WNYC Director Seymour N. Siegel in the 1950s.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

Public radio’s first program distribution network began in the fall of 1949. That’s when the director of New York’s municipal station WNYC, Seymour N. Siegel, made five sets of recordings of The New York Herald Tribune Forum and distributed them to twenty-two (National Association of Educational Broadcasters) NAEB member stations. Dubbed the ‘bicycle network,’ the new distribution system was thus formalized.[1] The plan was for tapes to move from east to west at one-week intervals. Once broadcast, a tape was mailed to the next station, and so on across the country. This arrangement required a significant amount of planning and scheduling by Terry Linder, WNYC’s network tape coordinator.

By February 1950, the NAEB via WNYC offered half-a-dozen educational stations copies of the Lowell Institute Cooperative Broadcasting Council[2] documentary series We Human Beings, dramatizing everyday problems that people face. A Long Life, a series of talks on medical topics came next, followed by Great Themes From the Great Hall, a series derived from WNYC broadcasts of the The Cooper Union Forum. These shows were soon joined by Freedom Sings, U.S. Army Band concerts recorded in Washington, D.C., BBC dramas and WNYC’s Music for the Connoisseur, hosted and produced by David Randolph. Cooper Union and The New York Herald Tribune underwrote some of the costs.

The idea for educational radio network programming with distribution by shortwave had been promoted by Mayor La Guardia and WNYC director Morris S. Novik as early as 1937. There had also been discussions of program delivery by transcription disc in 1939. But the real catalyst for network program distribution came out of the University of Illinois’ 1949 Allerton House Seminar on educational broadcasting. Before the meeting concluded, the gathering of thirty, mostly college-based, stations recommended “a central service for sharing programs, by tape or transcription, and a long-range plan for an educational network and a well-financed program producing center.”[3]

1950 U.S. postage stamp.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

Siegel had attended the seminar. He was also flush with postage stamps, as much as nine thousand dollars’ worth. This was a result of subscribers to the Masterwork Bulletin, the station’s program guide, paying for their annual twenty-cent subscriptions with stamps. The law required, however, that the stamps could only be used for postage. A light bulb appeared over Siegel’s head, and he realized he could use the stamps to mail tapes around the country and launch a distribution network.[4]

With Seymour Siegel’s leadership and a dedicated WNYC staff, the effort became a real exchange service supplying content to educational broadcasters across the country. But keeping the network going was a significant challenge. By mid-April Siegel wrote the following to NAEB President Richard Hull:

Trying to keep half-a-dozen Indian Clubs in the air at one time is not an easy job. The thing has taken tremendous resources in personnel and money. I have virtually exhausted our telegram code in the current budget, just trying to get some of our brethren a fast and firm answer. Mrs. Linder has been devoting almost all of her time trying to keep this Network functioning.[5]

Hull tried to remain encouraging.

I’m very much intrigued and pleased with the response the network is getting and I hope very soon that we have financing so can underwrite you a little more and you don’t have to bust your own neck and your staff to keep it going.[6]

By the second Allerton House gathering in July 1950, Siegel reported that WNYC was now supplying a network of thirty NAEB stations. NAEB President Hull wrote the organization’s officers and directors praising Siegel’s efforts.

The whole project marks a departure for American radio which is completely new and which Neal Morrison of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation hailed publicly at the Seminar as ‘the most stimulating development in radio on the North American continent.'[7]

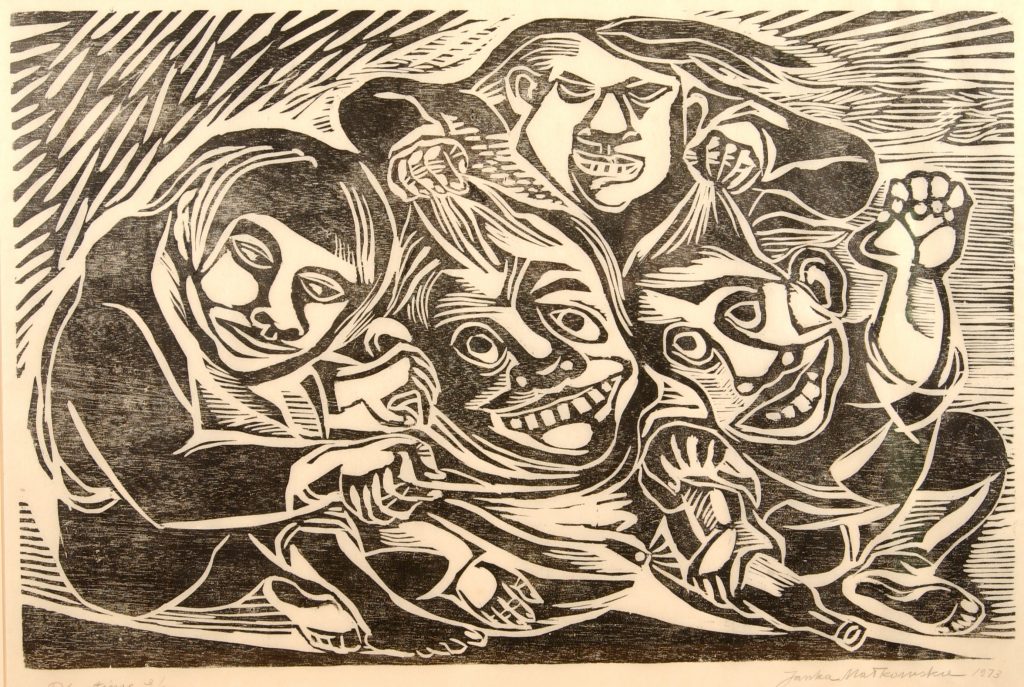

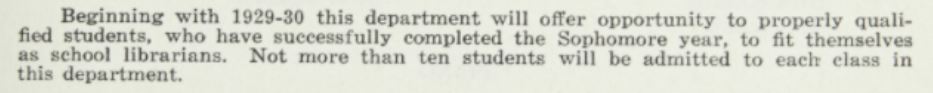

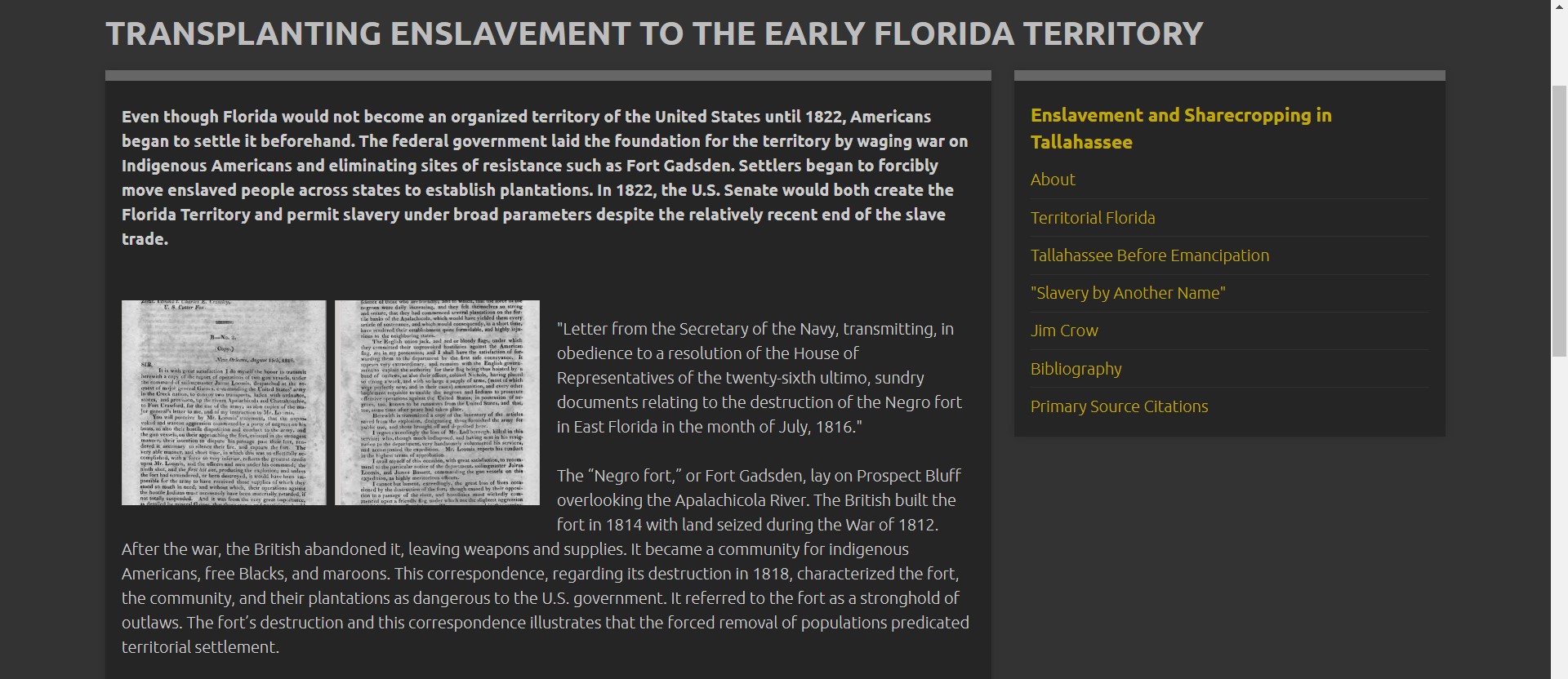

May 23, 1950, the NAEB distribution hub at WNYC makes page one of Radio Daily.

(NAEB Collection/Wisconsin Historical Society)

It was high praise, but Siegel made clear at the Allerton meeting that the whole operation at WNYC was a bit precarious. It depended largely on his efforts while he was on-call as a commander in the Navy reserves. He also noted criticism stemming from his role as the sole decision-maker for the network’s content: indeed, some ‘feathers got ruffled’ when an offered series got turned down. Additionally, some material quickly became dated due to the nature of the ‘bicycle’ distribution chain. These issues prompted NAEB president Hull to appoint an interim committee to review Siegel’s program selections as well as what the organization’s membership had to offer in the way of future shows.

The University of Illinois, Indiana University, and Purdue meanwhile offered to provide a permanent home for the program network.[8] However, Illinois stood out since it was willing to get funding for duplicating equipment, so that the same program could be released simultaneously to as many as fifty stations rather than the current ‘bicycle’ arrangement with tapes moving incrementally from station to station. In January 1951, the Division of Communications of the University of Illinois assumed custodianship of the network in Gregory Hall on the Urbana campus.

The tape network’s pivotal first year demonstrated need that outstripped WNYC’s ability to cover the resources required to make it work. Additionally, archive documents indicate that by the second Allerton conference, responsibility for the network had become a burden Sy Siegel was anxious to unload. Still, it was his willingness to ‘take the plunge’ that birthed the nation’s first public radio program network, based on the belief that radio used only for entertainment and the selling of merchandise was a serious waste of a significant national resource. For Siegel and members of the NAEB, radio broadcasting was a critical instrument for disseminating information, cultural experiences, opinions, and discussions, –and essential for solving contemporary problems.

______________________________________

[1] Hill, Harold, The National Association for Educational Broadcasters: A History, NAEB, Urbana, IL, October, 1954, pg. 42.

[2] The Lowell Institute Cooperative Broadcasting Council was an adult media education group whose members included, the Lowell Institute, Harvard University, Boston University, Tufts University, MIT, and Northeastern University,

[3] Howard, Jon R., Evolution of an educational radio program service network in the United States: a history of network 1914-1971, Masters Thesis, Kansas State University, 1987.

[4] Ibid, pg. 62. This postage story is based on a Corporation for Public Broadcasting oral history with former WNYC staffer Jerrold Sandler recorded in 1978. While the account may be true and a charming bit of public radio folklore, it appears the Siegel still had plenty of stamps left after nearly eight months of the NAEB tape network. Billboard reported in its August 12, 1950 edition he had $15,000 worth he wanted to unload. The piece was headlined: “Anybody Want to Buy 15G in Stamps? WNYC’s Got ‘Em.”

[5] Siegel, Seymour N., letter to Richard Hull, Director of WOI in Ames, Iowa, April 18, 1950, National Association of Educational Broadcasters Records at the Wisconsin Historical Society as part of “Unlocking the Airwaves: Revitalizing an Early Public and Educational Radio Collection.”

[6] Hull, Richard, letter to Seymour N. Siegel, May 24,1950. National Association of Educational Broadcasters Records at the Wisconsin Historical Society as part of “Unlocking the Airwaves: Revitalizing an Early Public and Educational Radio Collection.”

[7] Hull, Richard, Memorandum, “NAEB Network and Allerton House Meeting,” July 28, 1950, National Association of Educational Broadcasters Records at the Wisconsin Historical Society as part of “Unlocking the Airwaves: Revitalizing an Early Public and Educational Radio Collection.”

[8] Ibid.