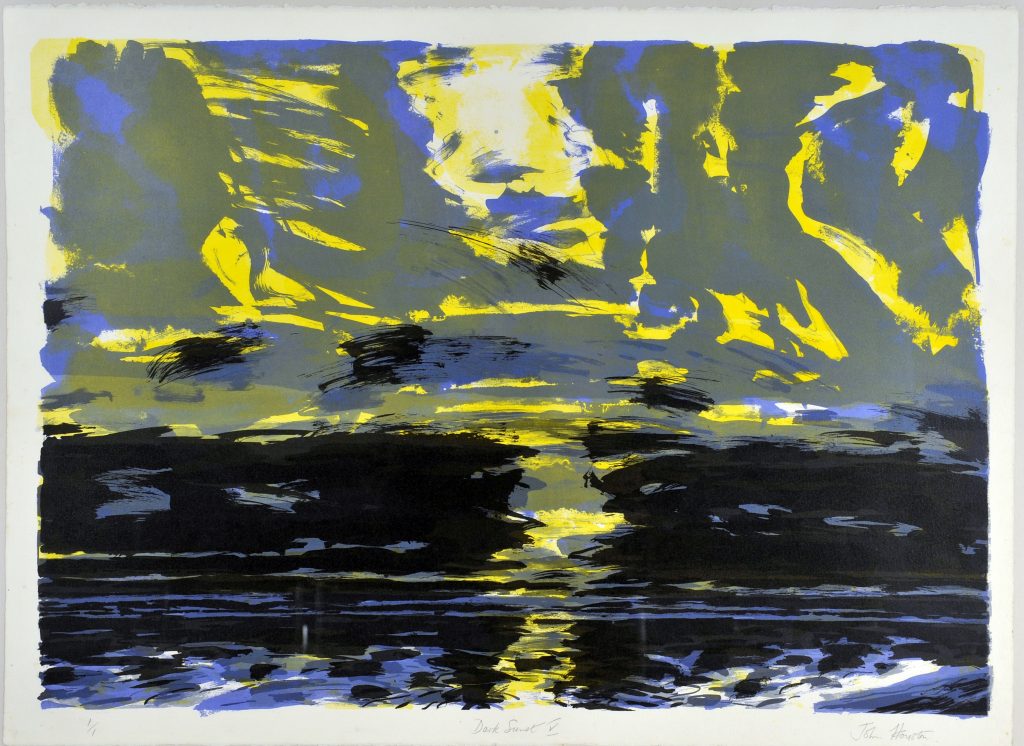

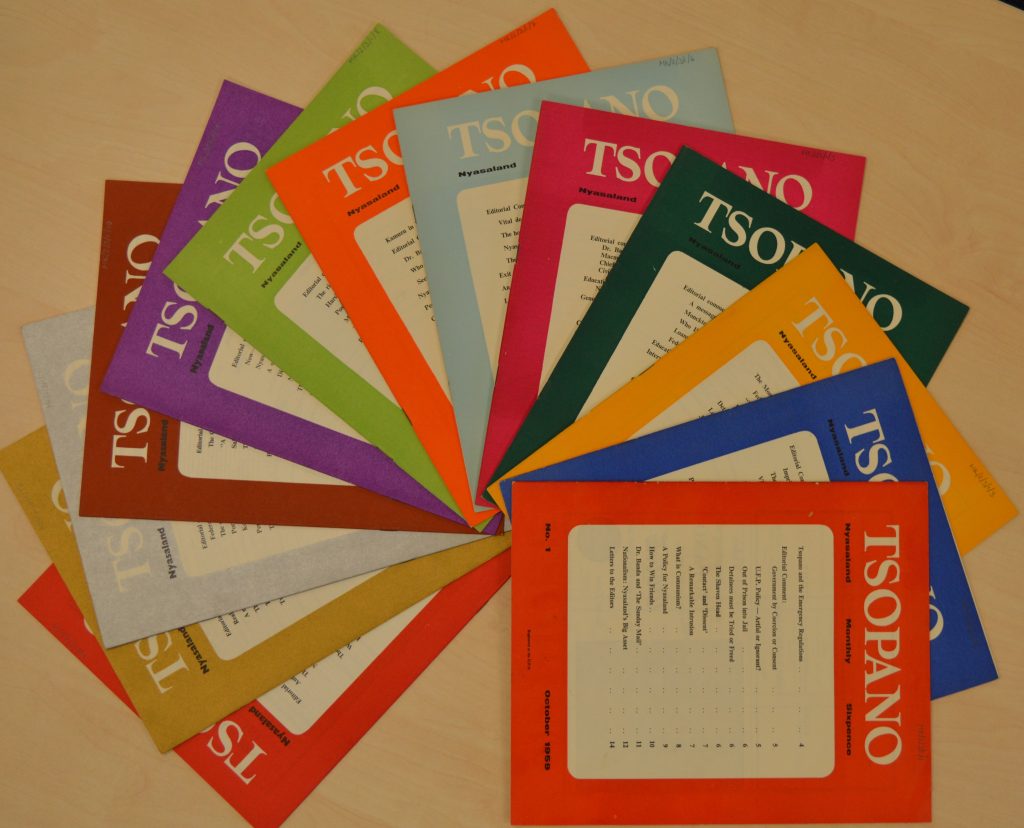

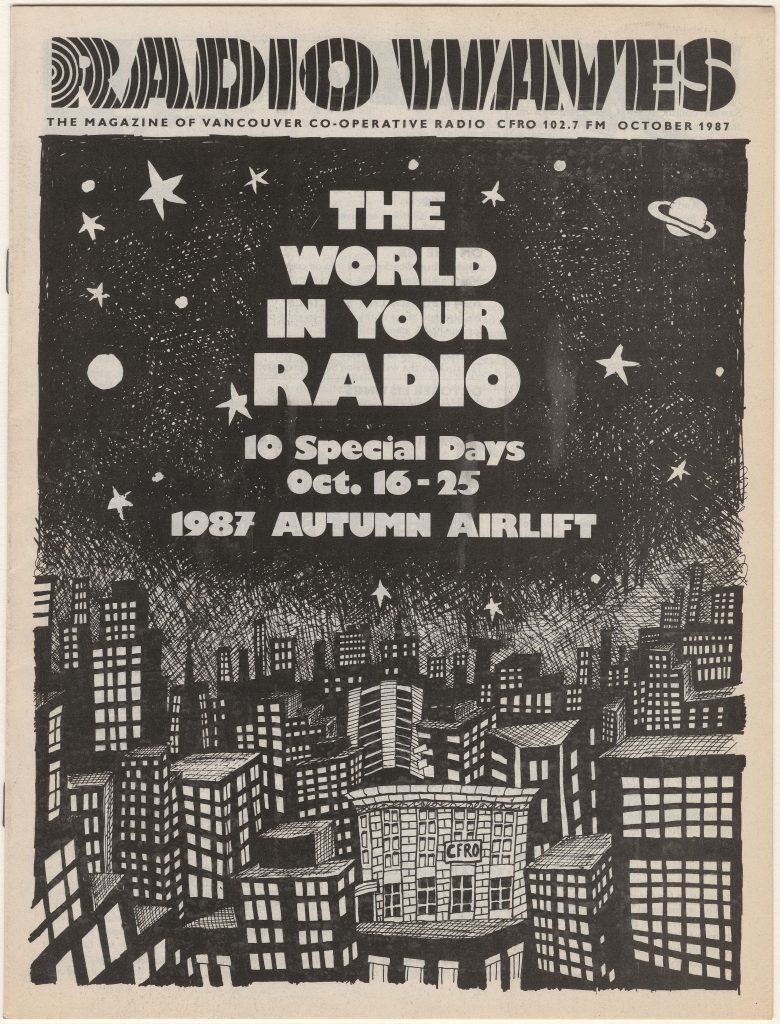

Mayor La Guardia at a WNYC mic in the 1930s.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

The notion of WNYC becoming the flagship station of a non-commercial network of cultural stations was first publicly articulated by Mayor La Guardia at the launching of the station’s new WPA-built transmitter facility in Greenpoint, Brooklyn on October 31, 1937. La Guardia envisioned a non-commercial/educational radio network connected via shortwave rather than expensive landlines leased by AT&T, but the FCC prohibited interstation communication by means other than wire when wire is available. At the ceremony La Guardia sharply criticized the FCC prohibition: “That is just as nonsensical and as unreasonable as to say that one isn’t permitted to fly from here to Chicago because there are railroads going from here to Chicago. Of course, all this is very good for the New York Telephone Company, but it is not so hot for us.” [1]

La Guardia’s plan for a non-commercial/educational radio network was based on the distribution of content via interstation shortwave rather than expensive landlines leased by AT&T. Agitated by the phone company’s distribution monopoly, the Mayor vowed to raise the matter again with the FCC and with Congress if necessary. FCC Commissioner George Henry Payne was expected to address those attending the WNYC transmitter dedication but called in sick. In a letter to program director Seymour N. Siegel, Payne indicated his support for such a cultural network. “There should be a chain of such non-commercial stations across the continent, free of pills and powders, laxatives, and Hollywood actors.”[2]

Less than a month later, Commissioner of Plant and Structures Frederick Kracke (whose agency oversaw WNYC) reported back to La Guardia that money was the only thing standing in the way of making WNYC into an international shortwave station. Such a facility, he noted, would promote goodwill with South America and supply the nation with news from the World’s Fair under construction at Flushing Meadows in Queens. Kracke indicated that as soon as funding was allocated, he would apply to the FCC for the proper permits.[3]

In the meantime, a world war for the hearts and minds of radio listeners was already underway via shortwave. Germany and Italy were regularly beaming broadcasts of fascist ideology to South America with the expectation of winning converts. Mayor La Guardia and then Station Director Morris Novik decided to counter this propaganda. On May 27, 1938, WNYC initiated a series of half-hour programs extending ‘goodwill greetings’ to South America through General Electric’s shortwave station (W3XAF) in Schenectady, New York. Each program ended with this statement:

This program comes from WNYC, New York City’s own station, where seven-and-a-half million people, who have come from all parts of the world, are now living in peace and enjoying the benefits of democracy.[4]

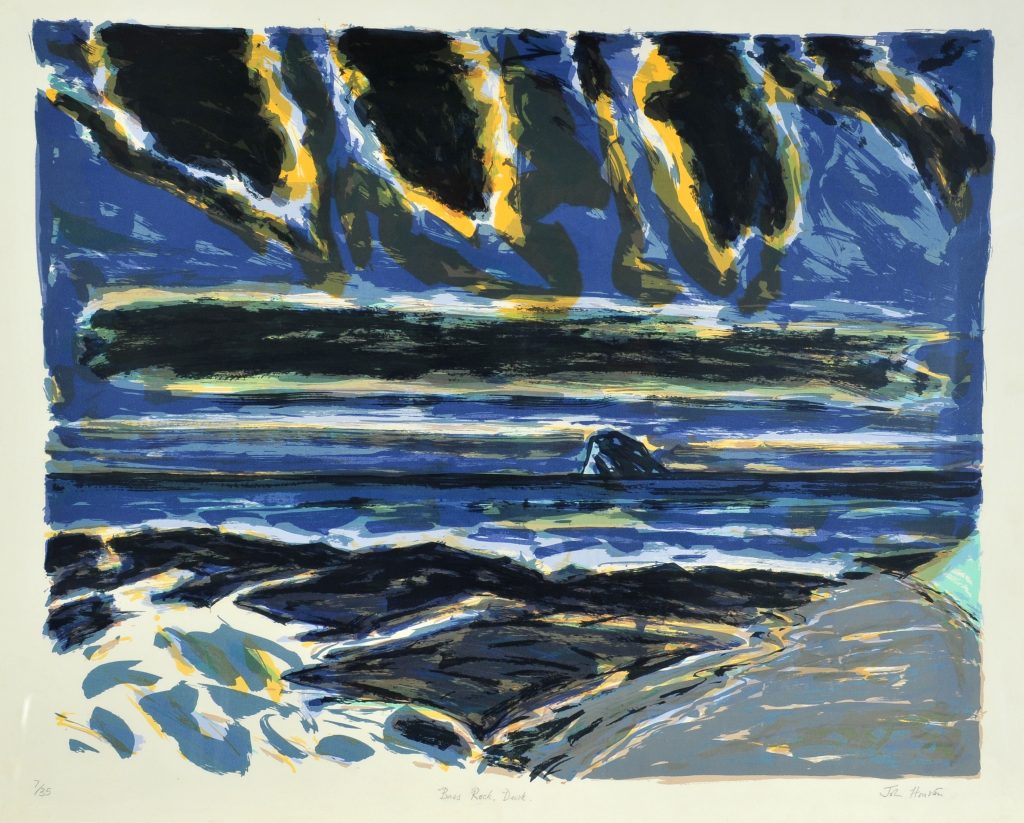

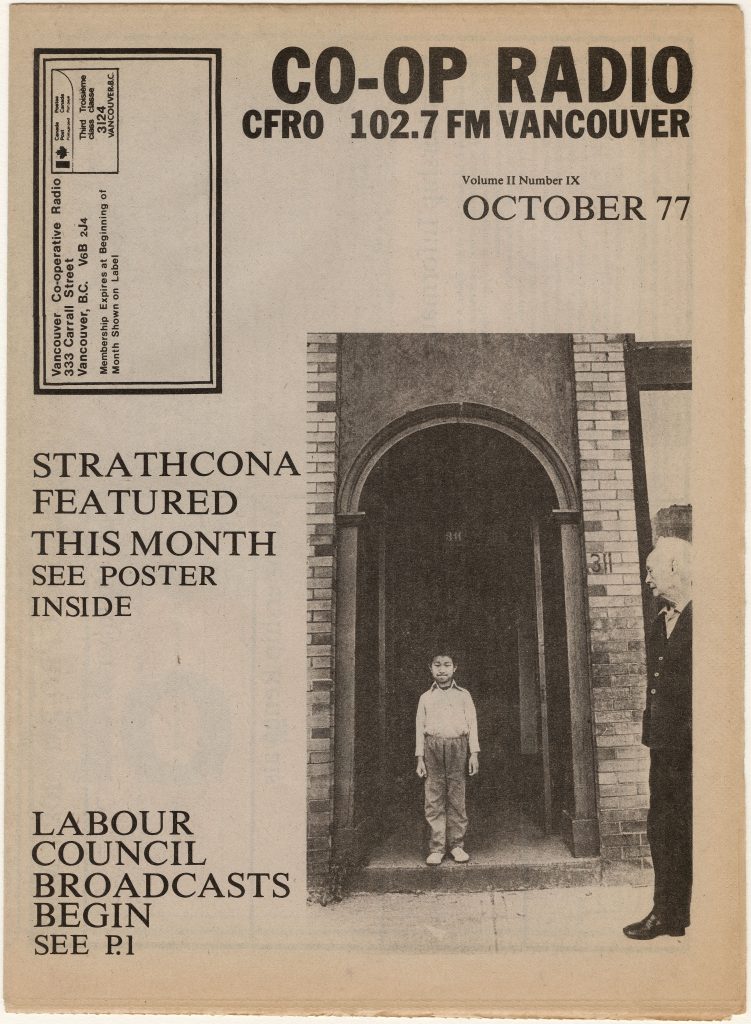

Walter S. Lemmon, founder and president of the World Wide Broadcasting Corporation.

(WNYC Archive Collections)

The relationship with GE was limited as WNYC turned toward the Boston-area station and fellow non-commercial facility, W1XAL. Also known as the World Wide Broadcasting Corporation (and later renamed WRUL), the international shortwave station was the brainchild of Walter S. Lemmon (1896-1967), a radio engineer and inventor who launched the facility to promote world understanding and education. In its formative years, the effort was bolstered by a series of grants from the Rockefeller Foundation, and its schedule read like that of a college or educational station, but with the BBC’s international focus. In May 1939, WNYC began sending its World’s Fair broadcasts of foreign pavilion openings to W1XAL.[5] By the fall of that year, other shows had been relayed to Boston, and the WNYC Masterwork Bulletin touted “W1XAL has shortwaved these programs ’round the world. In the future, W1XAL is going to take even more broadcasts from us.”[6]

The FCC appointed commissioners Norman S. Case, T.A.M. Craven, and George Henry Payne (a WNYC sympathizer), to consider the station’s case for the retransmission of W1XAL broadcasts received by shortwave rather than wire. Variety suggested a ‘liberalization’ of rules might be in the offing since others in the industry viewed the government regulator as little more than a stooge for the phone company.[7] Novik meanwhile signed up WNYC with the National Association of Educational Broadcasters (NAEB), a membership organization of some two dozen college stations, and then convinced them to endorse La Guardia’s position for the October hearing in Washington, D.C. With a ready network of stations, albeit small, WNYC could go before the FCC with some muscle.

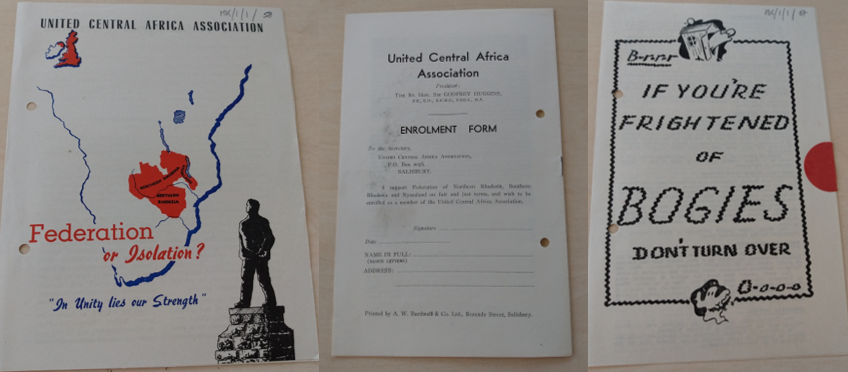

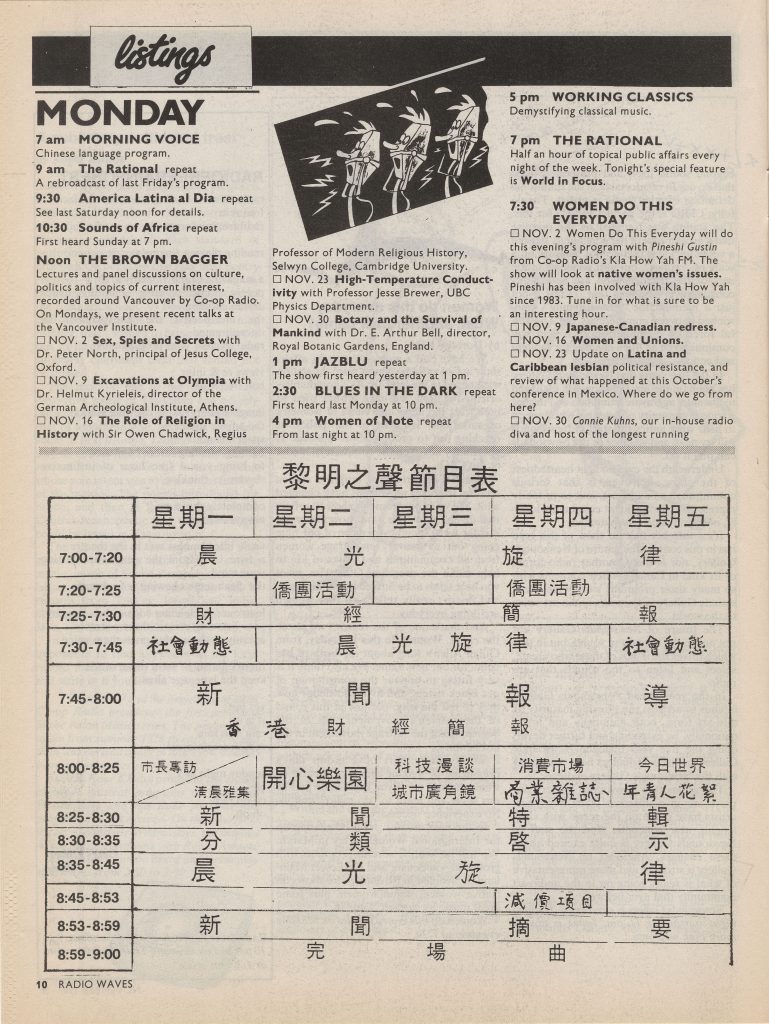

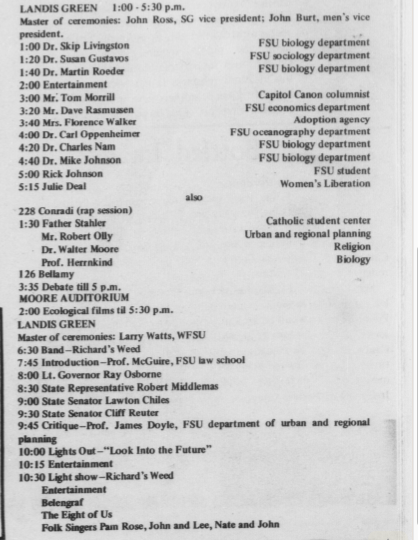

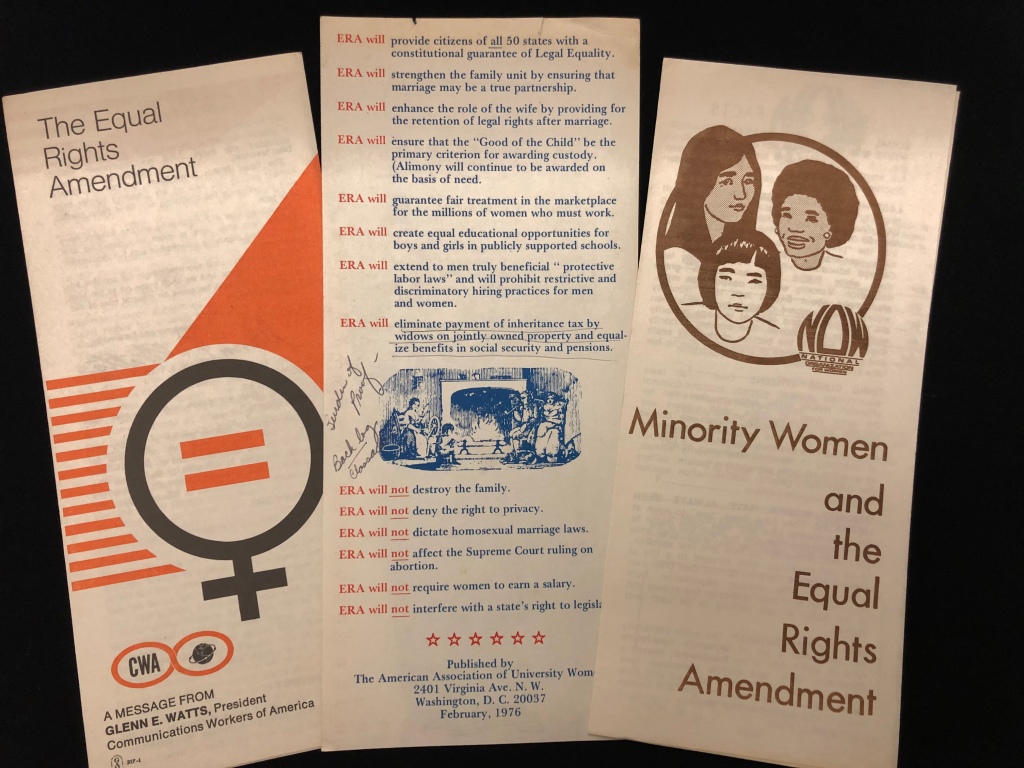

Excerpt of letter from the NAEB Executive Secretary Frank Schooley to Mayor La Guardia, September 6, 1939.

(NAEB Collection Wisconsin Historical Society)[8]

The FCC Hearing

On the day of the hearing, one city paper headlined the news as WNYC Air Link at Hand stating that “the torch of culture which New York’s municipally-owned radio station WNYC has held aloft may soon get the support of a national network” of 25 stations across the country.[9]

Walter Lemmon, Morris Novik, NAEB executive secretary Frank Schooley, Harvard professor William Y. Elliott, and executive secretary Howard S. Evans of the National Committee on Education by Radio joined Mayor La Guardia at the October 23, 1939 Washington, D.C. hearing. The Mayor summarized his position:

The application boils itself down to the one point –to permit us to pick up programs transmitted on what is known as the international band and to rebroadcast them on our wavelength. What we have in mind is to establish relations with the station at Harvard so that we may pick from its program such parts that would be educational and of interest to the people of the City of New York.

We are free to pick up a program on an international band if it originates in a foreign country, but not if it originates in our own country. We believe that if we were permitted to experiment with this station located at Harvard, it would not only be beneficial to us, but interesting as an experiment, and an encouragement to other non-commercial and municipal stations, or stations of educational institutions.

La Guardia also maintained that the United States would not have “an ideal radio condition” until there were an equal number of commercial and non-commercial stations. The Mayor argued, “these would serve as a protection to the people at a time when our country might starve for accurate information on some given point.”[10] Station director Novik testified that the issue actually went back to 1936, when WNYC wanted to broadcast material from the Harvard tercentenary programs but was prohibited from doing so because of the FCC regulations.

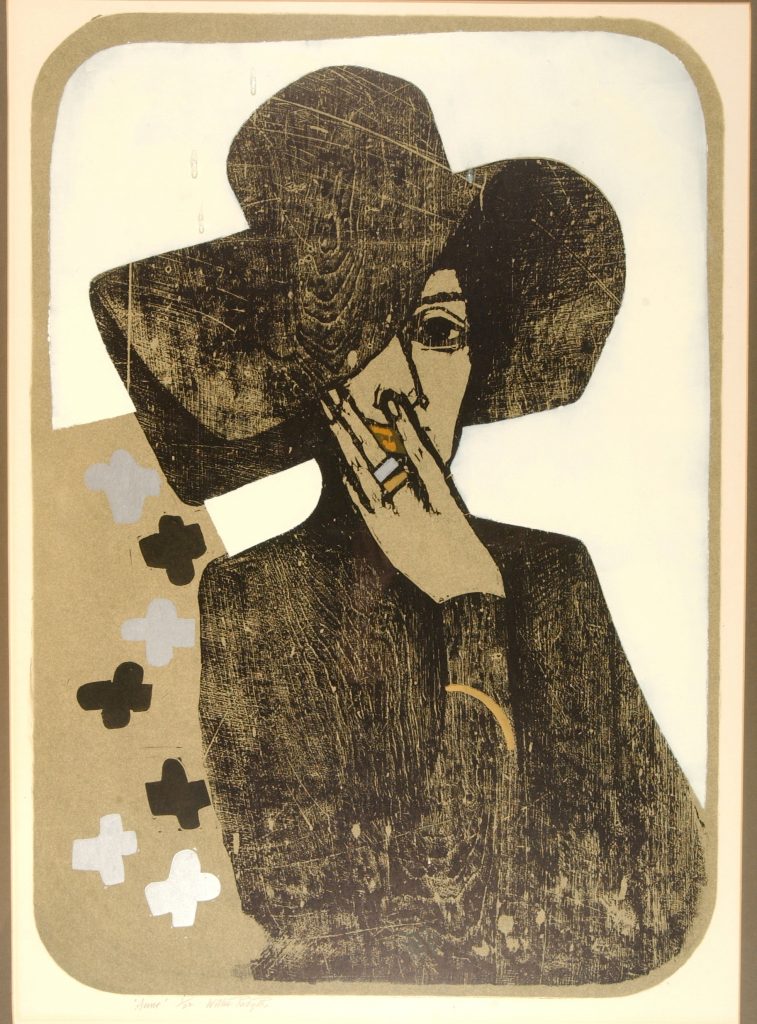

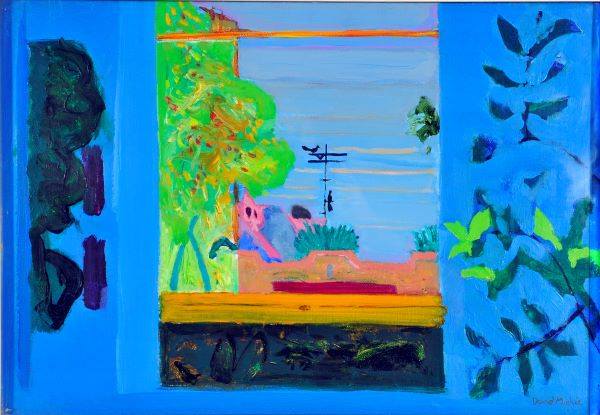

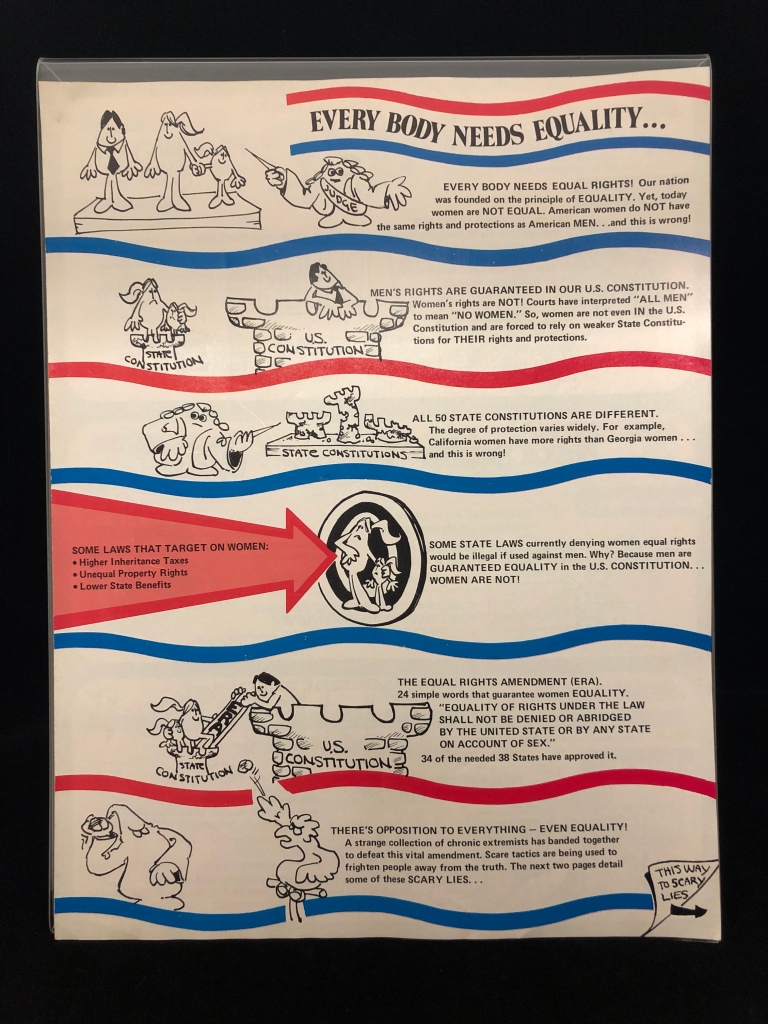

FCC Commissioners in 1937. Seated (l-r) Eugene Octave Sykes, Frank R. McNinch, Chair Paul Atlee Walker Standing (l-r) T.A.M. Craven, Thad H. Brown, Norman S. Case, and George Henry Payne.

(Library of Congress)

Andrew D. Ring, an FCC assistant chief engineer, and other agency officials testified that shortwave signals were impractical and unreliable as a rebroadcast or distribution service −and that if it were possible, it would be costly. [11] The engineer also argued that the rebroadcasting of this material could not be done without detracting from the operational efficiency of international broadcasters. Walter Lemmon countered that the use of a new and improved directional antenna at W1XAL and the similar installation at other stations, at a cost of a thousand dollars each, would solve the problem. Both engineers agreed that testing would be useful.[12]

While awaiting a decision from the FCC, WNYC had moved ahead with its shortwave transmitter, beginning test broadcasts from W2XVP at 26.1 megacycles. On April 4, 1940, the three FCC commissioners released their recommendation allowing for the non-commercial use of domestic shortwave broadcasts as long as three criteria were met: (1) the application could be for non-profit purposes only, (2) reception by wire placed an undue burden on the station, and (3) there were no legal barriers to carrying the material.[13] Less than a month later, WNYC filed for an FM license and began preparing for what was frequently billed as ‘static-less’ broadcasting.

Alas, La Guardia, and Novik’s vision of a ‘cultural network’ with WNYC as its flagship station and distribution by shortwave did not come to pass in the 1940s. The advent of FM, World War II home front efforts, and the leasing of WRUL to the Office of War Information for propaganda broadcasts changed everyone’s priorities. Radio listeners would have to wait until 1950 with the launch of NAEB’s ‘bicycle network’ of tape distribution, initiated by WNYC. The Pacifica Radio Network followed in the 1960s, followed by NPR’s network, of which WNYC is a part today.

_____________________________

Audio of Mayor La Guardia at the October 31, 1937 transmitter dedication ceremony at top is courtesy of The New York City Municipal Archives.

[1] WNYC Broadcast, October 31, 1937.

[2] “Mayor Denounces U.S. Radio Ruling,” The New York Times, November 1, 1937, pg. 3.

[3] “Kracke Tells Cost of Expanding WNYC,” The New York Times, November 15, 1937, pg. 26.

[4] The New York Journal American, May 26, 1938.

[5] “Young Clears Up N.Y. Radio’s Fog; Locals to Carry 160 Hours Weekly,” Variety, May 10, 1939, pg. 32.

[6] WNYC Masterwork Bulletin, October-November 1939, pg. 19.

[7] “More Liberal Pickup Rules Due; Industry Has Called Commish Stooge for Telephone Company,” Variety May 3, 1939 pg. 27

[8] Schooley, Frank E., Letter to Mayor F. H. La Guardia, September 8, 1939, NAEB Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society. Part of the University of Maryland’s Unlocking the Airwaves project.

[9] “WNYC Air Link at Hand,” The New York Journal American, October 23, 1939.

[10] Gilpin, Lewie V., “Feasibility of Wireless Chain is Contested at FCC Hearing,” Broadcasting, November 1, 1939, pg. 30.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “La Guardia Urges Lifting Radio Curb,” The New York Times, October 24, 1939, pg. 21.

[13] “Rebroadcast of International Stations is Recommended to FCC by Committee,” Broadcasting, April 15, 1940, pg. 52.