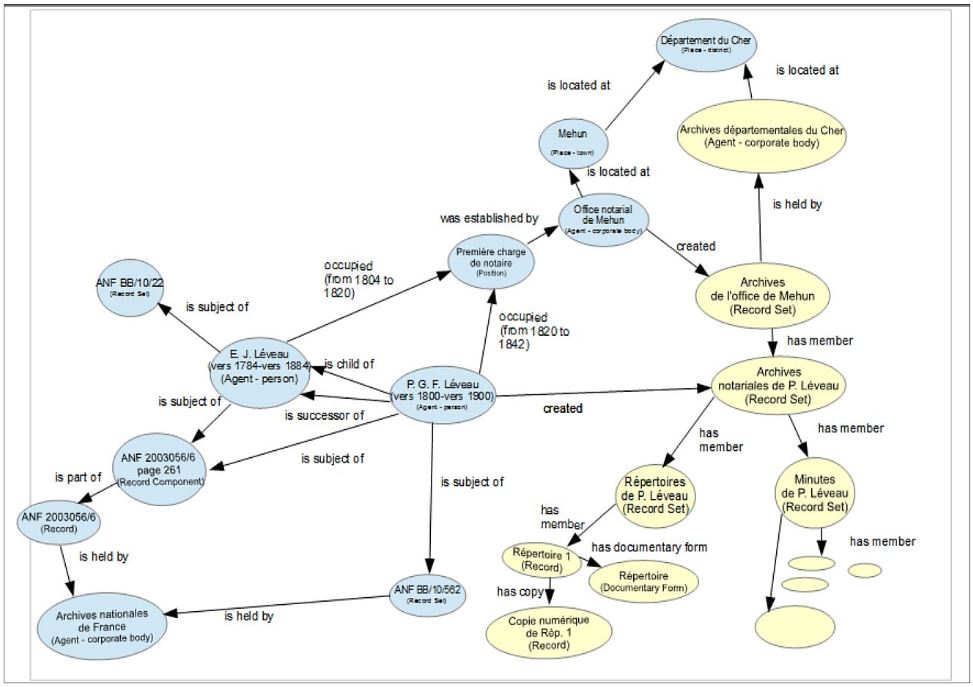

Pictured above is a piece of New York City history: the engineering log of WNYC’s first official broadcast 93 years ago. It began just before 9 p.m. on July 8, 1924 and lasted a mere three hours and 26 minutes. But in that time, bands played, singers sang, and various municipal figures extolled a new day in communications. Mayor John F. Hylan was one of those caught up in the moment. He leaned into a microphone and pronounced that radio now would bring news to the people of the city “in an interesting, delightful, and attractive form.”

Below are annotations for the entries in the engineer’s logbook shown above. Gaps were filled with newspaper and magazine accounts of the event. We’ve also provided context on some of the personalities cited.

WNYC’s reception room on July 8, 1924.

(Photo by Eugene de Salignac and courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives)

Some 2,000 invitations for the station opening had been sent out and reportedly more than 500 well wishers arrived to tour the new facilities on the 25th floor of the Municipal Building in the two hours prior to the broadcast. At this ‘open house’ the station’s first guests were welcomed to ‘a Spanish garden’ of ‘Moorish design’ with caged songbirds and colored lights adding an exotic ambience to the experience. You can read some of the newspaper accounts at this earlier archive blog piece: Romance of Radio.

Meanwhile, just one flight above, rooftop guests, with their drinks and hors d’oeuvres in hand, were chatting in the warm night air and looking west across the Hudson River at the Jersey lights and waiting anxiously for the public address speakers mounted around them to begin carrying the evening’s event.

8:54 P.M. On the air — no modulation. H. E. Hiller.

Harry E. Hiller in 1930.

Harry E. Hiller was at the controls when WNYC officially signed on the air. He was among WNYC’s original staff of 17 and hired for $2,700 a year. Hiller had come to WNYC from WBZ, which at the time was located in Springfield MA. Like WNYC’s Chief Announcer Tommy Cowan, Hiller was a radio pioneer, also having worked at WJZ in Newark, the New York metropolitan area’s first radio station.

8:58 Star Spangled Banner with Police Band and soprano – ACN.

‘Tommy’ Cowan as seen in 1938.

/WNYC Archive Collections)

Marian Fein is the soprano who sings the national anthem. ACN is the announcer Thomas H. Cowan. He is known to listeners only as “ACN” which stood for “Announcer-Cowan-New York” since, at that time, announcers and engineers did not reveal their real names on the air. WNYC’s founder Grover A. Whalen hired ‘Tommy’ just a week earlier to be WNYC’s Supervisor of Broadcasting at the princely sum of $3,000 a year and wrote, “the opportunity which is before you…is so great, so broad, and so limitless…” Cowan’s was the first voice heard when we went on the air July 8, 1924. Tommy was also the first announcer on the air in the New York metropolitan area when WJZ Newark started broadcasting in 1921. He announced the first World Series broadcast based on descriptions phoned into him from the game, as well as covering the June, 1924 Democratic National Convention from Madison Square Garden for WJZ.

9:02-9:09 Invocation, Blessing and Prayer

Catholic – Monsignor Charles A. Cassidy of Staten Island represented New York Archbishop, Patrick Joseph Cardinal Hayes.

Protestant – Reverend Dr. Charles H. Nauman represented Bishop William T. Manning.

Jewish – Rabbi Bernard Drachman (1861-1945) was the leader of Orthodox Judaism in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century.

9:16 Selection Police Band

The Police Band playing over WNYC from the roof of the Municipal Building in 1930.

(Eugene De Salignac/NYC Municipal Archives)

The Police Department Band was a staple of public events. At the time, the police, fire and the sanitation departments all had bands performing for the on-going assortment of ribbon-cutting and corner stone-laying ceremonies that frequently populated the municipal day book. However, this evening’s studio performance was no plum assignment. The new studios had just been painted a day earlier. Unfortunately, the paint sealed the special acoustic wallpaper so that sound bounced off of it rather than being absorbed. It was a fact that only became apparent as the broadcast was about to begin. At the last moment heavy drapes were hung on the walls and ceiling to dampen the sound but this also resulted in making the studio airtight. Needless to say, the performers were not pleased on that humid July evening.

The cover of the November 1924 Radio Stories magazine with the article by Hazel Ross, “The Birth of a New Station.”

(WNYC Archive Collections)

Writing in the pulp magazine Radio Stories, Hazel Ross described the scene: “With fifty or more, their instruments and music racks, jammed into that one small, heavily insulated room, the atmosphere took on the nature of a Turkish bath. Dripping drummers fled to the outer air in the very midst of martial selections…sweating saxophonists, casting fame and discretion to the winds, struggled out of the torture chamber, tearing open their shirts and gasping for air. Director Christie Bohnsack gave them time to mop their swimming brows, dosed them with ice-cold orange juice and then herded them back into their proper places with a masterly tactfulness…”

9:19 one moment please

Rodman Wanamaker

(Bain News Service/Library of Congress)

Although not noted in the log, newspaper accounts reported that at this point Rodman Wanamaker followed the police band and introduced Mayor Hylan. The department store magnate had headed up the original Board of Estimate committee appointed to study Whalen’s proposal of a city-owned and operated radio station. In April 1922 Mayor Hylan announced the committee at the opening of Wanamaker’s New York radio station WWZ.

Grover Whalen scrapbook clip of The Brooklyn Standard Union courtesy of NYC Municipal Archives.

Wanamaker’s introduction was interrupted by a furious summer thunderstorm that sent those listening on the rooftop racing for cover. The Brooklyn Standard Union’s front page the next day reported, “It supplied the real thrill of the evening. The crowd jammed the doorways, getting thoroughly drenched. One woman fainted, but was revived when taken downstairs to the offices of the Parole Commission, which immediately became the scene of animated but confused activity. An obliging youth named Mulligan, a city employee, put in an appearance with a handful of towels which the youngsters and the fairest of the visitors seized forthwith. Several young women discovered that their wet dresses were shrinking. Numerous hats were shrinking. Park Commissioner Edward T. O’Loughlin of Brooklyn flitted back and forth through the corridors drenched to the skin and anxiously looking for ‘Ma’ O’Loughlin, from whom he had been separated in the crush. Borough President Connolly of Queens, who had remained inside all of the time, nearly started a ‘riot’ by asking an acquaintance if ‘it had been raining outside.’ “

9:22 Mayor Hylan speaks

New York City Mayor John F. Hylan.

New York Police Department, Annual Report (1918), p.1. Held at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Lloyd Sealy Library Special Collections.

“Municipal information, formerly available only after perusal of reports, is now to be brought into one’s home in an interesting, delightful and attractive form. Facts, civic, social, commercial and industrial, will be marshaled and presented by those with their subjects well in hand. Talks on timely topics will also be broadcasted. Programs sufficiently diversified to meet all tastes with musical concerts, both vocal and instrumental, featured at all times, should make ‘tuning in’ on the Municipal Radio pleasant as well as profitable.

“Through the employment of this modern and very effective means of transmitting information, an aroused public interest in the municipal government may logically be expected to ensue upon a broader understanding, a clearer knowledge and a deeper appreciation of its functioning. And it follows, as night the day, that the more enlightened the citizenship, the better it becomes.” To read Mayor Hylan’s complete address go to: Hylan’s WNYC Speech. And, for more on the Hylan-WNYC backstory see: Mr. Hylan in the Air.

9:42 1/2 Ax Re: Vincent Lopez now in studio.

Dance band leader Vincent Lopez in the 1920s.

(Harold Stein/WNYC Archive Collections)

Tommy Cowan tells the listening audience that dance band leader Vincent Lopez (1895-1975) has just come into the studio. Vincent Lopez was a popular radio dance band leader. He began broadcasting a 90-minute program over WJZ Newark in November 1921. Lopez became one of the country’s most popular bandleaders through the 1940s, and his flamboyant style was said to have made an impression on Liberace. In 1941 Lopez and his orchestra launched a twenty year stint as the house band at Manhattan’s Taft Hotel.

9:43 “Novelette” Mr. H. Neumann pianist.

Herman Neuman at WNYC’s piano in 1927.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

Herman Neumann was hired as WNYC’s first music supervisor or music director and an assistant announcer at $2,700 per year. During WNYC’s earliest days, Neuman also acted as staff pianist. In 1929 he started The Masterwork Hour, radio’s first regular and later, longest running, program of recorded classical music. In a 1964 interview he recalled he would give as many as five piano recitals a day, announcing the selections himself from a standard volume called Masterpieces of Piano Music. Neuman said that many of the vocalists he accompanied were “song pluggers” who were dispatched to the station by music publishers to sing their latest songs on the air and encourage the sale of sheet music.

9:45 Mr. Lopez speaks

The orchestra of pianist Vincent Lopez in the early 1920s

(WNYC Archive Collections)

9:47- 10:27 Lopez and Orchestra Perform:

June Night, Limehouse Blues, Aida (modernized), Nola, Hottest Man in Town, Echoes of New York, Rubetown Frolic, What’ll I Do, Kitten on the Keys, piano solo, In a Ronderouz, I Can’t Get You, and a medley of George Cohan hits.

10:27 end of dance selections Thanks for calls and etc. Anx

Tommy Cowan back-announces the last musical selection and thanks all of the station’s well wishers for their calls.

Carbon microphone from 1920s

(WNYC Archive Collections)

10:29 Microphone crackles. Loose battery connection.

This was WNYC’s first official on-air technical difficulty. It was not, however, the only electronic snafu of the evening. The New York Times reported the following day that Mayor Hylan’s wife, “on an upper level, missed the Mayor’s speech when the amplifier failed to yield to his voice. It was found that the horn was rigged to a microphone whose adjustment had been overlooked so that it had not been ‘tuned in.’ “

10:30 Grover Whalen speaks. (Relay trips)

Grover A. Whalen.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

Grover A. Whalen was the outgoing Commissioner of Bridges, Plant and Structures, the parent agency of WNYC. It was Whalen’s strong belief that New York City should have its own radio station. He fought long and hard from 1922-1924 to make this idea a reality. He convinced the Board of Estimate to appropriate the necessary $50,000 to get the station on the air and battled against the emerging communications giants (AT&T, Westinghouse, General Electric and RCA), those he called “the radio trust,” to get a transmitter on his own terms. According to L. E. Brown in The Sun, Whalen “gave a brief outline of the difficulties encountered in securing the apparatus and installing it.”

10:35 President Connolly, Boro of Queens, speaks.

Queens Borough President Maurice E. Connolly in 1918.

(Press Illustrating Service, Inc./WNYC Archive Collections)

Maurice E. Connolly was significant because he had a sympathetic ear for technical innovations and sat on the city’s Board of Estimate and Apportionment, the governing body that appropriated money for capital projects. He was the first person Commissioner Grover Whalen approached in 1922 about the idea of a city radio station. As the Commissioner of the Department of Bridges, Plant and Structures, Whalen suggested to Connolly that he submit his (Whalen’s) proposal for a city radio station to the board. On March 17, 1922, Connolly recommended to the board that a committee study the proposal.

10:48 JA Lynch Boro President of Richmond speaks.

John A. Lynch is the Borough President of Staten Island and member of the Board of Estimate.

10:54 GAWhalen speaks. -ACN- HEHiller

Commissioner Grover Whalen returned to the microphone. It appears he was joined by announcer Tommy Cowan (ACN)..

10:59 short intermission

11:02 Ernest Jones Billy Hare & Vaughn DeLeath in a humourous dialogue.

Billy Jones and Ernest Hare on the air in 1923.

(NYWTS Collection/Library of Congress)

Vaughn DeLeath in the 1920s.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Jones and Hare were among of the most popular radio entertainers and recording artists of the time. Performing as The Happiness Boys, they were perhaps known best for their release on Victor Records Twisting the Dials, a comic vaudeville routine about that new media known as radio. Vaughn DeLeath was a a popular jazz singer and crooner in the 1920s earning the nicknames The Original Radio Girl and The First Lady of Radio. She was best known for her rendition of Are You Lonesome Tonight. However, it is curious that in reviewing the numerous newspaper and magazine articles about this event, not one mentions these leading radio performers or their routine.

11:12 Estelle Carey. Soprano

Estelle Carey in 1921.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

Estelle Carey (1890-1963) was a Canadian-born soprano who pursued a career in the United States in the 1920s performing in Detroit, Chicago and New York. The Canadian Encyclopedia writes that during a year long engagement at New York’s Strand Theater in 1923, her charming coloratura voice earned her the title, ‘The Little Brown Thrush of Broadway.’

11:13-11:23

Carey performed, The Winds in the South, Daddy, and Our Little Songs.

11:24 Six Brown Brothers – Saxophones.

The Six Brown Brown Brothers pictured on the sheet music cover of That Moaning Saxophone Rag in 1913.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

The Six Brown Brothers were a celebrity saxophone sextet. They were instrumental in popularizing the saxophone in the 1920s and often performed in clown costumes in both white and black face. They were William, Tom, Alec, Percy, Fred and Vern Brown. They began working in circuses and then minstrel and vaudeville shows. Bandleader Tom Brown claimed to have transformed the ‘siren of Satan’ to the apex of ‘the cool.’ The group’s records were the first discs of a saxophone ensemble in wide circulation.

11:26-11:37 The saxophone group performed Daughters of the American Revolution March, “Medley” and At Dawning.

11:38-11:50 Senor Alonzo, violinist

Senor Alonzo or Señor Alonzo remains a mystery although he performed Ave Maria with piano (probably Herman Neuman) and Spanish Dance.

11:52 Six Brown Brother Descriptive Selection

Clip from the “Journal” July 10, 1924.

(NYC Municipal Archives/Grover Whalen scrapbook)

11:59 Thanks for good wishes from WOR and others

The New York Telegram and Evening Mail reported the next day that hundreds of congratulatory messages had been received by telephone and telegram from persons who had listened in for the first time. Charles B. Poponoe, the director of station WJZ, also sent a huge bouquet of roses with a note that the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and New York’s pioneer station wished the first municipal station “all the luck in the world.”

July 9, 1924 A.M.

Ad for Huston Ray performing at the Majestic Theater in Elmira, New York in March 1925.

(Elmira Star Gazette)

12:01 “Elegie” transcription Huston Ray pianist

Huston Ray was the stage name for Ray Daghistan of Elmira, New York. The Post Star of Glen Falls, New York had this to say of Ray in August 1924: “Of all the people in the world who play the piano there is not over two score brilliant pianists and Huston Ray has the honor and distinction of being one of the small number. He is an accomplished musician, one whose technique and expression are faultless and with all the intimate personality that immediately puts him on good terms with his audience.” Ray was described as a graduate of the Winn School of Popular Music in Elmira, New York, where he also taught popular music and ragtime.

12:05-12:11 Ray performs Hungarian Rhapsody #6″ and What’ll I Do.

12:12 95th Ballot returns. Dem Conv.

Special Guest ticket to the 1924 DNC.at

WNYC went on the air in the final hours of the 1924 Democratic National Convention, held uptown at Madison Square Garden from June 24 to July 9. Grover Whalen’s original schedule had the station’s opening ceremonies on Friday, June 20 with regular broadcasts beginning the following Tuesday by covering the convention’s opening. However, Whalen did not announce the station’s completion and readiness for air until June 18 in a letter to Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover requesting a wavelength of 525 meters. Hoover responded by telegram late on June 21, issuing an experimental license with the call letters 2XBH. Still, Whalen needed a permanent Class B license and it appears political opposition was coming from WAOW in Omaha, which also operated at 525 meters. Meanwhile, The Sun wrote, “The Commissioner is ready to install direct wires from the studio in the Municipal Building to the Convention Hall at Madison Square Garden as soon as the permanent license is received.” WNYC got the Class B license, but not in time to cover the convention.

Newspaper headline about WNYC interference with DNC coverage.

(Grover Whalen scrapbook/NYC Municipal Archives)

Additionally, WNYC caused some upset among some convention listeners with its test broadcasts on July 5 and 7, as well as the official opening on the 8th. Newspapers reported that those with homemade receivers or less elaborate commercial sets were at a disadvantage in distinguishing between WNYC’s 525 meter wave length and WEAF’s 492 meter signal, leaving the listener with a jumble of the two. Hazel Ross wrote, “Just when the balloting was hottest, WNYC, gleefully taking her maiden dip in the ether, came in so strong that it was impossible to tune her out!”

FDR delivers the nominating speech for Alfred E. Smith at the 1924 DNC.

(FDR Library)

It took a record 103 ballots to nominate a Democratic presidential candidate in 1924. It was the longest continuously running convention in United States political history. John W. Davis, initially an outsider, eventually won the presidential nomination as a compromise candidate following a virtual war of attrition between front-runners William Gibbs McAdoo and Al Smith.

12:15 Auld Lang Song Chorus.

12:16 1/2 “Old Kentucky Home” “Home Sweet Home” Huston Ray pianist

12:17 1/2 Grover Whalen speaks

NYC Commissioner and WNYC head William Wirt Mills in 1924

(NYC Municipal Archives)

Grover Whalen provided concluding remarks for the evening’s festivities. He had resigned as the Commissioner of Plant and Structures several days earlier to work for Rodman Wanamaker. There were rumors something had come between him and Mayor Hylan. The commissioner, however, publicly insisted that the $10,000 a year he made just wasn’t enough to support his family. Mayor Hylan made him Honorary Radio Chief. The man now in charge of WNYC was Whalen’s deputy, William Wirt Mills.

12:20 Sign off

Newspaper accounts also mention two singers performing that evening not noted in the logbook: Soprano Muriel Tindal and a contralto named Rene Warwick. The British-born Tindal was at the Metropolitan Opera from 1921 to 1923. Despite research, information about Rene Warwick has not yet been located.

WNYC’s illuminated call letters, each nearly eight feet high, on the western face of the Municipal Building, July 8, 1924. The letters were flanked by glowing red cupolas.

(Eugene de Salignac/NYC Municipal Archives)

Special thanks to Alexandra Hilton, Archivist at the New York City Municipal Archives for her assistance.