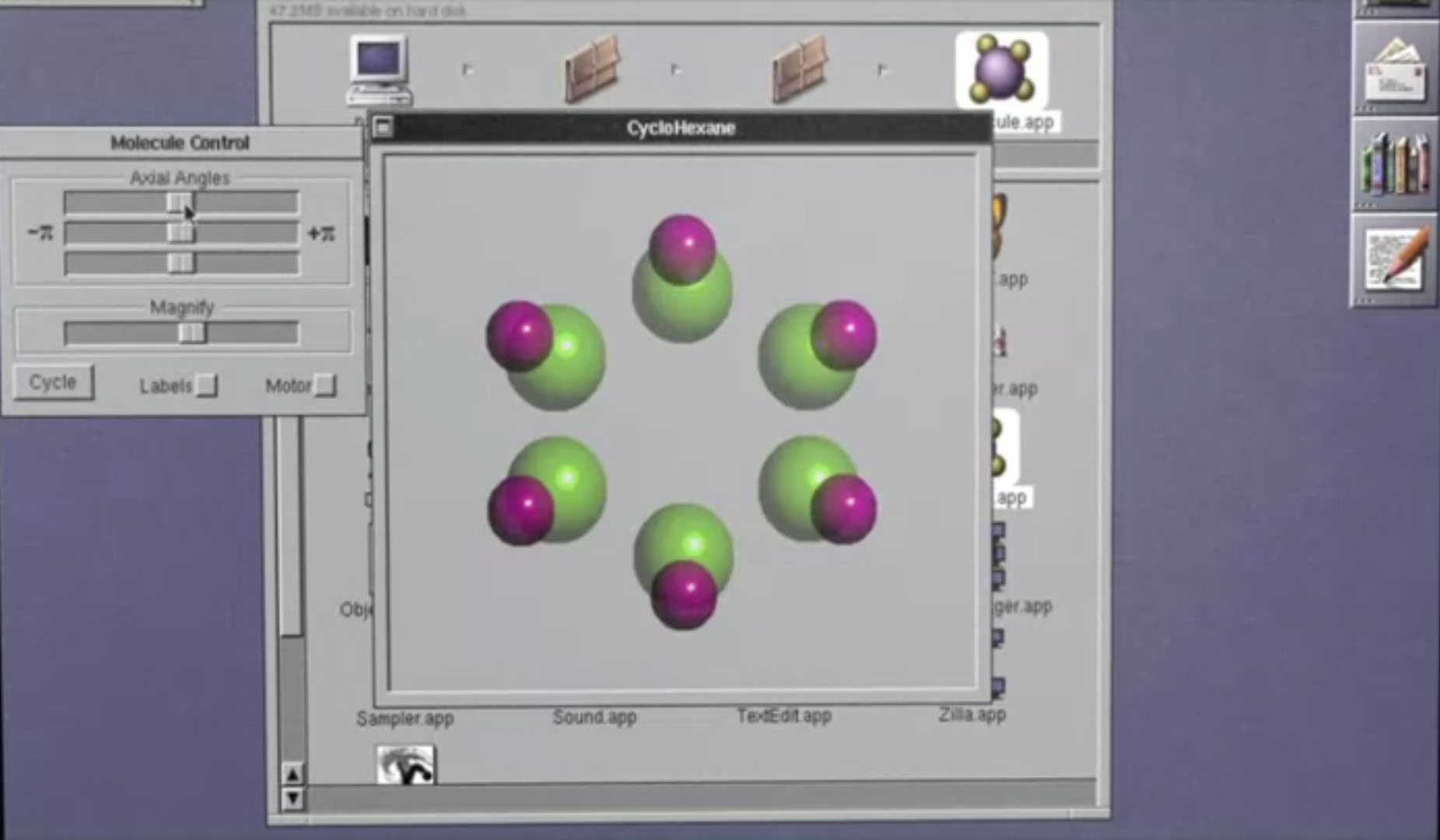

![MediaConch in action. Screenshot from presentation given by Ashley Blewer, Dave Rice and Erwin Verbruggen.]](http://www.vancouverarchives.ca/wp-content/uploads/MediaConch.jpg)