Roethke and Bellow headline 1965 National Book Awards…even though one of them is dead. Ted Roethke’s widow accepts the award for her late husband’s collection The Far Field, and his friend, fellow poet Stanley Kunitz, converts the usual speech of thanks into a eulogy. Noting that Roethke was so talented “he could afford to praise,” Kunitz reveals that among his papers were “twelve hundred poems by other poets written out in his hand. He said he didn’t know what was in a poem until he had transcribed it.” He goes on to describe the various sections of The Far Field, reciting some passages, including one that eerily presages the poet’s death. (Roethke suffered a heart attack while swimming.) He ends by using Roethke’s own description of their craft, praising him “in this matter of making noise that rhymes.”

In the field of History and Biography, the winner is The Life of Lenin by Henry Fischer. Fischer laments how Lenin has become a “mummified idol” of the Revolution and tells how he tried to humanize the man. At the end of his speech, he contrasts Lenin with Gandhi (another biographical subject) and then veers into current events by calling Martin Luther King “the Gandhi of America.”

The winner for Science, Philosophy, and Religion is Norbert Weiner for God & Golem, Inc. He too, sadly, has died and so is eulogized by Dr. Jerome Wiesner (a future president of MIT), who struggles to summarize his colleague’s argument. A founder, indeed coiner of the term, cybernetics (the scientific study of how people, animals, and machines control and communicate information), towards the end of his life Weiner was increasingly concerned about the relationship between Man and machines. His final, perhaps wanly optimistic conclusion, as expressed here, is, “since God cannot be threatened by his creation (Man), Man cannot be threatened by the machine.”

The award for Arts and Letters goes to Eleanor Clark for her book The Oysters of Locmariaquer, part memoir, part investigation of the oystering industry in France’s Brittany region. Clark adds an appreciated note of levity to the proceedings, reading from a “review” of the book written by her ten-year-old daughter. When she does get around to addressing this ostensibly more prestigious honor she hopes it “may help get this book of mine off the Food and Cooking shelves.” She then makes a plea for a new area of bookstores, the Scavengers Shelf, for books of personal inquiry such and hers and, if one gazes into the future, John McPhee, in relation to whom she now appears a natural precursor.

The award for Fiction goes to Saul Bellow for Herzog. Tellingly, Bellow promises that as “the clean-up man” he won’t take up much of their time. (In fact he is the fifth, not the fourth speaker, but clearly, sees himself as the prized slugger of this literary team.) He then launches into a coruscating attack on today’s “rebellious writers,” noting that “polymorphous sexuality and vehement declarations of alienation are not going to produce great works of art.” Isolating one’s self from Society so as to keep one’s hands clean leaves Literature “enfeebled.” In the end, “there is nothing left for us novelists to do but think.” He urges writers to engage with the political, social, and business world. If today’s artist regards his fashionable alienation is significant, “…he is wrong. It is 90 percent cant.”

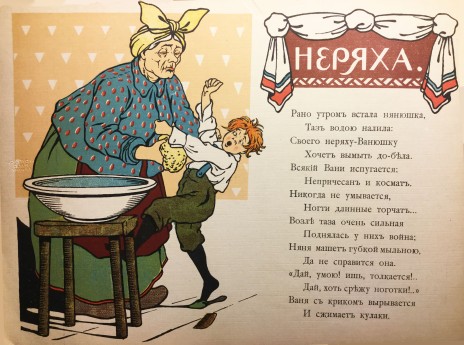

Theodore Roethke (1908–1963) was perhaps the most extreme of the poets who broke out of the Eliot-Auden mode to create a uniquely American poetry harkening back to Whitman. The Poetry Foundation website recounts his unusual upbringing, which provided much material for his poems:

Born in Saginaw, Michigan, his father was a German immigrant who owned and ran a 25-acre greenhouse. He attended the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where he adopted a tough, bear-like image (weighing over 225 pounds) and even developed a fascination with gangsters. His difficult childhood, his bouts with manic depression, and his ceaseless search for truth through his poetry writing led to a difficult life, but also helped to produce a remarkable body of work that would influence future generations of American poets to pursue the mysteries of one’s inner self.

After a long apprenticeship, Roethke finally achieved recognition with his “greenhouse poems” which struck an ominous, ecstatic, deeply mystical note. Adam Kirsch, writing in the New Yorker, claims:

Nearly a century and a half after Wordsworth, Roethke manages to invent an entirely new kind of nature poetry, in which the earth is not reassuringly earthy but teeming and alien. At times, Roethke’s greenhouse even becomes surreally menacing: “So many devouring infants! / Soft luminescent fingers, / Lips neither dead nor alive, / Loose ghostly mouths / Breathing.”

Saul Bellow (1915-2005) was the preeminent American novelist of his day. In addition to three National Book Awards and a Pulitzer Prize, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976. Bellow’s dismissal of “alienation” and “polymorphous sexuality” are part of the gruff yet academically informed heartland sensibility he liked to cultivate. The New York Times, in its obituary, points out that:

The center of his fictional universe was Chicago, where he grew up and spent most of his life, and which he made into the first city of American letters. Many of his works are set there, and almost all of them have a Midwestern earthiness and brashness. Like their creator, Mr. Bellow’s heroes were all head and all body both. They tended to be dreamers, questers or bookish intellectuals, but they lived in a lovingly depicted world of cranks, con men, fast-talking salesmen and wheeler-dealers.

Bellow’s battle against the what he saw as the snide East Coast intelligentsia on one side and the morally incoherent anti-intellectualism of “rebellious” writers on the other, clearly struck a chord with the reading public. He is that rare combination: a serious literary artist who also garnered serious sales. About this, as about so much else, he was unapologetic. Questioned by the Paris Review, he stated:

I don’t like to agree with the going view that if you write a bestseller it’s because you betrayed an important principle or sold your soul. I know that sophisticated opinion believes this. And although I don’t take much stock in sophisticated opinion, I have examined my conscience. I’ve tried to find out whether I had unwittingly done wrong. But I haven’t yet discovered the sin.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

WNYC archives id: 150023Municipal archives id: T1081-T1082

![]()